Salford University is offering media students 'live briefs' with the big broadcasters next door

The university is carving out a niche for itself as the front-runner for providing media-related courses for the next generation of students

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There aren't many UK universities that can offer their students work experience at some of the biggest media outlets in the country simply by taking a short walk along the corridor.

Nestling underneath the ITV studios that produce programmes such as the flagship current-affairs show Granada Reports, and just across the road from the BBC's new broadcasting headquarters, Salford University is carving out a niche for itself as the front-runner for providing media-related courses for the next generation of students.

The location of its media teaching and research in MediaCityUK, the 200-acre development on the former site of Manchester Docks, means that Salford University can not only provide its media students with some of the best facilities in the world but also offer them a location that is cheek by jowl with the major broadcasters

As a result, Annabelle Waller, the director of media and broadcasting for the university, notes that the university is beginning to attract a range of international students for its courses. "I think they are aware that in coming here they're a 10-second walk from some of the biggest media players in the country. It feels successful."

The message hasn't been lost on UK students, either. Beth Hewitt, director of admissions, says that many young people have travelled to Salford from around the country to see what the university has to offer. "There were a lot who travelled from quite a long way away – London, Devon, Portsmouth," she says. "I think the message is getting out there."

Since the university's decision to move into MediaCityUK in 2011, it has seen a major expansion in the number of students opting for media and broadcasting courses. But it's a build-up that hasn't happened overnight. "You can't just say that you're offering this experience and then expect 3,000 students to turn up," says Hewitt. "You have to build up gradually."

Salford is an embodiment of the dream that the former universities minister David Willetts had for the higher education sector when he was in office. He always predicted that a number of universities would develop a speciality in one or two areas and become internationally renowned for these subjects.

"There is a lot of creativity here," says Martin Hall, the university's vice-chancellor, "and what we're about is driving up aspiration."

He describes Salford as "gritty but authentic". "If you want a Loughborough experience [the university is renowned for its sporting excellence], then go to Loughborough," he says.

But he believes today's students are attracted by factors other than a glittering campus. "Things such as employability are really important to today's students now they are paying £9,000 a year. The post-crash generation [those who have started their higher-education courses since 2008] don't have a sense that they have been cheated or denied anything. They're more entrepreneurial. Owning a house is now so remote to them, they don't even think about it, but there are not a whole lot of young people thinking, 'I'm not going to get a job.'

"I think the economy is beginning to take off now, and we're going to see some significant development and it is going to look very different in the next five years."

Salford is playing its part in preparing the local community for the future by sponsoring one of the new breed of University Technical Colleges (UTC), which help prepare those aged between 14 and 19 for the world of work (co-sponsors will be the local arts organisation Lowry Theatre Centre and the educational charity the Aldridge Foundation, which already runs a network of academies).

The UTC will be opening in MediaCityUK, too, and will start taking students next September. "It will specialise in the media and we'll be working very closely with those involved in MediaCityUK," says Professor Hall. "This is the biggest concentration of high-performance digital centres in Europe."

The UTC fits in with the university's avowed aim of developing the aspirations of local young people, offering them the opportunity to specialise in training for the media before moving on to the university or taking up an apprenticeship.

It would be wrong to paint a picture of Salford as specialising in media programmes to the exclusion of all else. It has also developed an expertise in devising higher-education programmes of study for the NHS.

While Salford's links with MediaCityUK are fast building its reputation among young people seeking careers in the media, in the past it has been identified with providing courses in as midwifery and other subjects related to health care. Its most recent innovation has been the setting up of a Salford Institute of Dementia – the only one of its kind in England – which is trying to promote a more positive picture of the medical condition.

Professor Maggie Pearson, who is dean of the University's College of Health and Social Care and is responsible for the institute, points out that there are more than 40,000 people in the UK diagnosed with dementia under the age of 65 (out of 813,827 who have the disease). "It's not a question of giving them all the same treatment," she adds. "You don't want to give a person of 52 the same treatment as someone who is 90 and may require more help.

"Some 25 per cent of people with dementia live on their own. You don't want to fill them with a 'despair' model that will become a self-fulfilling prophesy. You want to give them hope instead," says Professor Pearson.

Indeed, the institute shies away from talking about dementia as a problem or about people suffering from dementia but devotes research to working out the best ways of supporting sufferers instead. It will also be launching an MSc that will look at care-focused and design-focused ways of providing aid to people. The first students for the MSc will be recruited in January.

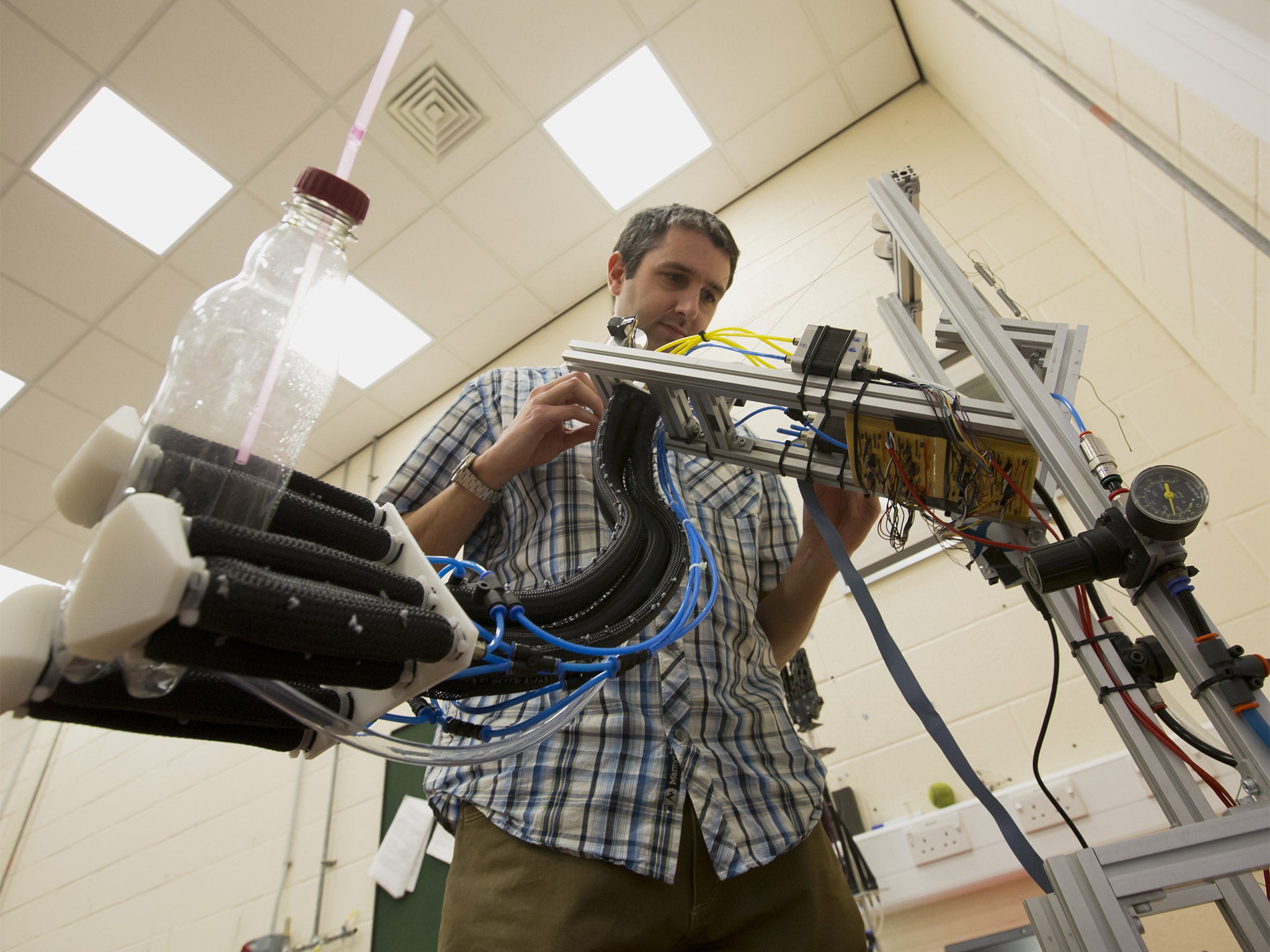

One of the more unusual innovations under research at the institute is designing robots that can help to feed people. Those with dementia quite often forget to eat or take their medicine and the soft-tissue robot can grasp a bottle in its arms and provide food to a person who has forgotten to eat.

Another use of the robot – which could be used to help a range of elderly patients with a wide variety of ailments – is to help ease a patient with limited mobility out of a chair. The device can sense when a person wants to get up and gently raise the chair to help them.

Professor Pearson, who was director of education and training for the NHS before she came to Salford, is anxious to develop a dementia-friendly environment among local businesses and public services. Simple things – such as having the ladies' sign for the toilets too low – can be a difficult for people with dementia, as can be symbols denoting men and women.

Through its promotion of its expertise, Salford is carving out a distinct niche for itself in higher education. However, another way you can see the strides it has made is by looking at the people on the sofa providing expert analysis for shows such as BBC Breakfast.

Since the BBC moved the flagship programme to Salford from its previous base in west London, the usual academics from the London colleges are increasingly being displaced by experts from Salford University.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments