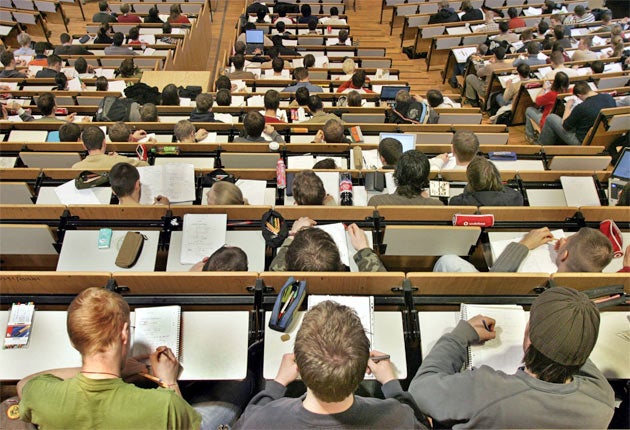

Are students getting what they pay for?

Paying higher fees means students will demand more value for money. With complaints already rising, Jonathan Brown looks at how universities are coping with being called to account

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When she asked to transfer courses to take graphic design and marketing, communications undergraduate Rana (not her real name) was told she would have to start her university career all over again. Without a business studies A-level it was a question of going back to year one, she was warned.

Later on in the course, however, she encountered three other students who – it seemed – had been allowed to make the transfer without the necessary qualifications. It seemed completely unfair.

Three years later, despite having raised the issue with her programme advisor and head of faculty and consulting a solicitor, she is still awaiting a response. Needless to say she feels very let down. "None of the staff have had the courtesy to look into this problem," she says.

"The university has cost me three unnecessary years of tuition fees and time wasted on separate studies. I am now having to pay from my pocket, as the student finance office has a limit for financing degrees per person."

Students to date have been deeply reluctant to take on their universities when they have a problem, and even more afraid to speak out, fearful that it might have an impact on their future career prospects. But with the majority of universities now confirmed to be hiking their fees to the maximum £9,000 a year, student expectations are set to rise, too. And with post-college debts likely to top £30,000 or even £40,000 and 20 per cent of graduates out of work – the highest figure since the 1990s – more voices like Rana's are likely to be heard.

There was a taste of things to come last month, with the publication of the annual report of the Office of the Independent Adjudicator (OIA), the body that was set up to review student complaints that can't be settled within a university's own internal procedures.

In 2010 the number of disputes it was asked to deal with rose 33 per cent to 1,341 – a figure that has doubled in recent years. At present it is estimated that the OIA is only called to look at one in every seven complaints, with the remainder being dealt with by the institution concerned.

But to illustrate the point that things are changing, the OIA took the unparalleled step in its annual report of publishing the names of two universities that it felt were non-compliant with its rules.

Although insisting that identifying the University of Westminster and University of Southampton was not part of a process of "naming and shaming", it was clearly a shot across the bows of those seats of learning that think they might be able to ignore the process in the future.

OIA chief executive Rob Behrens believes the amount of complaints will continue to rise as higher fees start to bite and students begin to assert their rights – even if the total number of files crossing his desk remains a tiny fraction of the current student body.

Last year, the number of complaints represented just 0.05 per cent of the 2.2m enrolled in higher education. Only 20 per cent of the complaints received were eventually ruled justified or partly justified.

"The debate about tuition fees and students becoming consumers is influencing students and there is great awareness among students about what their positions are," says Mr Behrens. "The labour market is still very difficult for graduates to get employment and they will use every opportunity to get the best out of their university experience," he adds.

The issue with Southampton focused on three cases, including one in which the university continued to object to compensating a student four months after their complaint about their placement was upheld by the OIA. Westminster, meanwhile, faced public censure over its handling of a complaint involving a disabled student and another over the marking of an exam paper.

Both universities are now working more closely with the OIA following the involvement of the respective vice chancellors in the case.

It is something that institutions will have to get used to, explains Mr Behrens, who in his previous job was complaints commissioner for the Bar Council.

Next year, while the identities of the complainants will remain confidential, the names of the institutions involved as well as a summary of the facts of the case are to be published, thereby offering potentially key information for any future applicants to universities. And while the OIA does not have the power to punish or fine, institutions will have to start paying more for the pleasure of being part of a complaints system in England and Wales that was enshrined in law under the 2004 Higher Education Act (at present private universities are exempt from the process, although two are in the process of signing up voluntarily).

Mr Behrens is due to consult with the sector this year, but it looks likely that universities will be required to pay a case fee so those institutions that generate the highest number of complaints will have to stump up the most. He believes the new process will be both "transparent" and "engender trust". "We have to incentivise universities to follow their own complaints procedures. Universities have nothing to fear from that because their record is good."

However, Mr Behrens believes they can still do more. One of the most common gripes is that students are not kept properly informed and the process of dealing with the original issue and appeal takes much too long – on average about six months. "That is not about the outcome but good customer service, that you take your complainants with you," he says.

By and large universities recognise the need to increase transparency, and view their relationship with the OIA as "constructive". But vice chancellors are urging that any future "complaints league table" should include contextual information such as the statistical significance of the number, the student profile and the subject mix.

Professor Sir Steve Smith, president of Universities UK and vice chancellor of Exeter University, says following the OIA's report in June: "Universities are not complacent and there will be challenges ahead. Universities will have to be increasingly clear about what they offer students. That is, a high-quality product and skills and experiences that will directly benefit the student." He says students are becoming increasingly aware of the OIA and demanding over how they are treated.

But Liam Burns, the new president of the National Union of Students, believes a three-month time limit should be set on resolving complaints, while institutions should also introduce a campus ombudsman in order to mediate disputes at a lower level. "Dealing with disputes with universities can be a distressing and time-consuming process for students that can have negative consequences on their education," Mr Burns says.

"Where universities are currently not good enough at dealing with complaints, both the institution and the student have to waste time and effort, ultimately resulting in poorer graduates and a waste of public money."

Meanwhile, Rana advises future students to shop around. "You feel a lot of pressure to do a degree and you don't want to let anyone down, so I took the first offer I could. However, since then I've learnt that there are more cons than pros," she says.

What should I do if I have a complaint?

The first stop is the university's complaints and appeals procedures. These vary from institution to institution and the vast majority of issues are resolved internally. Your university should publish details of its complaints procedure either on its website or in its handbook. If in doubt, consult your student union.

What happens if my university rejects my complaint?

You will be notified of the decision via a "completion of procedures" letter. This will advise you of your right to refer the matter to the OIA. You must get in touch within three months of receiving this letter.

Where can I find out more information about the OIA?

Look at its website at oiahe.org.uk.

Can I complain about my degree classification?

No. The OIA will examine your case only if there has been a procedural problem. Matters of academic judgement are for the university.

My problem arises from my work placement. Can I still complain?

Yes. Your university has an obligation to make sure you are fairly treated during this time.

What other safeguards are there?

The Government wants all universities to publish a student charter which will remind students of their rights and responsibilities.

Disputed facts

In 2010 the number of disputes dealt with by the Office of the Independent Adjudicator (OIA) rose by 33 per cent to 1,341. Of these, 169 complaints were ruled justified or partly justified.

Of the eligible complaints, 53 per cent were deemed unjustified.

Last year, complainants received £173,959 in compensation. The largest individual payout was £15,000.

This number is expected to rise as students are required to pay higher tuition fees.

Post-graduate students and those over the age of 25 are statistically the most likely to lodge complaints.

Studies related to law, medicine and business and administration are the most likely to elicit complaints.

Six out of seven student complaints are dealt with internally by the individual universities.

Southampton and Westminster universities were found to have breached complaints guidelines.

Institutions that fall foul of OIA rules will be named in 2011.

There are currently 2.2m enrolled higher education students in England and Wales.

The average time to resolve a complaint is six months. The National Union of Students wants this to be reduced to three months.

Of the 123 universities in England, 80 are to set the maximum tuition fee of £9,000 a year.

One in five university graduates is currently unemployed.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments