Pupil exclusions soar as Black Caribbean and Traveller students kicked out of school at higher rates

Study warns racism and teacher bias could be in part to blame for higher rates of exclusions among children from some ethnic minority groups

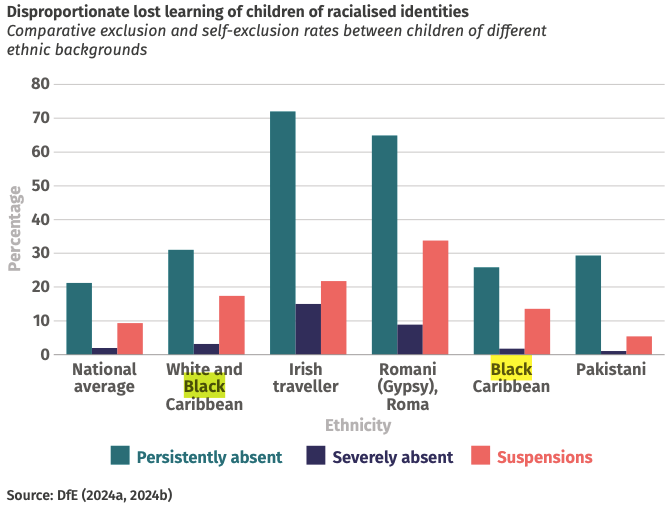

Pupils from some ethnic minority backgrounds are up to four times as likely to get kicked out of mainstream schools as exclusion rates surge, a new study suggests.

Black Caribbean students and pupils of dual Black and white heritage are twice as likely to be moved to an alternative provision such as Pupil Referal Units (PRUs), while Romani/Gypsy, Roma and Irish Traveller are four times as likely to experience these outcomes.

The new research, by the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR) and education charity The Difference, has prompted campaigners to warn racism and teacher bias may be behind racial disparities in exclusion figues.

Suspensions and exclusions across all schools and all year groups in England increased by almost a quarter last year compared to the previous year.

Efua Poku-Amanfo, IPPR research fellow, said: “Lost learning is contributing to racial injustice as children from some ethnic minority backgrounds (Black Caribbean and Romani (Gypsy) Roma, and Irish Traveller) are disproportionately being excluded.

“Many of these students have expressed that they experience racism at school which can impact their feelings of safety and belonging.

“As a result, these young people are more likely to be placed in alternative provision (AP) away from mainstream schools and at higher risk of poor attainment and youth violence.”

Citing research by Jahnine Davis, a leading UK expert in adultification bias in child protection and safeguarding, the study argues that an underestimation of racism experienced by ethnic minority children outside and within school, combined with this bias, partly explains how their vulnerability may go under-recognised.

Consequently, behaviour stemming from these vulnerabilities may be read as purely disruptive and maliciously-motivated – and met with sanctions rather than investigation.

Wider research suggests that teachers’ perceptions of who is a “good learner” in classrooms are shaped by gender, race and class, which in turn shapes which pupils are perceived to be less able to learn.

This comes as the rate of Black Caribbean girls being kicked out of schools has tripled within the past year.

The report also warned many widely used estimations of exclusions and absences have failed to capture the full picture of children losing learning nationally, finding that the most vulnerable children are most likely to miss out on their education.

Poorer children, children known to social services, those with school-identified special educational needs (SEN) and/or mental health issues, as well as children from ethnic minority backgrounds, disproportionately experience missed learning.

Some 90 per cent of excluded pupils do not achieve a pass in GCSE Maths or English, while over half of children not entered for maths and English GCSEs in alternative provision schools while fewer than five per cent gain a standard pass.

A Department for Education spokesperson said: “The rising number of school suspensions and permanent exclusions are shocking, and show the massive scale of disruptive behaviour that has developed in schools across the country in recent years, harming the life chances of children.

“We are determined to get to grips with the causes of poor behaviour: we’ve already committed to providing access to specialist mental health professionals in every school, introducing free breakfast clubs in every primary school, and ensuring earlier intervention in mainstream schools for pupils with special needs.

“But we know poor behaviour can also be rooted in wider issues, which is why the Government is developing an ambitious strategy to reduce child poverty led by a task force co-chaired by the Education Secretary so that we can break down the barriers to opportunity.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks