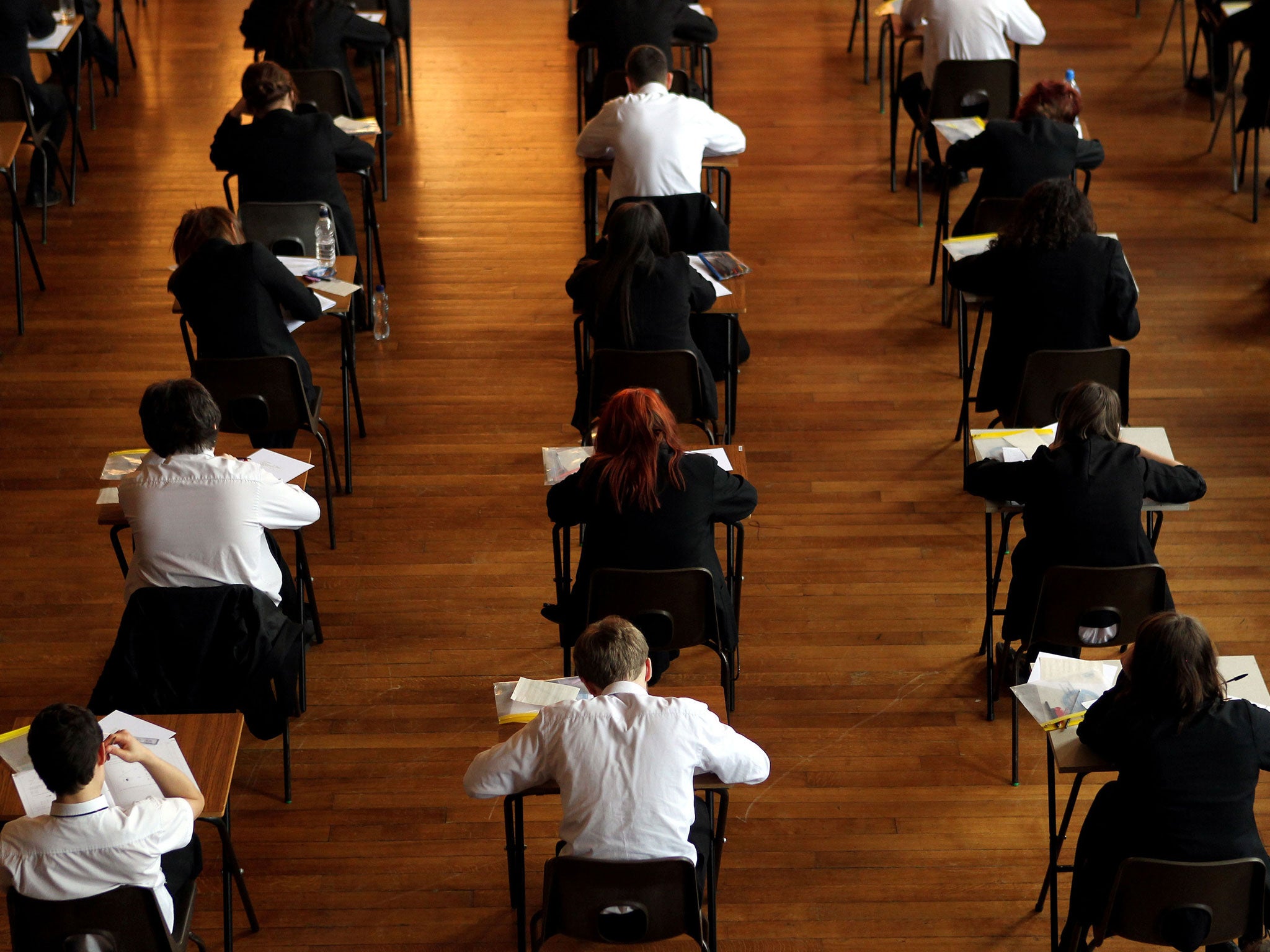

Half of clever students from poor backgrounds fail to secure top GCSE grades, study says

'It is essential that we address this wasted talent'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Almost half of clever but disadvantaged students fail to secure the top GCSE grades, according to a new study from social mobility charity, The Sutton Trust.

Bright pupils from poorer backgrounds are more likely to fall behind their richer classmates by the time they get to Year 11, the report warned.

Action needs to be taken to combat this “wasted talent” and to ensure disadvantaged students who performed well in primary school are able to fulfil their potential later on in school, it said.

Poorer students are three times less likely to be in the top 10 per cent of students in English and maths at the end of primary school - with just four per cent of disadvantaged 11-year-olds considered to be high attainers at this age.

This compared with 13 per cent of non-disadvantaged children.

At GCSE, just 52 per cent of the disadvantaged high achievers at primary school secure at least five A*-A grades in England, compared with 72 per cent of their wealthier, equally clever, peers.

It means that if high-achieving disadvantaged pupils performed as well as high-achieving students overall, an extra 1,000 poor students would gain at least five A*-A grades each year, the study said.

The research also that disadvantaged high-attaining pupils are half as likely as high-achievers overall to enter a grammar school, concluding that in grammars, one in 17 of all high-attainers are from poorer backgrounds, compared with one in eight in comprehensive schools.

The Sutton Trust's founder Sir Peter Lampl, said: "Too many talented young people from less well-off backgrounds gradually fall behind during their school career, as the barriers they face take a toll. It is therefore essential that we address this wasted talent."

The study, which comes just weeks before teenagers learn their GCSE results, calls for Ofsted inspections to consider a school's support for disadvantaged bright students and for GCSE scores for poor pupils with high prior attainment to be published in annual league tables.

Sir Peter added: "It is worrying to see that disadvantaged pupils with the potential for high achievement are falling behind their more advantaged peers. All pupils should be given the chance to realise their potential regardless of their background. We need better evidence of how to improve the attainment of disadvantaged highly able students. Schools should be monitored and incentivised to do this."

Geoff Barton, general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders (ASCL), said: “We need to do more as a society to help young people from disadvantaged backgrounds to achieve their potential.

“Many schools are doing a superb job every day to give these young people the start in life they deserve. But these students can face very difficult challenges beyond the school gates and often live in communities which have been drained of hope by decades of insecure and poorly paid work.

He added: “Schools in these areas also face the toughest systemic challenges, particularly in terms of recruiting teachers and leaders. We need a joined-up approach with social and economic policies which restore hope to these communities alongside more support for their schools. We are not, however, convinced that any of this will be driven by further changes to accountability measures.”

With additional reporting by PA

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments