'Educate girls to stop population soaring'

The longer girls stay at school, the fewer children they have, professor says

The explosive growth in the global population could be curbed significantly if teenage girls in the developing world were given the opportunity of completing a secondary school education, says a leading expert in human numbers.

Putting girls in developing countries through secondary school is one of the single most important factors that causes them to have fewer babies in later life, said Joel Cohen, professor of populations at the Rockefeller University in New York. That could cut the expected growth in the human population by as much as three billion by 2050. The present global population is 6.7 billion but would rise to as much as 11.9 billion by then if current trends continue. "Secondary education increases people's capacity and motivation to reduce their own fertility, improve the survival of their children and care for their own and the families' health," Professor Cohen said.

"Education promotes a shift from the quantity of children in favour of the quality of children. This transition reduces the future number of people using environmental resources and enhances the capacity of individuals and societies to cope with environmental change."

The growth in human population will exacerbate environmental degradation as more people compete – sometimes fiercely – for limited food, water and land. Attempts at limiting growth have concentrated on providing birth control to women, but secondary female education is seen as increasingly important.

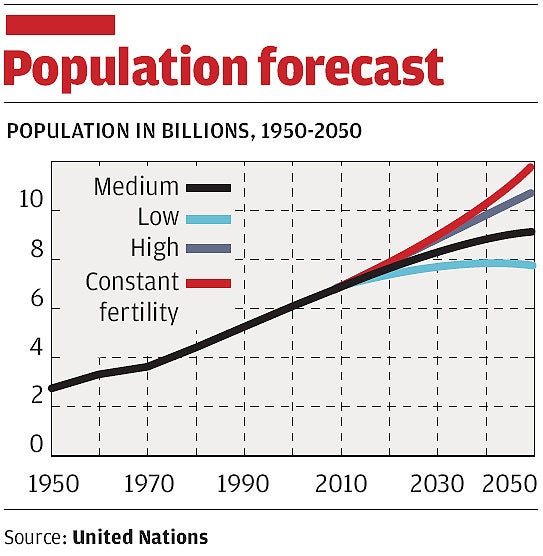

The United Nations estimates that the world population will hit 9.1 billion by 2050 and that most of this increase will be in developing countries in Africa and south-east Asia. But this "medium" estimate is based on fertility rates, that is the number of babies each woman has, declining from today's 2.55 children per woman to slightly over two children per woman by 2050.

If each woman has, on average, half a child more than the UN estimates, then by 2050 the world population could be as high as 10.8 billion. If each woman has half a child less, it could be as low as 7.8 billion, Professor Cohen said.

"Thus a difference in fertility of a single child per woman between now and 2050 alters the 2050 estimate by three billion, a difference equal to the entire world population in 1960," he added, writing in the journal Nature.

"Secondary education has the potential to influence that outcome dramatically. Although there are other factors at work, in many developing countries, women who complete secondary school average at least one child fewer per lifetime than women who complete primary school only."

In Niger, for example, women who completed secondary education had on average 4.6 children, a third less than women who completed primary education only.

The same is true of Yemen where women who completed primary education had 4.6 children on average, compared to the average of 3.1 children born to mothers who completed secondary school.

"One of the mechanisms by which education leads to lower fertility is likely to be reductions in child mortality. Parents who are more confident of the survival of their children have reduced incentives to have many children," Professor Cohen said. Unfortunately, in many developing countries, boys are significantly more likely than girls to go to secondary schools. In Benin, 38 per cent of boys go to secondary school compared to 17 per cent of girls, while in India, 58 per cent of boys are put through secondary education, and only 47 per cent of girls.

Professor Cohen said that it would pay for the international community to help to fund the education of girls in the developing world as a means of curbing global population. "For the next several decades, virtually all rises in numbers of people will occur in the cities of the less-developed regions. This vast shift presents an opportunity: it will be easier to reach the added children, and to attract and retain their teachers.

"Universal, high-quality primary and secondary education is achievable within 25 years. Educating all children well is a worthwhile, affordable and achievable strategy to develop people who can cope with problems foreseen and unforeseen."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks