‘Now they’re trying to get me’: The virus expert who caught coronavirus

Peter Piot is renowned for his research in the fight against Aids and Ebola, but when he fell ill with Covid-17 symptoms, he feared that doctor had become patient. He recounts what followed to Donald G McNeil Jr

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.“This is the revenge of the viruses,” says Dr Peter Piot, the director of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. “I’ve made their lives difficult. Now they’re trying to get me.”

Piot, 71, is a legend in the battles against Ebola and Aids. But Covid-19 almost killed him.

“A week ago, I couldn’t have done this interview,” he says, speaking recently by Skype from his London dining room, a painting of calla lilies behind him. “I was still short of breath after 10 minutes.”

Looking back, ruefully, on being brought down by a virus after a life as a virus hunter, Piot says he misjudged his prey and became the hunted.

“I underestimated this one – how fast it would spread,” he says. “My mistake was to think it was like Sars, which was pretty limited in scope. Or that it was like influenza. But it’s neither.”

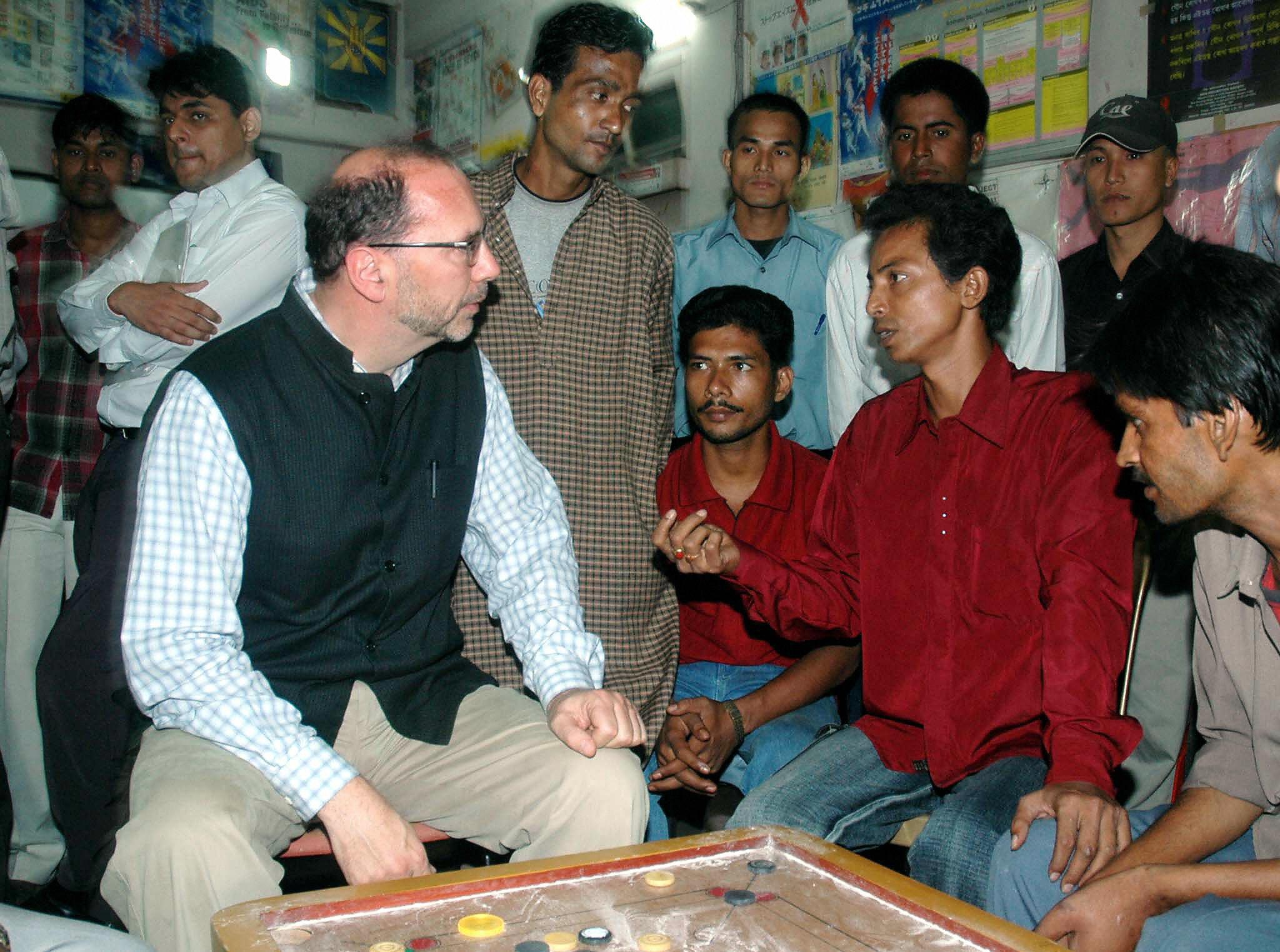

In 1976, as a graduate student in virology at the Institute of Tropical Medicine in Antwerp, Belgium, Piot was part of the international team that investigated a mysterious viral haemorrhagic fever in Yambuku, Zaire, now the Democratic Republic of Congo.

To avoid stigmatising the town, team members named the virus “Ebola” after a nearby river.

Later, in the 1980s, he was one of the scientists who proved that the wasting disease known as “slim” in Africa was caused by the same virus that was killing young gay men elsewhere.

From 1991 to 1994, he was president of the International Aids Society, and then the first director of UNAIDS, the United Nations’ anti-HIV program.

Extreme exhaustion, like every cell in your body is tired. And my scalp was very sensitive — it hurt if Heidi touched it. That’s a neurological symptom

That expertise made him keenly alert to the danger posed by the new coronavirus. In late January, he and his wife, Heidi Larson, an anthropologist, went to a medical conference in Singapore, which had had its first case a week earlier. While there, he gave an impromptu interview to local television on the day the World Health Organisation declared the emerging virus a public health emergency of international concern.

“We started banning handshaking from our behaviour,” he says. “We went out to eat because we like good food, but we started giving the ‘Ebola elbow’.”

In early March, he went to Boston with Larson, who heads the Vaccine Confidence Project at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. She gave a TedMed talk about rumours that damage vaccination campaigns, and he was asked 100 questions about the virus.

Number 79: “Should I be worried that I’m going to get Covid-19? How worried are you, Peter?”

He advised, “I would do everything I can to avoid becoming infected as you don’t know individual outcomes.”

He became a living illustration of that.

Although medical conferences in the Boston area that week were turning into super-spreader events, Piot almost undoubtedly did not get infected there.

Back home in London, he spoke to audiences of 30 to 250, attended a 50-person birthday party and had dinner or drinks in five restaurants in London or Cambridge.

“My usual modus operandi,” he says. Aside from avoiding handshakes, he took no particular precautions. “I really don’t know where I was infected.”

Although there were already many confirmed cases by that point, Britain did not officially go into lockdown until 23 March, when there were 335 confirmed deaths. Piot and his wife, by contrast, began working from home on 16 March.

On the evening of 19 March, he began feeling feverish and developed a headache.

“My immediate thought was, ‘Oh, I hope it’s not Covid.’”

Each day he felt more tired, his fever hovering around 100 degrees.

“It hit me like a bus,” he says. “Extreme exhaustion, like every cell in your body is tired. And my scalp was very sensitive – it hurt if Heidi touched it. That’s a neurological symptom.”

It was a new feeling. Despite all the time he has spent in mosquito-riddled climes, “I’d never been seriously ill in my life,” he says. A regular jogger and apparently healthy, he joked, “This is the first time in my adult life I didn’t drink wine for a month.”

Larson, on the other hand, has survived a fusillade of tropical diseases in her travels: cerebral malaria, hepatitis E, typhoid and dengue.

“I knew how a lot of the symptoms Peter had felt – how you hold your head when it hurts, how fatigued you get just moving across the room,” she says. “So if he asked for water, or anything, I dropped what I was doing and got it immediately. Time is a different experience when you’re not well – every minute matters.”

At the time, it was almost impossible to get tested; the few kits available were reserved for hospitals.

On 26 March, Piot finally found a kit through a private doctor. It was positive, and his fever kept rising.

On 31 March, it hit 104 degrees and he began feeling confused. He and his wife went to the emergency room of St Bartholomew’s Hospital. Although he did not feel short of breath, his oxygen saturation was only 84%, dangerously low. An X-ray showed fluid in both lungs in a pattern that suggested bacterial pneumonia.

His blood tests “were really bad”, he says. His levels of C-reactive protein, which indicates inflammation, and of D-Dimer, which indicates blood clots forming, were both very high.

“I instantly changed from doctor to patient,” he says. He was put on oxygen and sent upstairs on a gurney.

“That was when it hit me in the stomach,” Larson says. She was allowed to stay while he was assessed but could not venture upstairs.

Normally, NHS hospitals “are as crowded as Indian buses”, Larson says. “But they had a campaign saying, ‘Don’t come to the hospital unless you’re in the eleventh hour,’ so it was almost empty.”

She continues: “But when I saw Peter go through the double doors on that cart – I had the same feeling as the Ebola families we knew in Sierra Leone: they were hiding their relatives because they didn’t want to be separated from them emotionally, knowing they might never see them again.”

At first, Piot says, he was so exhausted he was apathetic. He asked for a single room but was told they were reserved for people who had not tested positive, for their protection. He was put in a 20-by-22-foot room, one bathroom, with three other men.

“They call the NHS ‘the great equaliser,’” he says. “The food was bangers and mash – awful.”

If this had happened before cellphones, can you imagine the loneliness? It’s like being in prison. Look, I know I’m privileged, and I know I’m not going to be stuck here for 27 years

Larson went home that night to hear on the news that Dr Gita Ramjee, a well-known South African Aids researcher, had just died of Covid-19. Ramjee was an honorary professor at Piot’s school and had led a symposium there before falling ill.

“She was my age, and I suddenly felt an acute sense of ‘it could happen to me,’” Larson says.

Piot was struggling with his own fears.

“All you can do is lie there thinking, ‘I hope it’s not going to get worse.’”

He got intravenous antibiotics and high-flow oxygen, and was roused every two hours for checks on his blood pressure and other vital signs.

“I was particularly anxious that I not be put on a ventilator,” he says. “Ventilators can save lives, but they can also do a lot of harm. Once you’re on one, your chances of surviving are the same as of surviving Ebola – about one-third.”

Every day, he talked to Larson or his grown children. He did get to watch episodes of a new series on the BBC of Inspector Montalbano, which his wife recommended.

“If this had happened before cellphones, can you imagine the loneliness?” he says. “It’s like being in prison. Look, I know I’m privileged, and I know I’m not going to be stuck here for 27 years like Nelson Mandela. But the world shrinks to the essentials. All you can think is, ‘How is my breathing going?’”

Finally, Piot says, his oxygen saturation came up to 92%. He was discharged on 8 April.

“They wanted to call me a taxi, but I said no; I wanted to breathe the now non-polluted air in London.”

He took a train home.

“It was a shock, like Stockholm syndrome,” he says of his survival. “When I got home, frankly, I started crying. It was so emotional.”

But his body wasn’t through with the disease.

Before the hospital released him, he had tested negative for the virus. But now something else was going on — a delayed immune reaction.

“Gradually, I became short of breath,” he says. “We live in an old Georgian house, with three floors, and I had a hard time getting upstairs.”

Larson bought a pulse oximeter, a fingertip monitor that measures blood oxygen levels.

She recently tested positive for antibodies to the virus herself, although her illness was so mild that she’s not sure when it peaked. She had two bouts of bad headaches, the first in late March and the second in mid-April. The second time, she also had itchy red eyes, which are a rare but recognised symptom and may indicate infection through the eyes.

On 15 April, Piot’s heart started to race to 165 beats a minute. The percentage of his blood oxygen dropped to the mid-80s again.

He and Larson went to University College Hospital, where he had a chest X-ray.

This time, instead of distinct bacterial masses on each side, “my lungs were full of infiltrates, and they were a real mess,” he says, adding, “It’s called ‘organising pneumonia’.”

The tiny sacs that grow like bunches of grapes throughout the lungs, he explains, were oozing signalling proteins – he was having a “cytokine storm”. Those drew voracious white blood cells into the spaces between the air sacs so they threatened to block the paths that oxygen normally takes to his red blood cells.

His doctors thought about rehospitalising him – an outcome he dreaded.

Instead, Dr Joanna Porter, who specialises in difficult pneumonias, put him on an intravenous steroid to reduce the inflammation, along with an anticoagulant to prevent blood clots from his atrial fibrillation.

NHS bureaucracy forbids her from discussing Piot’s treatment, although he gave his permission. He is still under her care.

In late May, a PET scan, CT scan and bronchoscopy subsequently showed that parts of his lungs had not completely cleared. “And,” he adds, ever the universal healthcare booster, “tell your American audience: all these expensive tests are free from the NHS.”

The steroids appear to be working, but taking them for too long can have side effects, including muscle wasting, weakening of bones and diabetes.

He may have to take anticoagulants for the rest of his life, he says, and parts of his lungs may permanently be scarred.

“But you can live with that,” he adds, shrugging.

“If you get this cytokine storm while you’re acutely ill, you’re finished,” he says. “But I had three stages – first fever, then needing oxygen, and now the storm.

“People think that with Covid-19, 1 per cent die and the rest just have flu. It’s not that simple – there’s this whole thing in the middle.”

© The New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments