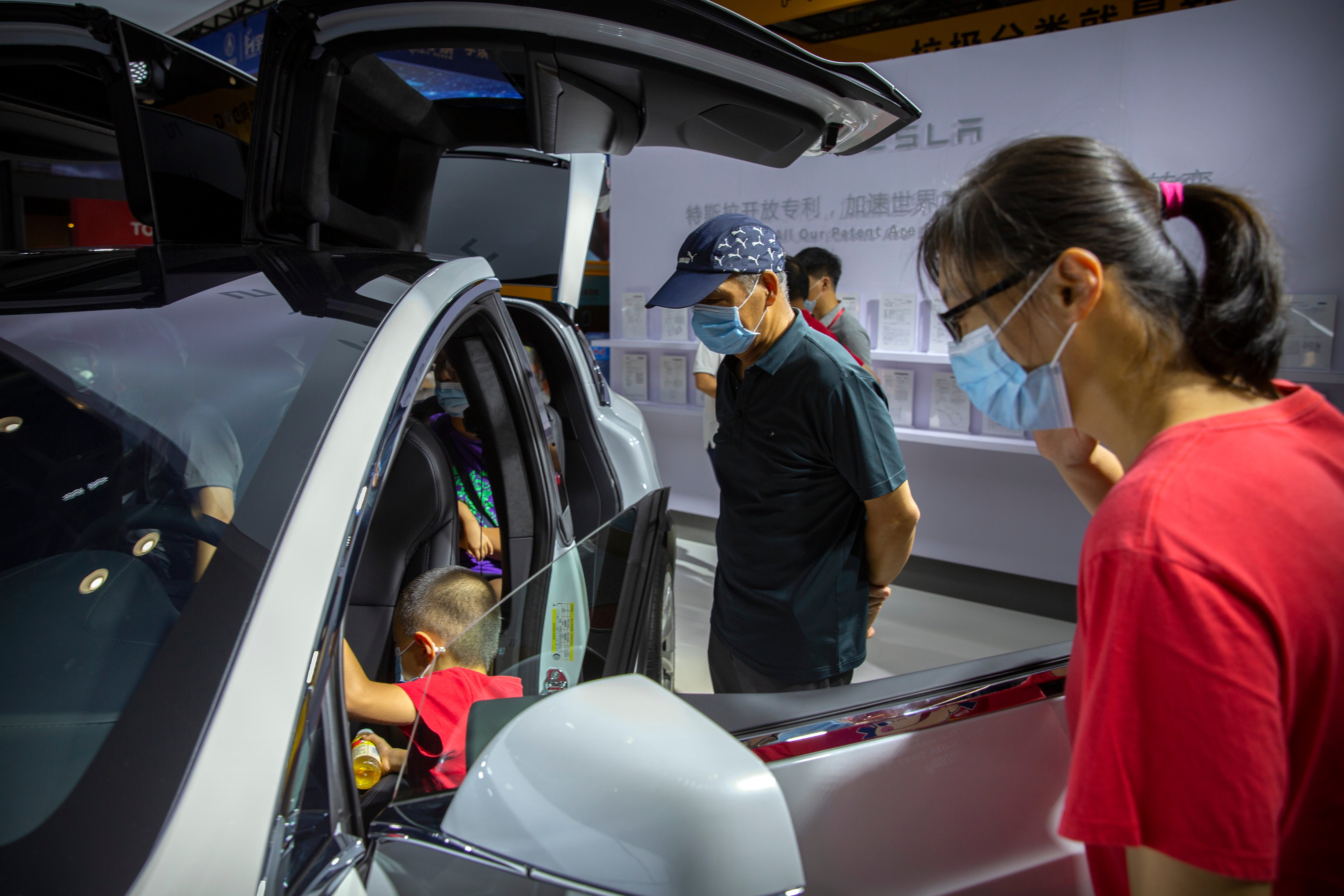

China auto show forging ahead under anti-virus controls

Auto executives have flown in early to wait out a coronavirus quarantine ahead of the Beijing auto show, the year’s biggest sales event for a global industry that is struggling with tumbling sales and layoffs

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The first event for the CEO of Swedish electric car brand Polestar at this month’s Beijing auto show: A two-week quarantine in a hotel.

The auto show, the first major in-person sales event for any industry since the coronavirus pandemic began, opens Saturday in a sign the ruling Communist Party is confident China has contained the disease. Still, automakers face intensive anti-virus controls including quarantines for visitors from abroad and curbs on crowd sizes at an event that usually is packed shoulder-to-shoulder with spectators.

“The car show will indeed be different from any other car show,” said Thomas Ingenlath of Polestar, owned by China’s Geely Holding, by phone from his hotel room in Tianjin, east of Beijing.

The automakers’ willingness to tackle the show’s logistical challenges highlights the importance of China, their biggest market. Chinese sales have rebounded to pre-pandemic levels while U.S. and European demand is weak and the industry struggles to reverse multibillion-dollar losses.

“China is the only hope for many global car makers,” said John Zeng of LMC Automotive Consulting. “They are really counting on China to help their bottom line.”

Ford Motor Co., General Motors Co., BMW AG and other brands are going ahead with global and China debuts of electric SUVs, luxury coupes and futuristic concept cars. Some are broadcasting events online to reach wider audiences.

CEO Makoto Uchida of Nissan Motor Co. and other executives plan to appear by video from their home countries. Most brands are relying on Chinese employees or foreign managers who work in the country full-time to operate their displays while keeping contact with spectators to a minimum.

China's auto industry has largely recovered since the ruling party declared victory over the disease in March and allowed factories and dealerships to reopen.

In August, sales rose 6% over a year earlier. Meanwhile, purchases in the United States were down 9.5% from pre-pandemic levels. Sales in Europe plunged 17.6%.

Automakers are responding by slashing workforces and shrinking operations.

Nissan is closing factories in Spain and Indonesia and cutting global production by 20% after reporting a $6.2 billion loss for the year ending in March. Groupe Renault SA is cutting 15,000 jobs worldwide and in April pulled out of its China joint venture with state-owned Dongfeng Motor Co.

To cut costs, Fiat Chrysler Automobiles NV and PSA Peugeot Citroen want to merge and create the world’s fourth-biggest automaker. But they face an investigation by European regulators into whether that will improperly reduce competition.

In China, the pandemic accelerated the consolidation of a fragmented industry with dozens of competitors by forcing a string of smaller local brands out of the market and bigger companies into alliances, said Zeng.

“That will change the industry landscape in the long run,” he said.

China’s major auto shows, held in Beijing and Shanghai in alternate years, are the industry’s biggest events, attracting every global automaker and dozens of new but ambitious Chinese brands.

The last Beijing auto show in 2018 had 1,200 exhibitors from 14 countries and 820,000 visitors, according to organizers.

This month's event, postponed from March, follows a smaller auto show in July in the western city of Chengdu with 120 exhibitors that was a trial run for anti-virus measures.

The Beijing city government has told automakers to limit the number of guests they invite but has yet to say how many people will be allowed into the 200,000-square-meter (2.2 million-square-foot) exhibition center. Rules issued by the city say everyone at the show should remain at least 1 meter (three feet) from each other.

Zeng, the industry analyst, said he was skipping the auto show because if leaves his home in Shanghai, his children would have to be quarantined after his return.

Polestar’s Ingenlath was tested for the coronavirus before being allowed to board a plane in Stockholm. He had a second test after landing Sept. 5 in Tianjin, one of several cities where visitors from abroad undergo quarantine before they are allowed to travel to Beijing, the Chinese capital.

“Really, to get emotion and the passion about the brand across, you can’t do that even with all the modern media we have,” Ingenlath said. “So I decided to go for a month.”

Polestar, spun off from Sweden's Volvo Cars in 2017 as a standalone brand, is one of dozens of producers that plan to display electric vehicles. They range from established global giants to independent Chinese competitors including BYD Auto Co. and NIO.

The Communist Party wants to make China a leader in the technology and has used subsidies and other support to transform it into the biggest EV market, accounting for about half of global sales. To spur competition, Beijing ended restrictions on foreign ownership of electric vehicle producers in 2018.

Ingenlath said he brought books but has had little time to read in between working online and dealing with coworkers by phone, email and online video.

“I have been going through pretty hard normal work routine,” he said.

Ingenlath’s 13-year-old daughter interviewed him for a classroom presentation about his quarantine. Barred from leaving his room, he set aside two hours a day to lift weights and do calisthenics “just to be able not to go crazy.”