Central banks' 'fifteen minutes of fame' is nearly over, says Mark Carney

The Bank of England Governor said it was ‘a much better balance’ for governments around the world to support growth through spending, rather than relying on monetary stimulus from central banks

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The Bank of England Governor, Mark Carney, has welcomed the prospect of central bankers moving out of the economic limelight as governments around the world spend more and rely less on monetary policy to deliver healthy growth.

“In many respects we’re coming to the last seconds of central bankers’ fifteen minutes of fame which is a good thing,” Mr Carney told the Bank of England Inflation Report press conference, referencing Andy Warhol’s line about everyone in the world being famous for fifteen minutes in their lives in the future.

The Bank has upgraded its 2017-19 growth forecast partly because of the boost to infrastructure investment in the November Autumn Statement by the Chancellor Philip Hammond.

Mr Hammond ditched the target of his predecessor, George Osborne, to achieve an absolute budget surplus by 2019-20, which many economists had argued was unnecessarily restrictive and harmful to growth.

Financial markets have also risen sharply since Donald Trump’s election last November in expectation that the new US President will deliver on his promises of major infrastructure spending and tax cuts.

The Bank of England – along with the International Monetary Fund and the OECD – have also upgraded their global growth forecasts on the back of this expectation of a material fiscal loosening from the US in 2017 and 2018.

“In general it’s a much better balance than the only game in town being central banks and monetary policy. This is positive,” said Mr Carney.

Asked about the recent comments by Peter Navarro, the head of President Trump’s new trade council, who this week accused Germany of using a “grossly undervalued” euro to undercut the US on trade, Mr Carney said: “I’m not going to quibble about specific comments in what is a generally positive direction of travel.

“Our job is to take other policies as given and that’s what we’ll do, whether that is UK policy or the policy of our major trading partners.”

After enacting fiscal stimulus in the global financial crisis of 2008 and 2009 in order to prevent the world falling into another Great Depression, Western governments embarked in a simultaneous fiscal consolidation in 2010 as ministers warned about rising national debt burdens.

But this turn to fiscal austerity is now widely seen as a mistake since it hammered growth and forced central banks into further monetary stimulus in order to support demand and prevent deflation taking hold.

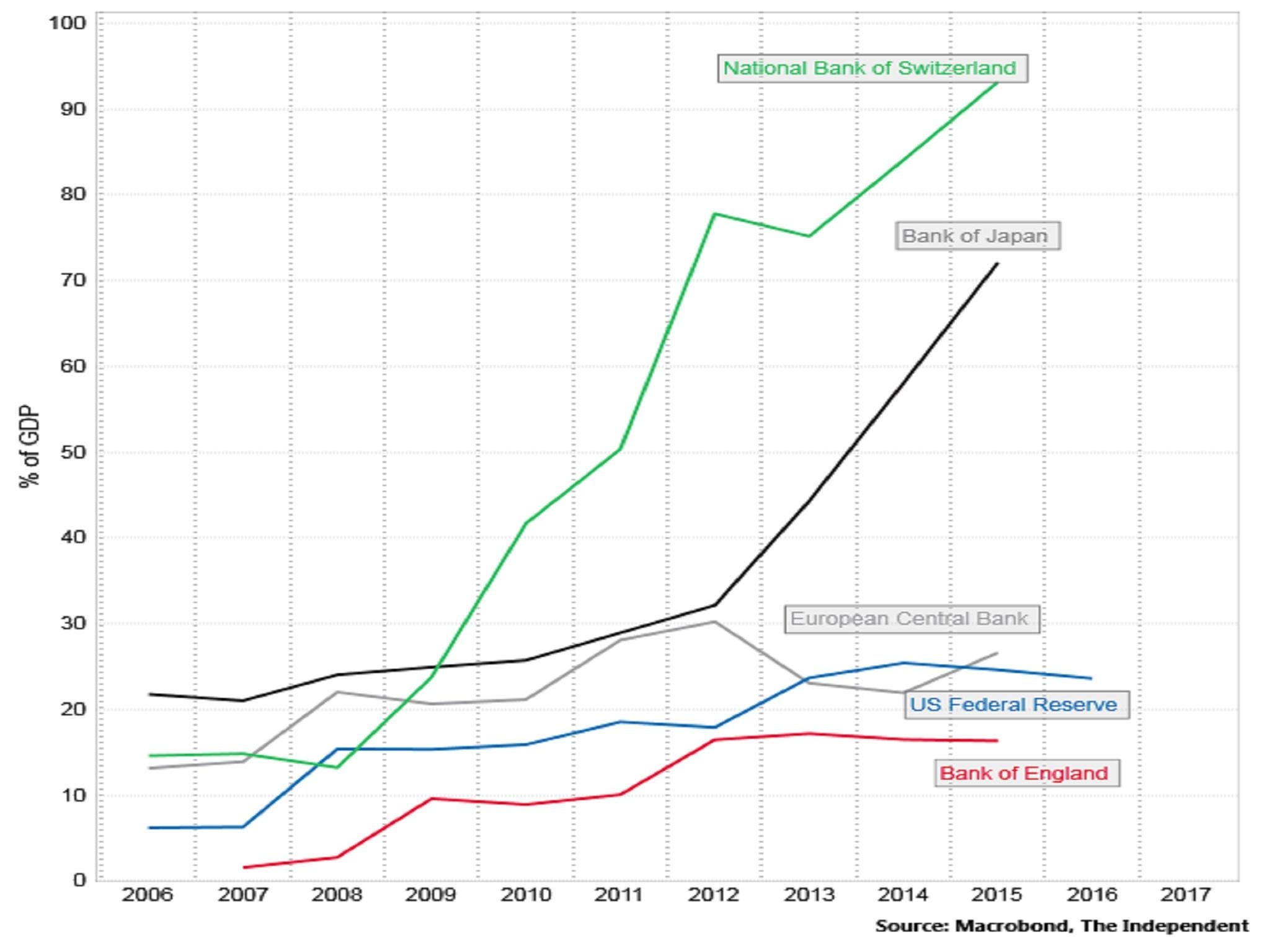

The balance sheets of the Bank of England, the US Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank have all ballooned to around 20 per cent of their respective GDPs as they have acquired government bonds and other financial assets in order to support demand since the financial crisis.

The Bank of Japan’s balance sheet is now worth more than 70 per cent of GDP and is projected to carry on growing as it seeks to restore inflation.

Central bank balance sheets have ballooned

The Swiss National Bank’s balance sheet is worth more than 90 per cent of GDP, as a by-product of its attempts to stop the damaging appreciation of the Swiss franc.

There have been widespread warnings about financial distortions arising from these central bank interventions, and they have come under attack from saving lobbies and politicians across the world for pushing down returns on savings.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments