Even if Britain beats OECD forecasts, it faces slow growth and high inflation

Britain suffers from a productivity problem driven by an investment problem, says James Moore

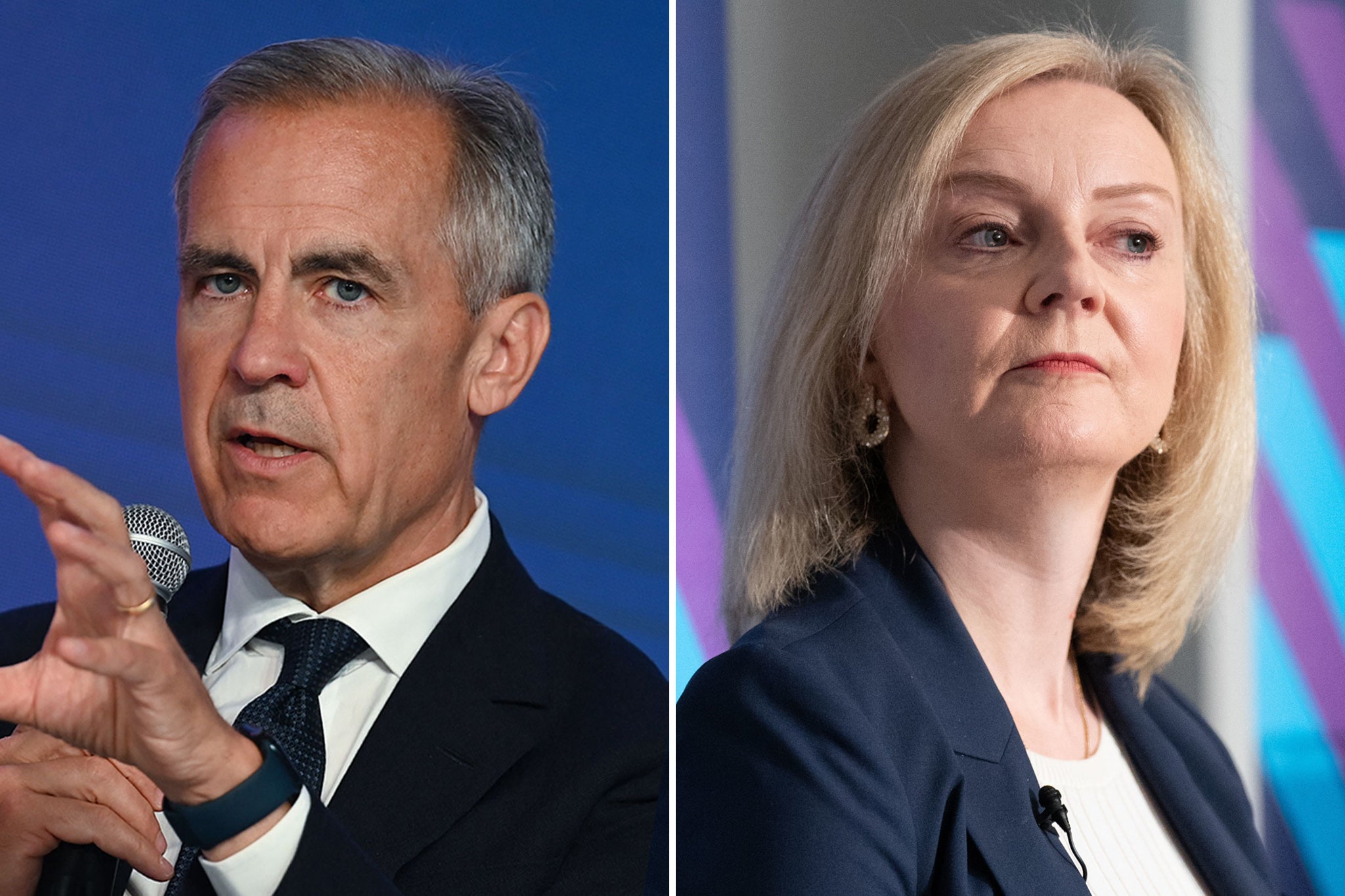

Barely a day after the Bank of England’s former governor, Mark Carney, accused Liz Truss of turning UK plc into a basket case – in stark contrast to her attempts to create a ‘Singapore-on-Thames’ – the OECD joined the fray.

In terms of economic growth, it said, Britain will this year beat Argentina and Germany.

But what about next year? OECD forecasters think Britain will still have its nose in front of Argentina... but not Germany. Nor any other advanced economy.

The UK is also expected to finish 2023 with the highest inflation of any G7 nation.

Truss attempted to fight back by railing against Carney and what she described as “the 25-year economic consensus that has led to low growth across the Western world” – ignoring the fact that she was outlasted by a lettuce.

But Carney had indulged in more than a little hyperbole in his jibe that “when Brexiteers tried to create Singapore on the Thames, the Truss government instead delivered Argentina on the Channel.” Yes, Britain has a problem with rising prices; but it pales in comparison to Argentina’s 124 per cent inflation rate, which has led to interest rates of up to 118 per cent.

There is no doubt that the UK has a growth problem; Truss got that right. The problem was created by her proposed solution – unfunded tax cuts for the rich – which sent mortgage rates spiralling and added an idiot premium to Britain’s debt costs.

Even if UK plc outperforms the OECD’s predictions, only a wild-eyed optimist thinks it will move out of the slow lane in terms of growth.

This will leave whoever occupies 11 Downing Street facing a long list of uncomfortable choices. Regardless of whether you favour tax cuts or extra funding for Britain’s creaking public services, you need growth to create the necessary fiscal headroom.

Politicians forget markets will ultimately do what they have always done: look at the numbers, and then act in their own best interests. There is no conspiracy do down Britain, to frustrate politicians or to deny the ‘will of the people’. If the numbers don’t add up, they will steer clear until they do.

Long term, Britain suffers a productivity problem driven by an investment problem. The latter is too low, a criticism that applies to both the public and the private sectors. Addressing it would be highly therapeutic. Rishi Sunak has tried offering tax breaks to stimulate business investment. Labour outlined some very ambitious plans before scaling them back somewhat. The electorate will soon have the chance to deliver a verdict.

In the shorter term, much depends on the Bank of England, led by Carney’s successor, Andrew Bailey.

There is a view that the Monetary Policy Committee ought to end its cycle of interest rate rises, to give its hard medicine time to work and to ease the pressure on an economy (struggling with rates of 5.25 per cent, for those looking to compare with Argentina).

Swati Dhingra, an external member of the committee, has long been making that case alongside her now departed colleague Silvana Tenreyro; there are a number of sensible types in the square mile and Canary Wharf who are coming around to the idea.

The most likely outcome still remains a quarter-point rise and thus more pressure on UK plc. Some small consolation: this might just be the last such rise.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks