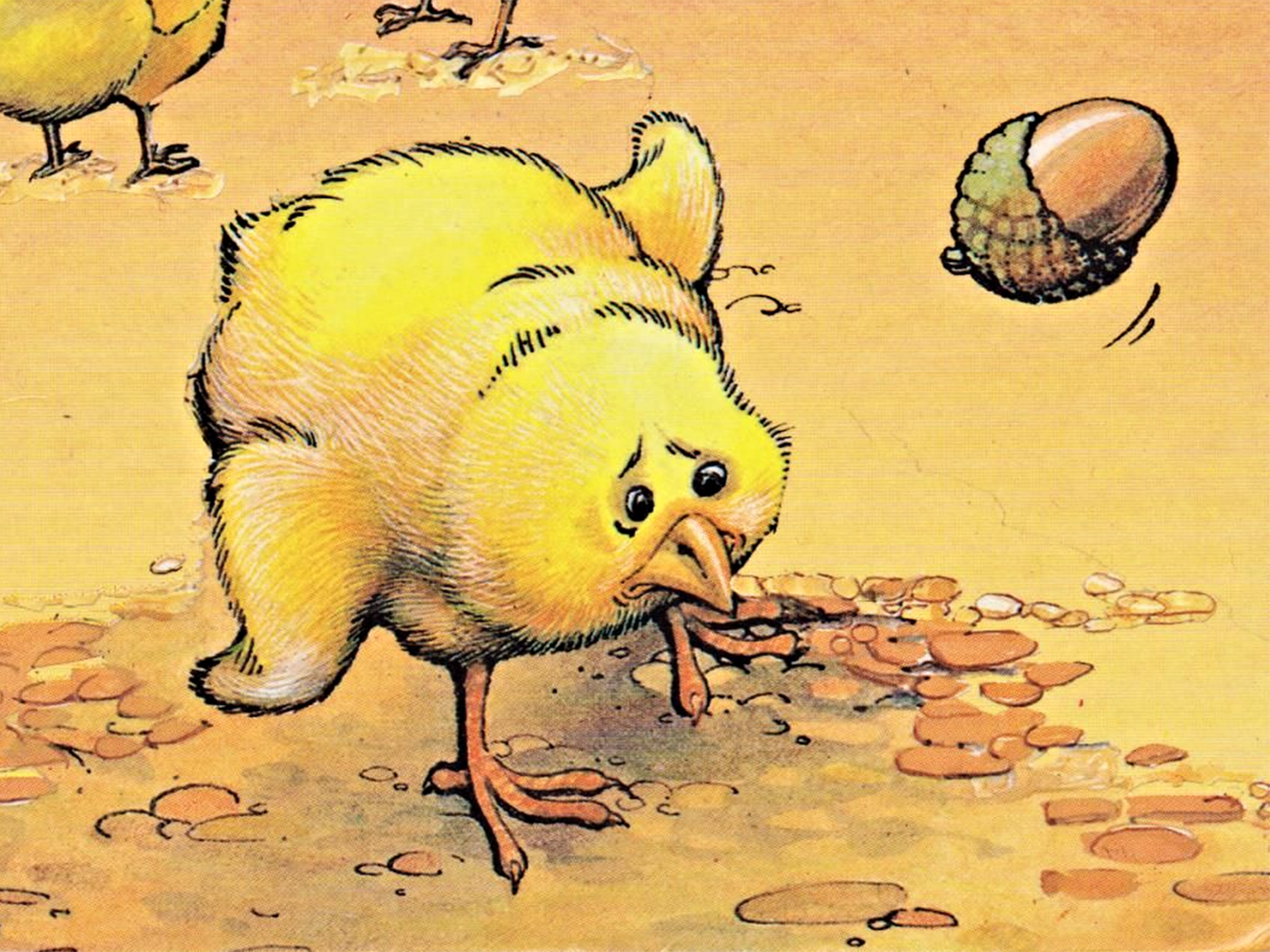

Are we being Chicken Lickens about the state of the UK economy?

The argument that unwarranted pessimism can be economically damaging is true, says Ben Chu. But we need to remember that is not a “normal” recession where one of the key goals of public policy is to boost public confidence

Chicken Licken felt an acorn fall on his head and thought it was the sky falling in. In the allegory, the foolish animal ran around, panicking other farmyard birds with his terrifying theory until, in the end, they all got eaten by a fox.

“Now is not the time for the economics of Chicken Licken,” argued the Bank of England’s chief economist, Andy Haldane, in a speech on Wednesday.

Which is true in the sense that it’s obviously irrational to panic about a non-existent threat. But Haldane was seeking to make a more profound point than that.

He points out that, despite the record-breaking slump in activity during the pandemic, the UK economy has actually performed better than expected earlier this year. Economic activity seems to have bounced back quicker than initially pencilled in by many economic forecasters, including the Office for Budget Responsibility and the Bank of England itself.

Yet Haldane feels that the media coverage – and especially the headlines – have been overly focused on the scale of the initial collapse in activity in April, rather than the more encouraging trend since then. He thinks this is not only giving audiences a distorted picture of what’s really going on now, but risks holding back the economy by depressing consumer confidence. The Chicken Licken-style hysteria of news organisations “fuels anxiety, heightens caution and risks becoming self-fulfilling”.

Haldane plea is for more balance – and not only from newspapers and broadcasters but also policymakers such as the bank itself.

“That means balance in how the economic outlook is described, acknowledging good news as well as bad, contemplating upside as well as downside scenarios, taking positive signals (as well as some comfort) from the resilience shown so far,” he says.

“This is not boosterism; it is balance, at a time when behavioural biases and pessimistic popular narratives offer an unbalanced lens on the economy.”

What to make of this? It’s certainly not silly to suggest that the way people feel about the state of the economy can affect the economy’s performance. If people believe other people are not spending for some reason they might well fear that their own employer is likely to suffer weak sales and perhaps make them redundant.

If people think they might lose their jobs they might cut their own spending in order to build up their savings in anticipation of an unwelcome shock to their personal finances. If enough people think and act in the same way that can bring on the very drop in spending that was feared.

Similarly, if businesses think the public are not spending, they might well put their investment plans on hold, which means less employment or orders for other firms, or maybe even make redundancies in anticipation of lower demand themselves. And around and around the broader economy the negative impact of the pessimistic belief flows.

Haldane says has a ‘Rooseveltian fear of fear itself’ referring to the great 1933 presidential inauguration speech by FDR. But in 2020 we do not only have fear to fear: we have a virus to be wary of

With household spending accounting for around two-thirds of all the spending that takes place in the economy consumer confidence really does matter. The kind of self-fulfilling cycle of pessimism that Haldane hints at describes important aspects of many modern recessions: people lose confidence for some reason, they stop spending, the economy stumbles and unemployment rises. The great insight of John Maynard Keynes was that economies can get trapped in these cycles of low confidence.

And as the Nobel economics laureate, Robert Shiller, has argued more recently, narratives are extremely important in affecting how people behave. If a popular narrative has taken hold that the economy is not recovering it’s not crazy to imagine that this can drive reality.

“Sometimes the dominant reason why a recession is severe is related to the prevalence and vividness of certain stories, not the purely economic feedback or multipliers that economists love to model,” says Shiller.

The questions is less whether this kind of phenomenon is possible, but whether it describes what’s happening in the UK economy today. Haldane notes that measures of consumer confidence have remained very depressed while measures of actual consumer spending have recovered in recent months.

It’s possible that this divergence is related to the doom-laden headlines about the state of the economy. But it’s also possible that it’s related to the fact that the chancellor has made it clear for months that the furlough scheme, which has kept millions of people in jobs since the lockdown, will end in November, threatening a cascade of job losses.

The new job support scheme – subsidising part-time work – offers nothing to those sectors with no work at all because of government health restrictions.

The furloughed nightclub manager, or the conference organiser, might not think the economic sky is falling on their heads now but many, not unreasonably, fear that happening in November.

It’s possible too that low consumer confidence is related to the fact that the virus has not disappeared but has been spreading in recent weeks, prompting the imposition of new restrictions which will damage many hospitality and retail businesses.

Haldane reasonably argues that the direct impact of those new restrictions on the overall economy need not be large. Yet what they underline is that this is not a “normal” recession, where one of the key goals of public policy is to boost public confidence.

Haldane says he has a “Rooseveltian fear of fear itself”, referring to the great 1933 presidential inauguration speech by FDR, during the Great Depression. But in 2020 we do not only have fear to fear: we have a virus to be wary of. And one of the means through which that virus spreads is – sadly – classic economic consumption activities such as shopping, celebrating and eating out in restaurants.

Haldane’s speech, in a sense, echoes the exhortation from the chancellor, Rishi Sunak, that the British people should learn to “live without fear” last week. But the route to achieving that is for us to – collectively – beat this virus, not to beat the media for being Chicken Lickens.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks