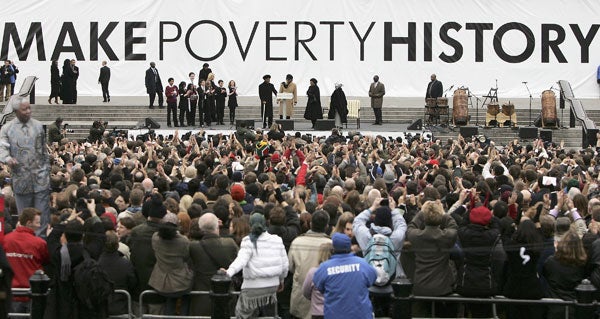

Business leaders say they must do more to make poverty history, but Oxfam says actions speak louder than words

More than 35 CEOs and other leaders have called for a more sustainable economic model, but talk is cheap and the Oxfam figure highlights the fact that inequality is growing and so is the instability that goes with it

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It’s Davos week, when the world’s wealthy gather in the Swiss resort for the World Economic Forum to do a bit of skiing, talk some shop, and generally congratulate each other on how well they’re doing.

In recent years they’ve also paid lip service to recognising the fact that billions of people aren’t doing so well as they are.

Partly that is because Oxfam, among others, does a good job of reminding them of that fact by regularly releasing reports showing the yawning and growing gulf between a few ultra wealthy individuals and the teaming masses of the world’s poor.

This year it highlighted the fact that just eight individuals collectively hold more wealth than half the world’s population.

Allies of those eight typically jump on Oxfam’s missives and say it’s focussing on the wrong thing. Better to concentrate on making the poor richer as opposed to thinking about ways to redistribute some of that vast wealth and thereby make the rich a bit less rich. The Thatcherite Institute of Economic Affairs predictably led that charge upon the release of Oxfam’s report.

But while making the poor better off is a good idea, and a noble goal to have, it doesn’t change the fact that such a yawning level of inequality is deeply problematic and relying on growth to pull people out of poverty isn't working as well as it might.

Oxfam, for example, points out that were growth evenly distributed in developing nations between 1990 and 2010, the number of people living in extreme poverty (defined as having to make do with less than $1.25 a day) would have been reduced by 200 million people.

The ultra wealthy grab an unequal share of global growth, slowing efforts to alleviate poverty.

There are people outside of Oxfam who recognise that there is a problem with an economic system that allows this to happen.

One of this year’s attempts to show that Davos cares came from one of them, the Business and Sustainable Development Commission, which was launched at the end of the last shindig to encourage businesses to take the lead in reducing poverty and encouraging sustainable development.

It includes some heavy hitters. Some 35 CEOs and civil society leaders, including the bosses of big firms such as fund manager Investec, Marmite maker Unilever, insurer Aviva, Alibaba, the Chinese e-commerce giant, Merck, the pharmaceutical group, publisher Pearson, and so on.

Its report is entitled Better Business, Better World and it is described as “a call to action to business leaders”. Were business to move to more sustainable models, focussing on the long term and playing a part in achieving the UN’s sustainable development goals, it says, businesses could unlock up to $12 trillion (£9.9 trillion) of economic opportunities and create 380 million jobs by 2030.

It also warns that a failure by businesses to pay more attention to the world in which they operate will result in malign consequences, fuelling environmental collapse, the continuing backlash against globalisation and some very bad politics (which we’ve already started to see).

Oxfam says that it is helpful that people like those on Commission, and some of those who have the top passes and invites to the best parties at Davos, are talking about things like this when they weren’t doing so a few years ago.

The trouble is pretty words and CEOs wearing tie dye shirts on dress down Fridays are all very well, but actions speak louder.

The CEOs of the firms mentioned continue to be awarded bigger and bigger pay packages despite little apparent link to economic performance. Aggressive tax planning is commonplace among multinationals, disadvantaging smaller firms and depriving governments of revenues. Small companies also suffer through bigger businesses' habit of dragging their feet over invoices. Long term thinking is the exception rather than the norm, with the focus overwhelming on quarterly or half yearly earnings. Fund managers rarely vote against bad boardroom behaviour. The destruction of the environment continues apace.

Governments, for their part, are reluctant to take hard decisions that might encourage better behaviour. When even relatively mild reforms are suggested, the business community’s lobbyists are quick to come forward with arguments against them. Witness Theresa May’s hasty backtracking on proposals to put workers on boards.

The Business and Sustainable Development Commission is right. There is a desperate need for a change in business thinking. You’d think that $12 trillion would tempt them. But there's little in the way of hard evidence to suggest a widespread recognition that the current model is failing.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments