The UK is definitely recovering but we simply don't know if it will last

Economic View: It is not only boring snoring to go around saying there is no recovery. It is plain wrong

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Two questions. Is the UK recovery real? And is it sustainable? It has become pretty clear that the answer to the first is yes, though you need to acknowledge the uneven nature of economic performance between the different regions. But the answer to the second is more nuanced. If you focus on the demand side, we have a recovery led by consumption. If you look at the supply side it is one led largely by services. Both are fuelled by very easy money and that at some stage will have to be reversed, but for the time being you have to be very pessimistic not to admit that there is quite a lot of growth around.

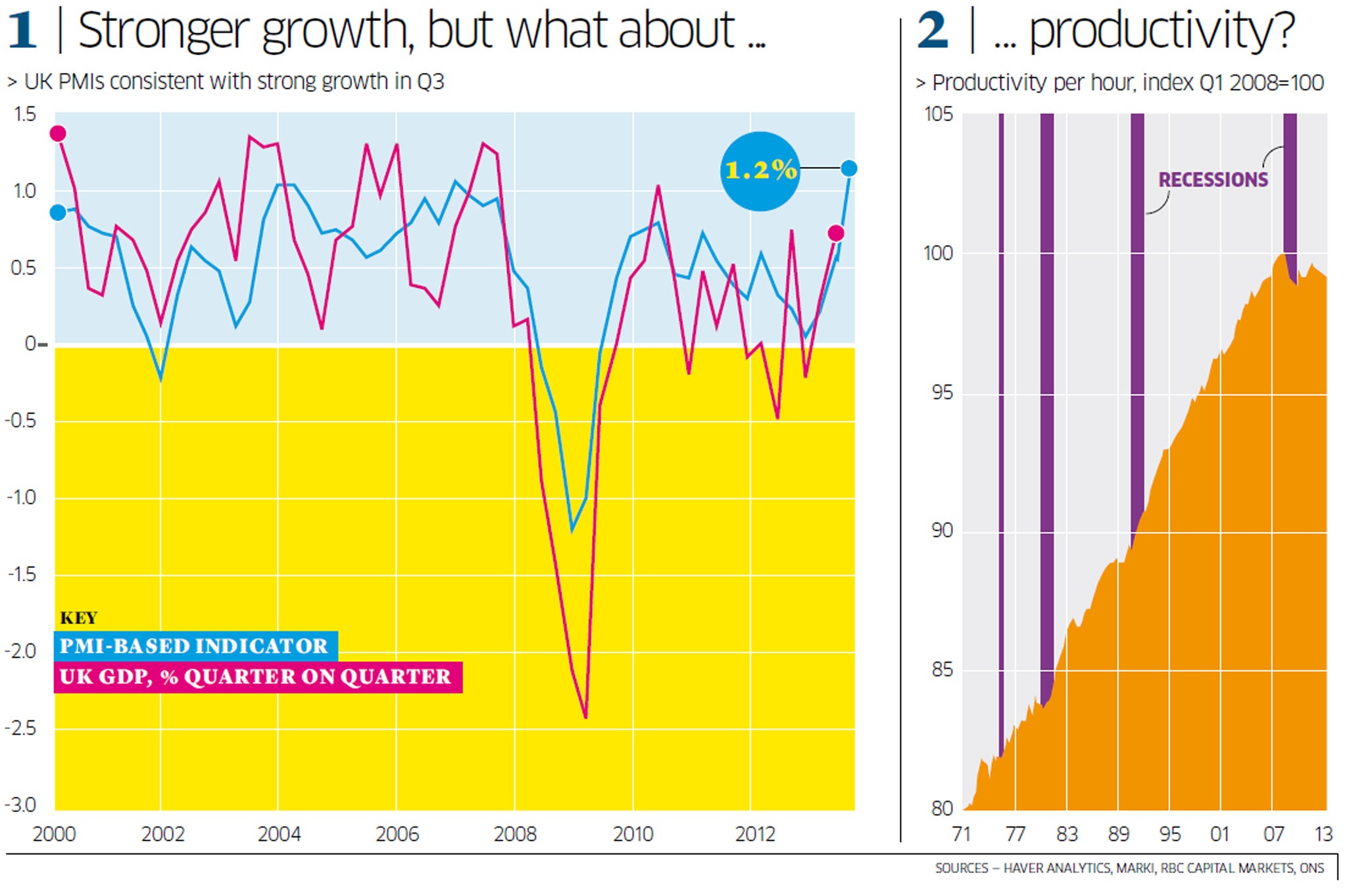

There are two sorts of economic data. There is the macro-economic stuff, which obviously includes GDP and employment, and also the purchasing managers' indices (PMIs), which give the best forward-looking indicator for what is likely to happen in the next few months. This is all strongly positive. You can see in the left-hard graph what has happened to GDP, together with a growth indicator developed by the capital-markets team of Royal Bank of Canada, looking at these PMIs. That suggests growth in the third quarter, the one that has just ended, of 1.2 per cent or nearly 5 per cent expressed at an annual rate.

The other sort is the hard data – hard numbers of what has actually happened, things such as car sales and so on. These are also positive. Indeed, September car sales at 403,136 units were the highest for over five years, up by more than 12 per cent on the previous year. Another bit of hard data that is worth looking at is tax revenue. There are some distortions but one encouraging number here is that in the first five months of this financial year total tax revenues were up 8.4 per cent on the previous year. In August VAT revenues were running 4.4 per cent up, which is good news because VAT covers something like 40 per cent of the economy. If that 40 per cent has been doing all right the chances are that the other 60 per cent will have been doing OK too.

I find this pretty conclusive. It is not only boring snoring to go around saying there is no recovery. It is plain wrong.

The more interesting issue is about sustainability. The argument runs something like this: it is of course better to have a recovery than not have one, but in an ideal world growth would be sustained by a mixture of exports and higher incomes at home. We don't really have that.

Part of the problem is weakness in our main markets. The balance of payments dipped further into the red earlier this year. Physical exports to the eurozone, which, unfortunately, is still our largest market, were poor, and while service exports remain strong they are not yet big enough to cover the gap. We don't have to run a current-account surplus, but we are attracting foreign investment from overseas. However, the deficit ought not to be more than, say, 2 per cent of GDP, and it pushed up to 4 per cent.

Barring some further disaster in the eurozone, prospects are slightly brighter. The latest export data is a little better. The eurozone taken as a whole seems to be nudging back to growth. And the artificial depression of the pound earlier this year, when it was talked down by the previous Governor of the Bank of England, has reversed itself. This is helpful because while you need a competitive exchange rate, an excessively depressed one pushes up your import costs and cuts export revenues – neither of which we need.

So, slightly better export prospects; what about domestic demand?

There are two big puzzles. The first is how people manage to increase consumption – buy more cars for example – when incomes remain depressed. The obvious explanation, that people are running down savings, does not really work because savings are not bad. The savings figures are difficult to interpret but it is clear people are still paying off mortgages faster than they need to, rather than borrowing more against the value of their homes.

The best explanation is to say there are several factors at work, of which the most important is rising employment. We as individuals are not seeing much of an increase in our income, maybe the reverse. But there are more of us in work and therefore the total pool of money available to buy stuff is rising. Add in slightly easier access to credit, money spent by foreigners here, spending funded by wealth rather than income, money from the payment protection insurance settlements by the banks, and increased consumption is not so surprising. Sustainable? Probably yes, but expect any build-up to be gradual.

The other puzzle is what on earth is happening to productivity. Have a look at the right-hand graph. For the past 40 years productivity has risen steadily in good times and bad. Then suddenly in 2008 it stopped rising and started to fall back. So a trend that seemed utterly solid has completely broken down. There are all sorts of possible explanations of which my favourite is that we are finding it almost impossible to measure output in the service industries, which is probably higher now than we think. But whatever the explanation, this is crucial for the durability of the expansion.

It is very simple. If we can expand output rapidly to meet demand then this growth phase will be much more durable than if we start running into bottlenecks in the next year or two. The answer to that is we simply don't know – and we need to be humble about the limits of our knowledge.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments