Rather than focus on jumpy markets, we need to take the long economic view

Economic View

Yes, but what about the real economy? When the markets have recovered their sense of proportion, and the captains and kings departed from Davos, what will matter to most of us will be whether the economic engine-room of the world is continuing to drive us forward.

However you see this latest hissy-fit of the markets – as an irrational response to cheap oil, or a warning of a financial crash in the emerging economies – the world economy will carry on growing. It may grow a bit slower and parts of it may have another recession, but the big picture remains one of progress. The natural state of the world economy is to grow, not just in absolute terms but in per capita terms too.

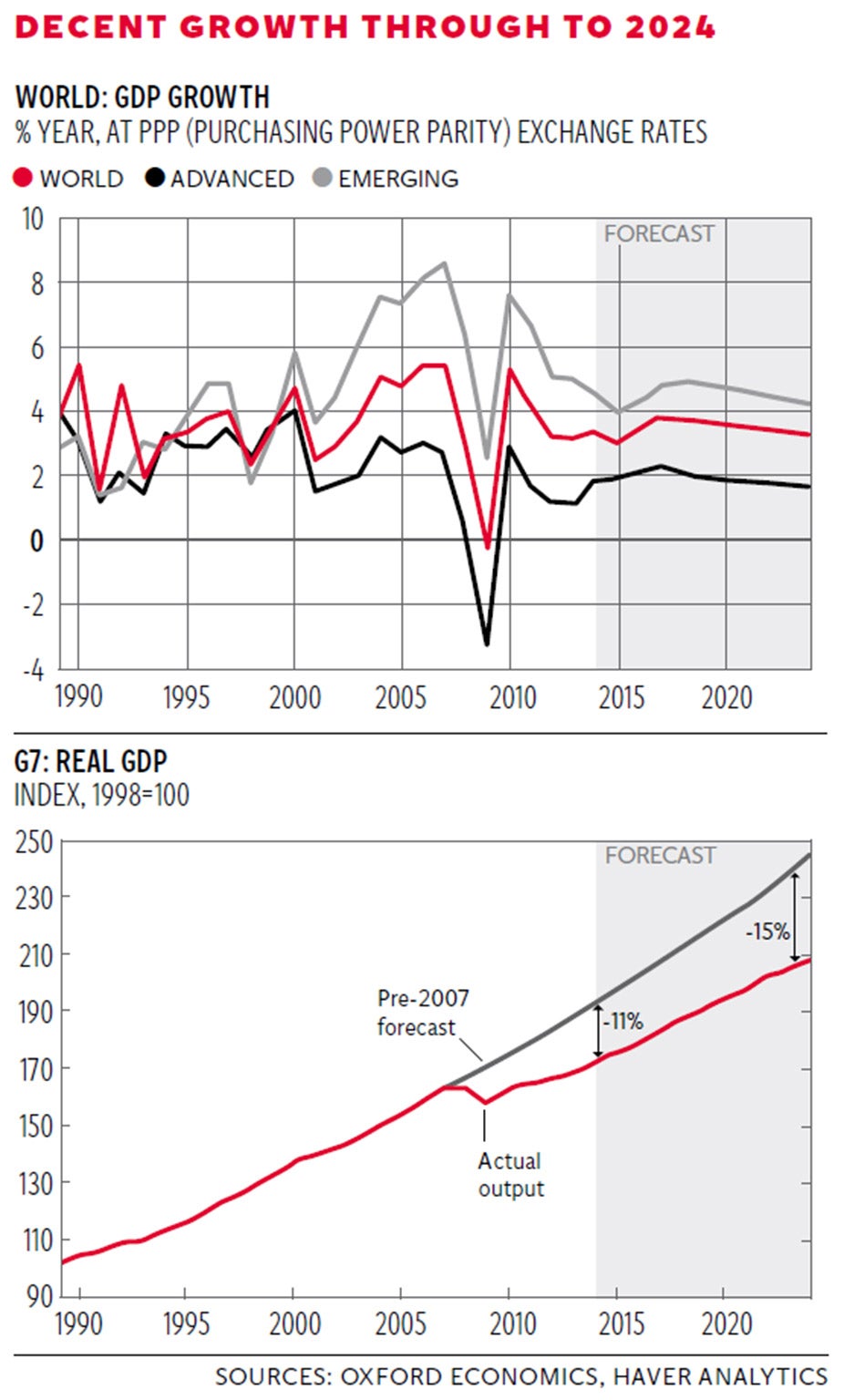

To put all this in a longer perspective, have a look at the graphs. At the top you can see global growth going back to 1989, plus some projections of what might happen running through to 2024. It comes from a briefing by Oxford Economics looking at growth prospects until then. There are a couple of obvious points here. One is that the emerging economies, taken as a whole, will continue to grow more swiftly than the developed ones, as they have since the late 1990s (note that they continued to grow right through the last financial crisis). The other is that overall trend growth for the world is forecast to remain positive at nearly the same rate, though maybe a little slower, as it was before 2007.

Actually the study suggests that growth will be 3.5 per cent between 2015 and 2024, which compares with 3.6 per cent from 1990 to 2014. Developed markets will manage 1.9 per cent, against 2.1 per cent in the earlier period. Emerging markets will achieve 4.5 per cent against 4.8 per cent. So yes, things will be a bit slower. But it seems to me that, given the huge uncertainties, there is not a lot of point in fretting about the odd tenth of a percentage point.

There is a further point to be made. That 3.5 per cent for the world compares with global growth of only 2 per cent a year between 1870 and 1950, when overall growth was held down by the poor performance of India and China. There are various explanations for that, but UK management of the Indian economy and the world’s interactions with China must bear some of the blame. Now that both of these giants are still growing swiftly, notwithstanding China’s recent slowdown, that 3.5 per cent figure appears achievable.

But this is a weak recovery for the developed world, with ground lost that will not be regained for a long time, maybe never. This less positive perspective is caught in the second graph, which shows the trend of GDP of the G7 countries up to the financial crisis, and what has happened afterwards. There is also a projection for what might have happened had there been no crisis, plus a projection of where GDP may go now. Oxford Economics calculates that by 2013 there was an 11 per cent loss from where output might have been, and that this will grow to a 15 per cent loss by 2024.

Put that way, the outlook appears a bit bleak. Add in the fact that the size of the workforce of the developed world has started to decline, and will continue to shrink though to the late 2030s, and you can paint a rather sombre picture. The world will be pulled along by India growing at about 6 per cent and China a little below that. But as China is so much bigger an economy than it was even a decade ago, its total contribution to global growth will be much the same. The paper makes the point that the chances of reverting to pre-1950 growth rates are remote. To dip back towards 2 per cent growth would require decades of lost growth in China and India and stagnation in the West.

I would make a further point. We may be under-measuring the output of developed economies now, just as we were over-measuring it in the run-up to 2007. We over-measured it then because consumption was artificially pumped up by excessive borrowing. Now much of the advances in our day-to-day living standards do not appear in GDP. For example, if we use the Google map on our phone to avoid a traffic jam, nothing appears in GDP. In fact, that may reduce GDP because we use less fuel. But our living standard is higher because we get there faster.

None of this is to dismiss the particular problems the world economy faces at the moment, of which the one that concerns me most is the burden of debt. I think all of us are aware that, were another recession akin to 2008-09 to loom, there is no ammunition in the locker to fire against it. But if policy is pretty powerless, it is worth remembering both that markets are self-correcting and that the world economy, left to itself, does grow. Maybe powerless policy is better than wrong-headed policy. I suspect that when the economic history books are written a generation or more hence, this era of ultra-easy money will be seen as more of the problem than the solution.

Meanwhile, we have to work with the world as it is, not as we would wish it to be. All long-term studies of equity markets observe that most of the return to investors comes in the form of dividends, particularly if re-invested, rather than pure capital gains. On a very long view, much the same applies to property and rent, even if the past 50 years seem to have proved an exception to this.

Equally, on a very long view, equities produce better returns than either bonds or cash, even if bonds have had a good few weeks. So I suggest the thing to cling on to, in these bumpy days, is that a world economy growing at 3.5 per cent a year for the next decade will, one way or another, produce higher living standards for most of us.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks