If EU can't restore prosperity to Europe, it's finished

The infuriating thing about Europe's current underperformance is that it ought to be doing so much better

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The noise drowns out the story. The din today included what seemed to be apparent about-turns by Wolfgang Schäuble, the German Finance Minister, and Jean-Claude Juncker, the European Commission president. Schäuble told the German parliament that Greece would remain in the euro for the time being, even if the Greek people rejected austerity, while Juncker told Alexis Tsipras, the Greek Prime Minister, that a bailout accord could still be reached. Tsipras’ new request for a two-year programme follows that.

All this rather supports the view of Tsipras that Europe would not kick them out of the eurozone because the costs would be too great. The less confrontational tone is surely welcome after the accusations which were hurled about over the weekend.

But paying too much attention to the latest statements by politicians is to ignore the central story. That comes in two parts. The first is what will happen to the eurozone; the second, and ultimately more important, is what will happen to the European economy.

We are learning more about both. The euro project first: rationally the actions of a country like Greece, which accounts for less than 2 per cent of the eurozone economy, should not have that big an impact on the financial markets. Yet it is not only the euro that has fallen. European shares have plunged. This morning the German DAX index was more than 5 per cent down on the level of a week ago – though it perked up on the Schäuble comments.

Even our own share markets are down, though Greece is a tiny market for our exports. On the other hand, the flight to quality has pushed up the prices of German bunds and UK gilts, as well as enabling the pound to climb to its highest level against the euro since 2007. So what have we learned? Well, there is certainly huge political will to try to hold the eurozone together, but we knew that already. The surprise, I suggest, is that the prospect of such a small defection should have such a negative impact on markets. It is widely accepted in Greece and outside that it was a mistake for Greece to join. A general rule in finance, and indeed in life, is that if you make a mistake, it is best to reverse it as soon as practicable. Yet the markets have reacted very negatively to that possibility; in that sense Tsipras must be right.

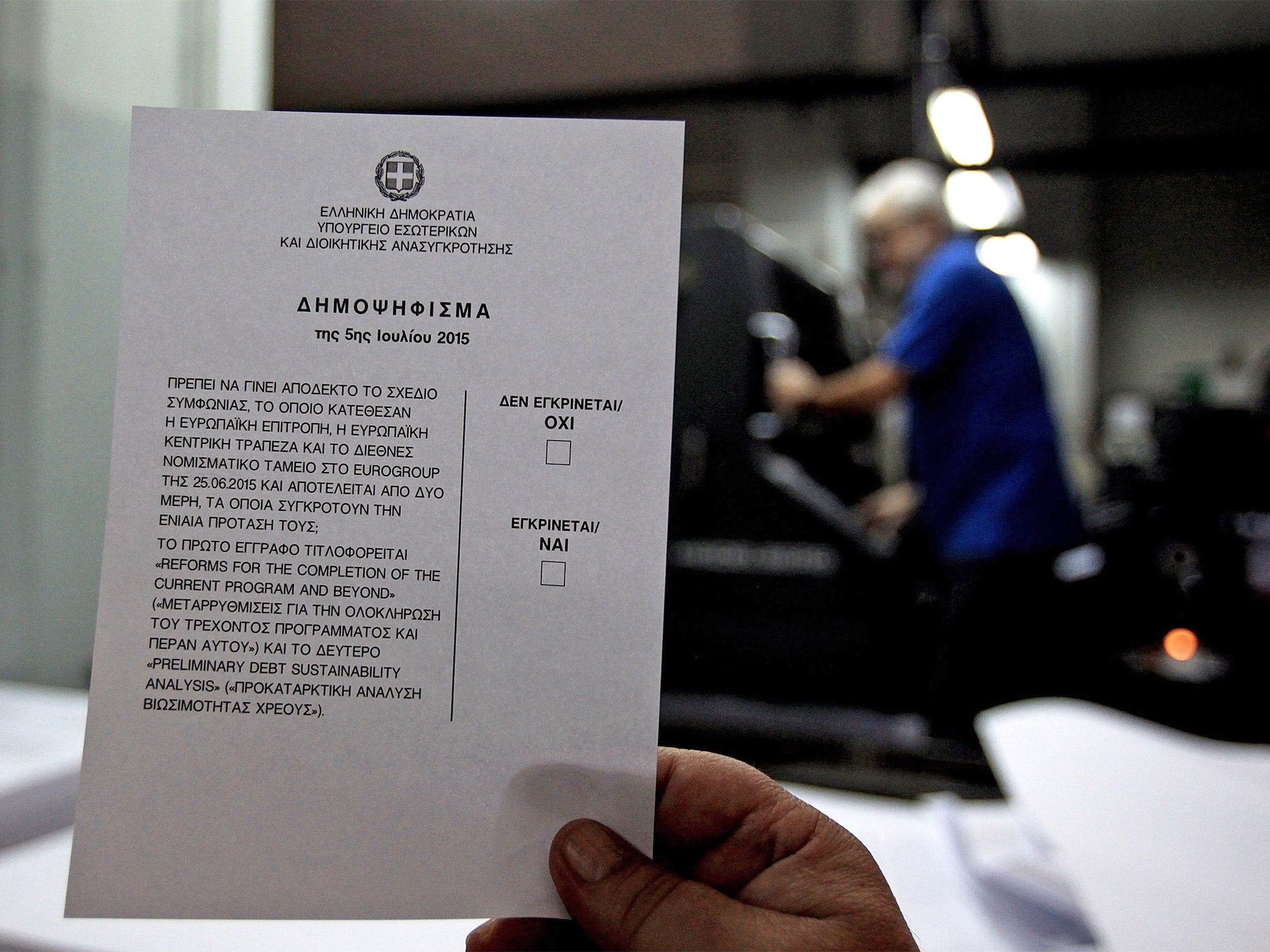

That indicated something very worrying about the inherent stability of the eurozone. Those troubles will not go away, whatever the Greek people decide in the referendum on Sunday. So Europe, and indeed the world, will have to live with concerns about the future of the euro for some time. I personally expect the eurozone to split into two, a hard euro and a soft euro with capital controls in between, but whether that is right or wrong, or even a sustainable option, is irrelevant.

We do know that doubts about the eurozone will persist, just as we know with near total certainty that Britain will never join it.

That leads to what seems to me the even bigger issue: the European economy. Angela Merkel famously said “if the euro fails, Europe fails”, but that is open to challenge. It is easy to envisage a European Union with national currencies – we had one until 15 years ago. But if her comment was reformulated as “if the European economy fails, the EU fails”, it would be hard to counter.

There is a creeping fear, supported by the events of the past few days, that the EU is not succeeding in making Europe richer. If the EU is starting to subtract from European wealth, rather than add to it, then the concept is done for.

Evidence of European underperformance is mounting. Greece is the extreme example, with its unemployment at over 25 per cent, but Italy, Portugal and Spain have unemployment rates of 12 per cent, 13 per cent, and 22 per cent, among the highest in the developed world.

Some EU economies are good at creating jobs, including Germany and ourselves, but as a region we are poor performers. Overall growth rates have been similarly poor, with the eurozone in particular growing at a slower rate than non-euro countries, and the rest of the G7, since 2000.

The management consultancy McKinsey published a report earlier this month which suggested that the underlying long-term growth rate of the EU was, at most, about 1 per cent. If that is right, then Europe has a huge problem – and a problem that goes beyond the obvious rigidities imposed by the single currency.

McKinsey suggested some ways in which Europe might lift its game, enabling 2-3 per cent annual growth. These included boosting the proportion of the population in the workforce (something we have done in the UK), better education and training (something we are less good at), encouraging innovation and so on.

It estimated that three-quarters of all these drivers for growth could be implemented by national governments. In other words, we only need the EU bureaucracy for a quarter of the things that might improve performance. Anecdotally, many British businesses feel the EU at present subtracts from performance by imposing unnecessary costs, though that charge is hard to assess.

The tantalising, infuriating thing about Europe’s underperformance is that it ought to be doing so much better. Individually the different European countries have huge reservoirs of skills, highly successful companies, great educational establishments and so on. But if it is world class at many technologies, it is also a global brand leader at creating unemployment. What has happened to Greece has highlighted a wider economic malaise. And that surely is the bigger story.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments