Hamish McRae: Why selling our treasured assets to foreigners can make a lot of sense

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Would it matter if Cadbury were to fall into US ownership? Should we care that Opel and Vauxhall are being bought by a Canadian-led consortium? Or that Volvo may be taken over by the Chinese?

We have been pretty relaxed in the UK about foreign companies owning our ones, more relaxed than just about any other large developed nation. In the case of the motor industry we made that decision a long time ago. Vauxhall was a British manufacturer of high-performance cars that was bought by General Motors as far back as 1925. (By the way, "real" Vauxhalls – those built before 1926 – are much prized today.) The result is that there is now no significant British-owned manufacturer. That might seem a bit sad given the number of iconic global motor brands the UK has created over the years but there is a positive case for foreign ownership in that the risks are widely spread. More manufacturers from more countries have plants and design teams in the UK than in any other part of Europe. And, although it is a niche business, we are also the main centre for building and designing racing cars.

So is the idea of Magna owning Vauxhall, and of course the much larger Opel, a good one? All our experience of foreign ownership would suggest that you simply cannot say. One of the greatest puzzles of corporate life is what makes some takeovers succeed and others fail. One would have imagined that Ford, with all its resources, would have been able to make a go of Land Rover and Jaguar, or indeed of Volvo. Why did BMW succeed with the new Mini but not with Rover? Why does India's Tata have a fighting chance of making Land Rover and Jaguar work? My instinct is that the Magna deal will not be a great success. If the success or otherwise of domestic mergers is hard to predict, adding an international dimension makes it doubly hard.

Take Cadbury itself. Until last year it was called Cadbury Schweppes, for way back in 1969 it had merged with the soft drinks company. It seems, however, that there is no great synergy between chocolate and soft drinks apart from neither being exactly health foods, and a year ago the US drinks bit was spun off. It is now called the Dr Pepper Snapple Group Inc, a name that must sound better in American than it does in English.

There are, however, a number of rational reasons why mergers ought to work, even if often they don't. One is that countries with a large domestic market can use that as a springboard to create world-beating companies. That is what the US did between the wars, when it built up European production of Fords and GM bought Opel and Vauxhall. Japan did much the same from the 1970s onwards, while China and India seem to be doing it now. But there is a twist here. You don't just need a lot of consumers – you also need them, ideally, to be sophisticated ones.

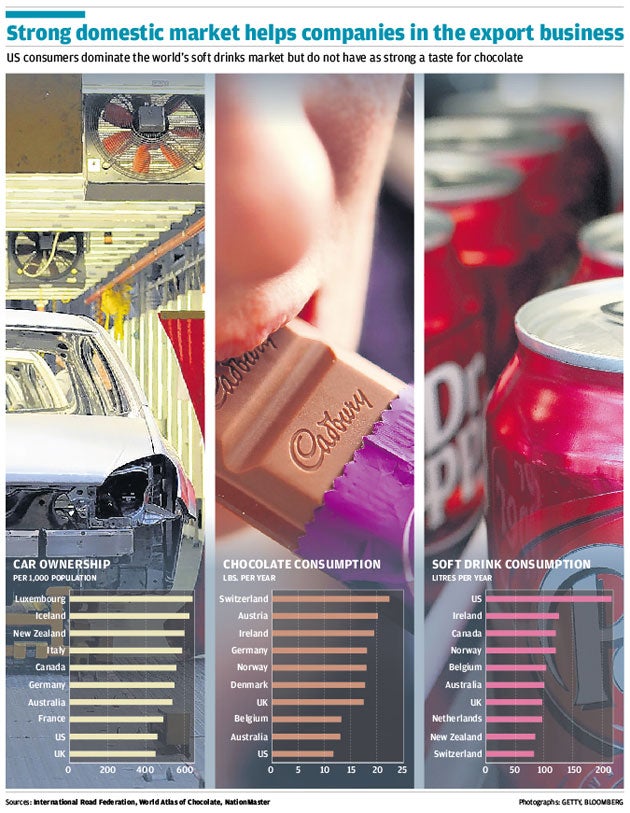

In the case of cars, the highest penetration of ownership may be in tiny Luxembourg (see table) but Germany, France and the US all have a clear car culture. The trouble US companies have run into is that their customers have less sophisticated tastes than car-buyers in the rest of the world: they want trucks and SUVs. The result is that most US-made cars are virtually unexportable and Ford of Europe and Opel/Vauxhall have had to be run as quite separate entities. In the case of Italy, the problem is the reverse. Italians arguably are too fond of cars, wanting style rather than durability. At any rate Italy has found it hard to sustain an export business. Of course the parallel does not always work. Japan has relatively low car penetration and many of the vehicles sold are tiny mini-cars. However, the genius of Japanese manufacturers has been that they have managed to cope with different tastes around the world.

In the case of chocolate, the country with the highest consumption is Switzerland, home of Nestlé. We are towards the top of the pack, above Belgium, that other great chocolate-producing nation. But our own taste is somewhat different from that of most Europeans and Cadbury has been clever to cope with that. Americans, as you can see, are not really into chocolate, though they are stunningly into soft drinks. Possible moral: Cadbury was right to spin off the business because we don't have any competitive advantage in this field.

But none of this is mechanistic. Just as you get companies that break all the management rules and are tremendously successful, so you also get countries which you might imagine have no competitive advantage at some particular activity and which do it wonderfully well. Think Finland and mobile phones.

But when you look at national strategy – do you run an open house for foreign investment? – I think you can make a good argument that the UK has made the right choice. The reason is not so much that most foreign investors have managed our firms better than we could, though on balance that may be the case. Nor is it that, by and large, non-national companies seem to treat their workforces better than domestic companies do, though again there is some evidence that they do. No, the argument is simply a financial one. It is that we make more foreign earnings on our investments abroad than we pay out on foreign investments in the UK.

We had a total investment income from abroad last year of £262.2bn, and we paid out £235.0bn. If you take direct investment, that is income from British plants abroad, we had credits of £69.2bn and debits of only £10.6bn. In short, we may have sold many of our companies to foreigners, but we own a lot overseas ourselves and we make a huge profit on the deal. These investment income figures, I should add, are separate from the earnings from financial services, which also ran at record levels last year.

This is not to deny that there are disadvantages of having UK assets owned abroad and there have been some missteps. Most of us would rate the sale of BAA to a Spanish construction company with very little experience of running an airport as one of those. But the overall performance is undeniable.

If Cadbury does pass into foreign ownership that might seem a bit sad, given the firm's Quaker roots and its record as an enlightened employer. But it would be hard to argue that chocolate, or the company's other products, have national strategic significance. Meanwhile, let's hope my instinct over the future of Vauxhall is wrong and that Magna will be a better steward of the company than General Motors has been over the past 84 years.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments