Hamish McRae: What's happening across Europe is good for tourists but bad for pensioners

Economic View: The fact that the pound now buys 20 per cent more euros that it did a year ago will for many of us be a welcome bonus

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

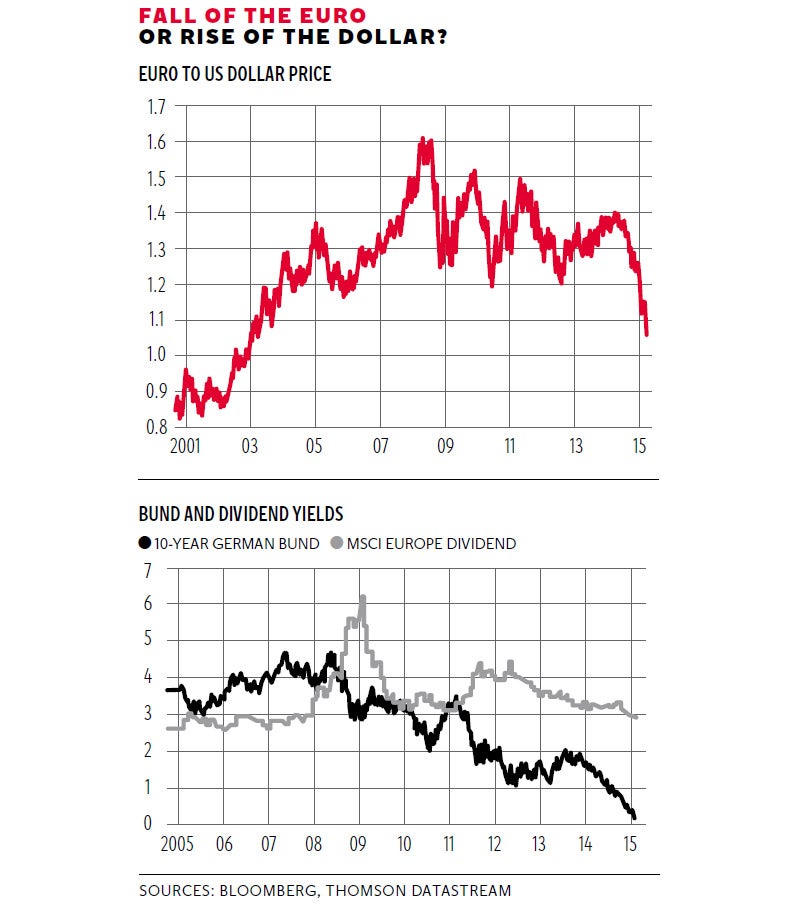

Your support makes all the difference.It does indeed look very much as though the euro will drop to parity with the dollar. The past few days have seen a plunge down to €1.06 and most currency commentators seem to think that this is just a matter of time. But the fall raises a string of questions: Does it matter? What are the longer-term consequences? Is this more about dollar strength than euro weakness? And is the European Central Bank’s quantitative easing programme being successful even before it starts?

From our own narrow perspective as individuals, this is thoroughly good news. We like a strong pound. The rump end of the skiing season is still ahead and the summer hols are not that far off. So the fact that the pound now buys 20 per cent more euros that it did a year ago will for many of us be a welcome bonus. The pound was pretty close to parity with the euro at the end of 2008 and is now €1.40. Suddenly, Europe has become cheap.

But this is not really a sterling thing. It is a euro and dollar thing, because the relative attractions of the two currencies have shifted radically. We have ridden up a bit on the coat-tails of the dollar, for if the US Federal Reserve increases dollar interest rates in June, we will presumably be not far behind. As far as the euro is concerned, with Europe offering negative returns on shorter-dated sovereign debt, it is a bit of a no-brainer either to get out of the currency, or at least switch to European equities. Indeed, one of the reasons for the quite sudden plunge in European sovereign yields seems to have been foreign holders baling out in advance of the ECB bond-buying programme.

In other words, the weakness of the euro is not driven by all the shenanigans over Greece. It is about interest rate differentials.

So the headlines are that the euro is at its lowest against the dollar for 12 years, which is quite correct. If, however, you take a rather longer view, maybe the movement is not so remarkable after all. The top graph shows what has happened to the euro and the dollar since 2000. As you can see the present plunge is certainly pretty precipitous, but on a 15-year view maybe the odd period was the overly strong euro between 2004 and the middle of last year that was the oddity. The euro was a lot weaker in its early years than it is now. Maybe parity is the right level, at least while the European economy struggles back to reasonable growth.

The problem of course is that parts of Europe do need a weaker currency but other parts do not. Germany, already super-competitive, will become yet more so. Italy may not be fully competitive even at parity with the dollar. Greece ditto. Nevertheless a weaker euro will be one element of the eurozone recovery, and may turn out to be the main way in which QE in Europe will add to growth. Cheaper money cannot really boost investment or consumption, because money is already very cheap. It may even have a perverse effect in that by cutting the return on savings, it may end up cutting demand in the more thrifty European countries. But devaluations ought to boost external demand; looking at the eurozone overall, that does seem to be happening. Star performers, notably Ireland, are coming up very fast. You can understand why Mario Draghi, president of the ECB, has been purring about the success of his actions.

What about the downside? I can’t see this damaging the United States much. The dollar is stronger than it was, but it is not over-strong by past standards. The US does not export that much to the eurozone, anyway. There are individual industries and companies that are affected: this is bad news for Boeing vis-à-vis Airbus. But the business world has learnt to live with currency swings and companies seek to balance revenues against costs, and by past standards what we are seeing, while sharp, is not yet extreme.

From our own point of view the position is somewhat different. Europe is a big market; one of our structural problems is being too reliant on it, for it is likely to be slow-growing over the next couple of decades. In the short-term we become a yet more attractive market for European exporters, while exports become tougher, and the question is whether higher demand from Europe will offset the price disadvantage we face. I suppose the best hope is that as the fall in sterling five years ago did not do much to boost demand, the present rise will not do much to damage it. We will see. Meanwhile remember that the largest single country to which we send exports is the US and sterling is still competitive against the dollar.

What should worry us more is the law of unintended consequences. A negative yield on shorter-dated eurozone debt leads to longer-term distortions. Foreign investors can vote with their feet. As you can see from the bottom graph, one obvious shift is from German Bunds to German equities, for the latter still give a solid yield. But within Europe many institutions are locked in to sovereign debt. Many pension funds rely on interest on bonds to pay pensions. How do you fund the monthly payments you have to make if your bond portfolio, when redeemed, is replaced with stock paying a zero or near-zero interest rate? As you can see from that graph, 10-year German Bunds bought between 2007 and 2009 will still be yielding 4 per cent. The bonds that were issued in 2005 and are now being redeemed have been giving you more than 3 per cent. But the bonds being issued now offer just 0.2 per cent. How on earth do you pay a pension on that? The longer these rates persist the worse the situation becomes.

The central point here is that extreme policies have extreme consequences. The world can cope with currency swings because it has experience of that in the past. But it does not have experience of zero or negative bond yields, and that’s very worrying indeed.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments