Hamish McRae: Wanted - Confidence booster from ECB

Economic View

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The focus shifts back to Europe. This week, it will be the turn of the European Central Bank to take over the baton of monetary easing, with a cut in interest rates widely expected after its governing council meeting on Thursday in Bratislava – one of the two monthly meetings it holds each year away from its headquarters in Frankfurt.

Nothing is certain but, given the hints and leaks, it would be a pretty big shock were the ECB not to do anything. So a cut of its main policy rate from 0.75 per cent to 0.5 per cent is overwhelmingly likely and the interesting issue will be what else it does to boost lending in Europe, particularly fringe Europe.

Something has to be done. Demand across a vast swathe of southern Europe has collapsed, as has been widely reported. But it has also weakened in the hitherto stronger parts of the eurozone, including even Germany. The German purchasing managers' index for April fell below 50, suggesting that the economy would contract in the second quarter of this year. The fact that inflation in the eurozone is now 1.7 per cent, comfortably below the 2 per cent ceiling, gives the ECB some leeway to act.

This leads to a narrow question and a wider one. The narrow is whether a cut in interest rates is going to boost lending in Europe; the wider is whether we are seeing the limits to monetary policy, or you might say, central bank power.

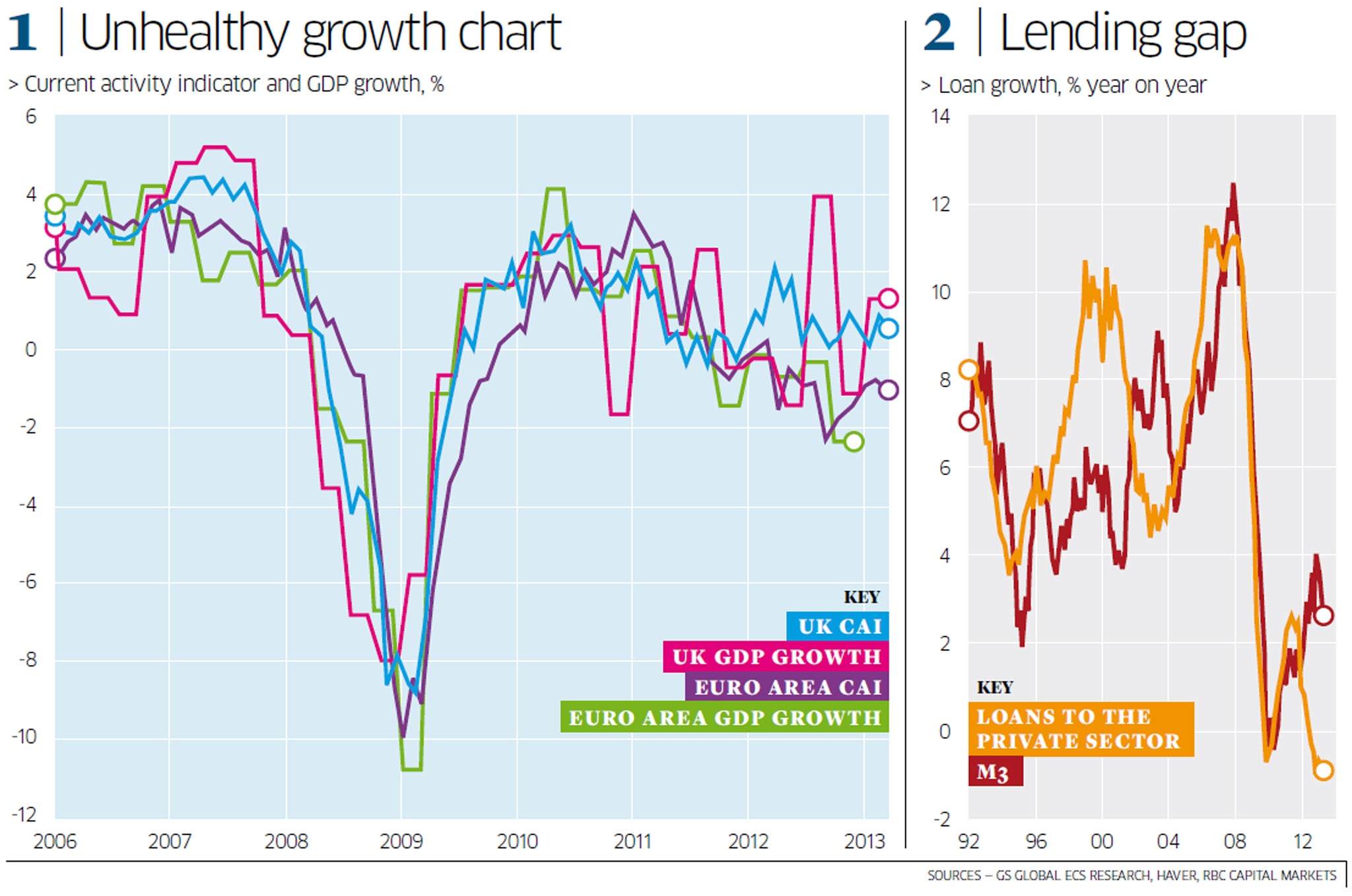

Part of the problem in Europe is that money supply is going up but lending to businesses is going down. You can see a snapshot of that divergence in the small graph. It is a familiar issue here in the UK. Here as there, it is hard to know to what extent weak lending is mainly the result of lack of demand for loans or lack of supply from the banks.

It must be a bit of both but if it were mainly lack of demand, then increasing the supply will have little impact. As for the price of loans, as opposed to their availability, when ECB interest rates are only 0.75 per cent, it strains belief that a 0.25 per cent cut – even if it fed through to a fall in the average interest rate on a loan – will affect demand.

Still, the ECB has to be seen to be doing something, and it is hard to see how a cut in rates, presumably associated with some other measures to increase loan flow, could do any harm. Indeed, given where Europe is now, with lending to the private sector having contracted for 11 months on the trot, even a modest boost would be more than welcome.

That leads to the wider issue, the power of central banks. The ECB has over the past 18 months demonstrated both how powerful and how weak a central bank can be.

We saw the power last year when a threat to buy the sovereign bonds of the distressed eurozone countries flipped round the markets and enabled Italy and Spain to start borrowing from them again. As it turned out, the ECB did not have to do anything; the threat was enough. The reason is simply that a central bank has almost infinite ability to print more of its own money, and so no one in the markets will want to bet against it. When Mario Draghi said that he would do "whatever it takes" to save the euro, market-makers took heed.

But we have also seen the limits of power. Central banks can print the money but, as we have seen, they cannot make the banks lend it on. We are only gradually learning both how quantitative easing affects the real economy, on the benefit side and on the cost side. Unprecedented monetary easing in the US (or at least unprecedented in peacetime) has not led to much of an increase in US employment, which is still below its previous peak. In the UK, it has not led to a strong economic recovery, even allowing for the official growth figures understating what has actually been happening. In Europe, it has not stopped the present dip back into recession. Of course, we cannot know what would have happened had the central banks not adopted QE – but I think it is pretty clear the situation would be far worse. So how bad is it for Europe?

In the large graph, you can see the official figures for growth in the UK and the eurozone, together with a "current activity indicator" developed by Goldman Sachs. The latter seeks to give a more timely and more accurate tally of economic activity. Activity in the UK has just managed to inch forward over the past two years, and now is consistent with growth running at about 0.5 per cent a year. That is not great, but remember that it is pulled down by the decline in North Sea output. Onshore activity is higher, with the Centre for Economics and Business Research estimating that it is running closer to 1 per cent a year, again not great.

Activity in the eurozone, as measured by the current activity indicator, has been negative since the beginning of last year, and remains so. The present consensus seems to be that growth overall will resume towards the end of this year but I think it will need some major shift in confidence, and I am not sure where that will come from.

That brings things back to the power of central banks. As far as Europe is concerned, in the absence of political union or even effective political co-operation, the ECB is really the only point of power. So the big question this week seems to me to be whether it can lift the confidence, particularly of the business community but also of consumers, towards the expectation of some growth. Can it do for confidence in the eurozone economy what it did last year for confidence in the survival of the euro?

It is a tall order, and the odds are stacked against it. But it is very much in UK self-interest that the ECB gets a good response to whatever it decides to do on Thursday.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments