Hamish McRae: Unemployment and GDP figures are still a riddle

Economic View: There is a real risk that the Bank of England will make some serious policy errors in the coming months

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It is more of the same – but with a twist. I'll come to the twist in a moment; first, a word about the continuing puzzle as to what is really happening to the British economy.

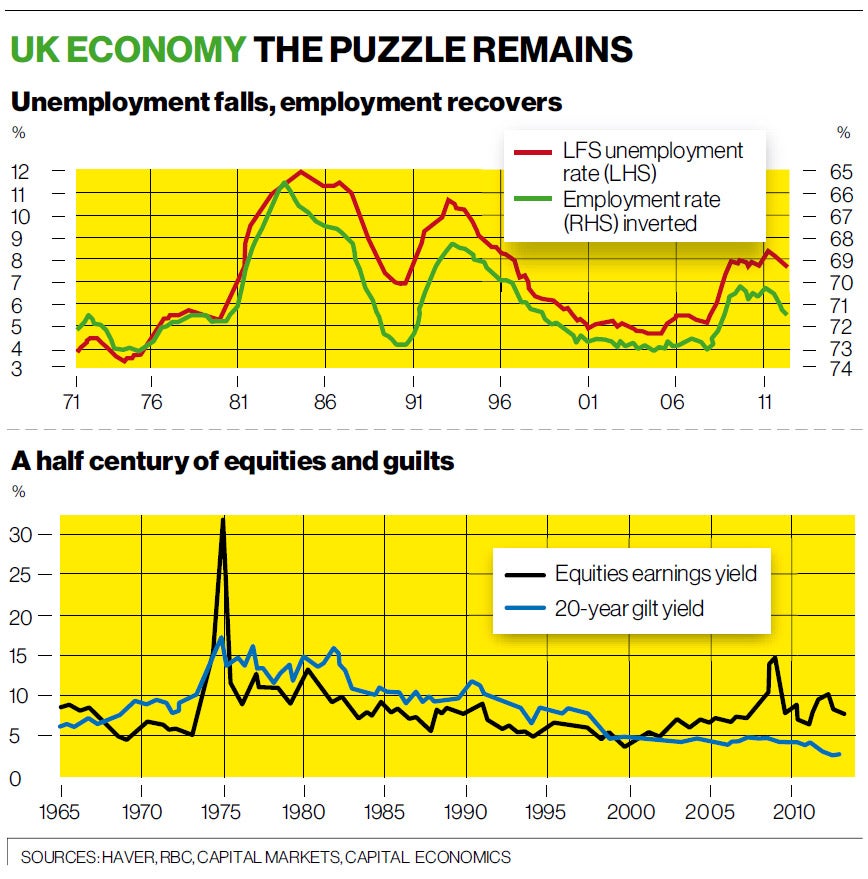

The story is the familiar one of a contrast between the labour market and the published gross domestic product (GDP) figures. The former suggests the economy is booming; the latter that it is stagnant. The latest labour market statistics show an economy with over half a million more people in work than a year earlier, of which 394,000 are full-time jobs. It is true that unemployment remains stuck at a little under 8 per cent (top graph), but what seems to be happening is that the UK is sucking in workers from the rest of Europe and as a result our unemployment numbers are not coming down as fast as they should.

On the other hand the published GDP figures show an economy that grew just 0.1 per cent last year, and while those will be revised they will have to be changed by a huge amount to explain the discrepancy. So the puzzle remains. The knee-jerk reaction to this is to say there has been a decline in productivity, with more people needed to produce the same output. But that is not really an explanation because the productivity figures are calculated as a residual. The statisticians take the notional output and divide it by the number of hours worked and that produces the decline in productivity. It is only correct if the GDP and employment numbers are correct – and there are a lot of reasons to think they are not.

In a few years' time it will all be much clearer, but meanwhile we will just have to live with the data we have got and apply a bit of common sense to it. Those of us who think that the economy is indeed growing, albeit slowly, can take comfort from the car registration figures, which were up again in January and are some 11 per cent higher than a year ago. The car is the largest single consumer purchase as well as being an important company investment – roughly half of new cars are bought by companies – so that would suggest some sort of recovery is under way. But it is not a great one: there is still a big squeeze on pay, which is rising at less than 2 per cent a year and seems to be stuck there.

So what is the implication for policy? We will get some more data today on the Government's accounts for January. These are particularly important because January is the biggest month for tax receipts, with self-assessed income tax coming in. Personally, I expect they will be quite weak, for many high-earners have been cutting their income or having it cut for them, and the Government will struggle to meet its fiscal target. The harder it is to meet the target, the longer the fiscal squeeze will continue. The longer the fiscal squeeze the longer a loose monetary policy will continue. And that brings us to the twist.

The headline was that the Bank of England's Governor, Sir Mervyn King, had voted for more quantitative easing, and though outvoted and with his retirement less than three months away, the perception has taken hold that one way or another the Bank will do whatever it takes to boost growth. If that means higher inflation, so be it. Sterling fell sharply as a result. Gilts fell too, with 10-year gilts now yielding more than 2.2 per cent, having dipped briefly below 1.5 per cent last summer.

My own reaction to all this is that it is too early to think that British monetary policy will give up on inflation, but there is a real risk that the Bank of England will make some serious policy errors in the coming months. The danger is that it will attempt to give an even larger short-term boost to demand but that this will have the perverse effect of increasing inflationary expectations, increasing long-term interest rates and – at worst – leading to a run on the pound. Savers will be clobbered and there will be a scramble to get out of cash and into anything that gives protection against inflation. We are not yet back to the situation of the 1960s and we may never get there, but there are certainly some uncomfortable parallels.

Have a look at the bottom graph. It shows gilt and equity yields since 1965. At the beginning of the period, 20-year yields were around 6 per cent, as people saw that inflation was rising, the pound was likely to be devalued, and though inflation was around 3 per cent, they needed some compensation for the risks. Their worst fears proved right. Sterling was devalued, inflation did indeed climb, and gilt yields hit 17 per cent in 1975. There was a scramble to get money into anything that might protect its value. Gold gave protection, property gave protection and equities gave some protection, though you had to get the timing right. The collapse of share prices at the end of 1974 is shown by the peak in the equity earnings yield.

Now look at where markets stand at the moment. As far as equities are concerned, 1974/5 was the aberration and the yield now is pretty much in the normal range. But as far as gilts are concerned, the aberration is now. The UK long-term interest rate last summer was lower than at any time since 1965. Actually it was lower than at any time since the founding of the Bank of England in 1694. Yields have come up since last summer but they are still unsustainably low.

We have not yet had the desperate scramble to get out of cash which happened progressively during the 1960s and 1970s but maybe the surge in share prices shows investors are starting to fear that the Bank of England, and indeed other central banks, might lose control of inflation, as they did in the 1960s and 1970s. The slippery slope beckons.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments