Hamish McRae: Unconventional measures that leave us all with a mess to clear up

Economic Life

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It is quite hard to get one's head around it all. If anyone had said last summer, when base rates were 5 per cent, that they would be down to 0.5 per cent it would have seemed mad. But it would also have seemed beyond all reason that the annual increase in the retail price index, which reached 5 per cent then, should now be near zero and will almost certainly soon go negative.

If that is hard, the idea of the Bank of England doing the Zimbabwe option of "printing money" would have seemed shocking – and that this decision should be met with general acclaim, well, let's not think about that just yet.

Last summer the economy still was cantering on. House prices were falling fast but share prices were quite resilient, consumption was still rising, overall economic activity was close to its all-time peak and the pound was still riding high. Actually the economy was about to head over a cliff but it did not feel like it – just as the Warner Brothers' Wile E. Coyote would head over a cliff (as the Roadrunner screeched to a halt just in time), carry on in mid-air, and only fall to the ground when he looked down and saw there was nothing below.

That was the situation last summer and monetary policy was set to be appropriate for conditions then. You can have a debate as to whether the Bank of England should have been more anticipatory in its actions and cut rates earlier but I can't see that doing more than helping at the margin. Every economy in the world was heading off a cliff at about the same time.

Since then monetary policy has become spectacularly easy. Interest rates have been slashed in the US and somewhat more slowly in Europe as well as here. But the central banks have, in Lord Keynes's analogy, been pushing on a string: they ease policy but nothing happens.

Nothing happens for five main reasons. First, cutting official rates only partially feeds through into lower borrowing rates and actually lowers deposit rates for savers. Second, rates may come down but if banks' capital is stretched they may not be able to increase their lending. Third, as the economy slows and asset prices decline, many would-be borrowers may not be credit-worthy. Fourth, you cannot cut interest rates below zero and if prices start to fall real interest rates may remain elevated even with very low nominal rates. And finally if they completely lose confidence borrowers may not want to borrow at any rate.

So if cutting the cost of money is not enough, you have to increase the supply of the stuff, hence the measures announced yesterday. It is not quite a matter of printing more money, but it is creating more artificially, hence the shorthand expression. We don't have to print more of it (though we may find ourselves doing this) because we have a functioning central bank and a sophisticated banking system. Zimbabwe does not: hence it resorts to the printing presses.

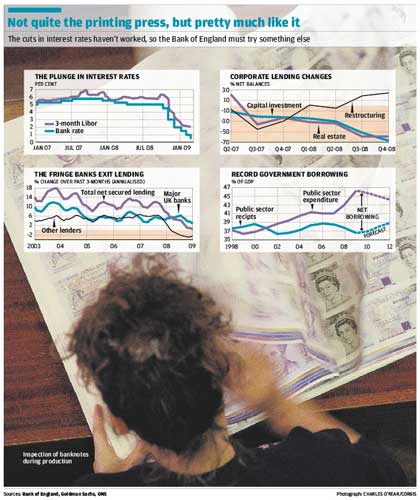

What will happen? To be honest, I don't think anyone knows but the graphs may help explain why it is probably necessary to resort to such tactics. You can see the plunge in interest rates at the top left, with the three-month money market rate following the fall in official rates but not tracking it as closely as it did before the credit crunch. So there is already a problem. Actually it is worse than that, as this merely shows the formal money market rate, but since banks are very reluctant to lend to each other at any rate, the fall in rates has not eased credit supply.

It gets worse. On the top right graph you can see how the nature of lending to companies has shifted. Instead of lending going to support investment and property it has moved towards restructuring. So voluntary borrowing – companies borrowing for expansion of some sort – has been replaced by involuntary borrowing – borrowing for survival. It is almost as if banks have to use whatever funds they have available to support companies that might otherwise go under, rather than lend to finance expansion.

It gets worse still. As you can see from the bottom left graph, overall lending growth, the purple line, has fallen to zero. But major British banks (blue line) have kept increasing their lending right through the downturn. By contrast the fringe banks, a lot of them foreign ones, have actually withdrawn funds from the market, as the black line shows. So our mainstream banks have to boost their lending by a large amount, taking on the load shed by the others. No wonder credit is tight. No wonder the Bank has to go unconventional.

Because the Bank has never done this before, which ought to make us all feel uneasy, we don't know what will happen. The immediate reaction in the markets was that this will take pressure off the gilt market, by making it easier for the Government to fund its deficit. I am not sure that will turn out to be true in the long term but it may help in the short.

The problem is mind-blowing, as the final graph shows. The Government has to find 10 per cent of GDP. That is £140bn. And it has to do so each year. Where will the money come from? There are not the savings in the country to do it. Before the programme was announced yesterday the Bank had held a gilt auction for long-term debt. It just about cleared and it got the money, but it was a nervous one. Yesterday, gilt prices soared. Does this mean the market thinks that this will be the Government's get-out-of-jail card?

I simply don't know and would not trust anything I am told. What does disturb me is that if the Government is funding itself largely from genuine savings, those savings will not be available to finance other things. It stands to reason that if we savers put money in national savings those savings are not in our building society or bank. One of the disturbing things that is happening now is the way people are withdrawing their money from the mainstream banks for the reason that they pay such dreadful rates.

That brings me to a final point. Savers matter. There are more savers than borrowers. Many older people have seen their incomes savaged by the plunge in interest rates. It may be right in the short term to cut rates to boost the economy but it is socially divisive, hitting people who are least able to fight back. It is also a terrible signal to would-be savers, and the one absolute certainty is that the country has to increase its savings rate in the years ahead. Borrowers matter; but savers matter too.

So the test of all this will be how quickly interest rates get back to normal levels and how quickly the unconventional measures are reversed. We are doing things now the country has never done before, certainly in peacetime, and there is no clear indication of the path back. The financial mess that the next government – and the one after that because this won't be just a four-year job – will have to clear up looks more frightening by the day.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments