Hamish McRae: UK must meet challenge of a rising population for the economy's sake

Can the South-east stay an attractive place to live if it has to fit in, say, 10 million more people?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.So we have to fit in nearly another half-million people into the country every year. Last year the population rose by 419,000 and this upward climb – mostly from a higher birth rate, partly from net immigration – seems to be climbing. There were more babies born in the UK last year than at any time since 1972 and that trend seems likely to continue.

Of all the drivers of economic growth demography is probably the most important. It helps determine the size of the workforce as well, naturally, as the size of the "dependents", the young people and retired whom that workforce has to support. That in turn is a key determinant of the size of the economy, for other things being equal, the bigger the workforce the bigger the economy. More people produce more goods and services but they buy more stuff too.

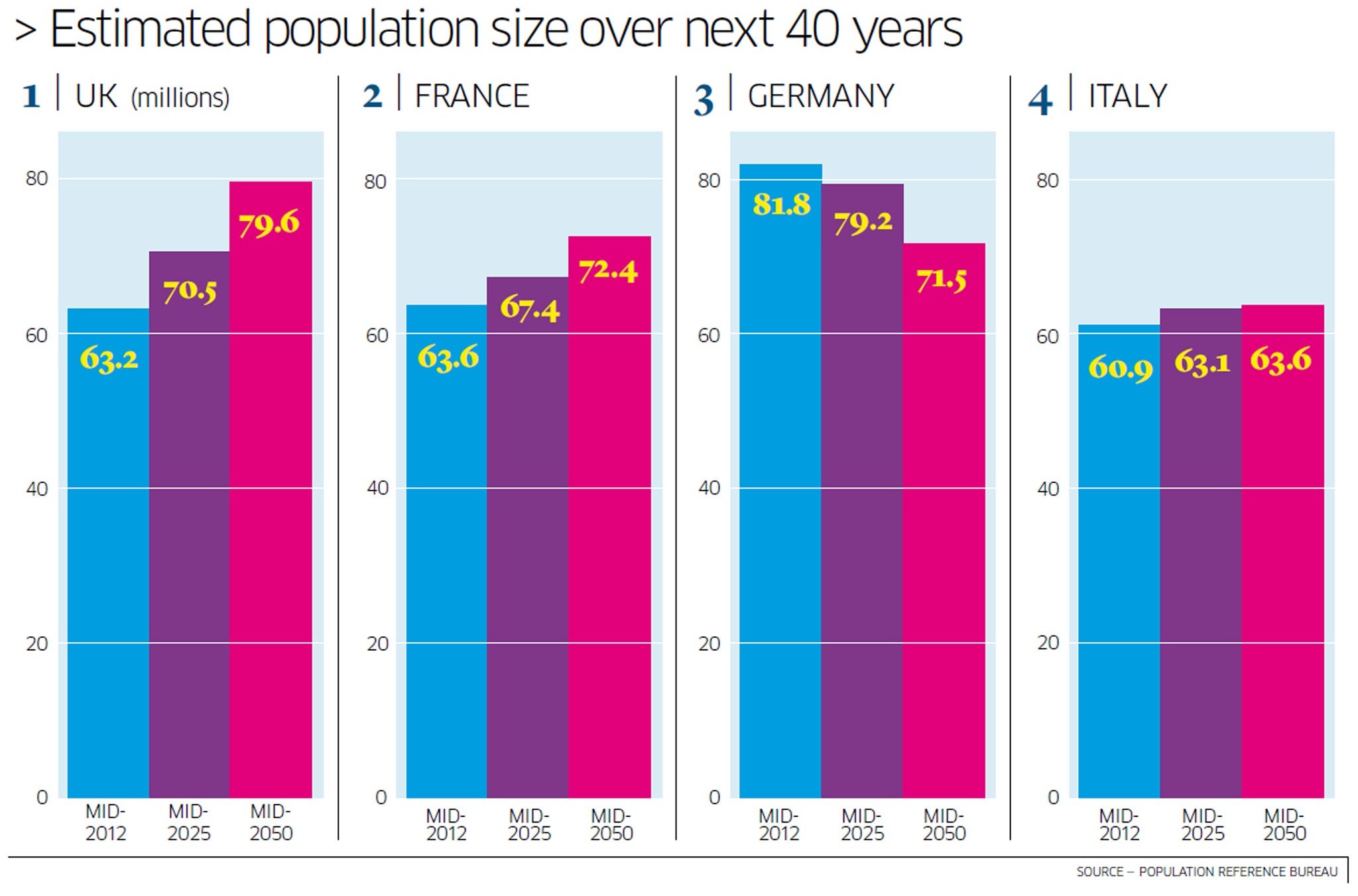

To give some feeling for what is going on I have put in the graph the present size of the population of the four largest European economies, plus some projections for 2025 and 2050.

These will not be right as to detail, for such projections never are. Indeed the estimate there for the UK's population in the middle of last year, 63.2 million, may already be an underestimate for last week's figures from the Office for National Statistics suggest that it was 63.7 million. But they are broadly plausible and form a decent working assumption for what is going on.

As you can see at the moment the UK, France and Italy are roughly the same size while Germany is quite a bit bigger. Run forward to 2025 and the UK has pulled clearly ahead of France and Italy but is still smaller than Germany. Head on another 25 years and the UK is the largest European country by population and by a fair margin. We on the way up, pass Germany on the way down sometime around 2040. That does not necessarily mean that we would have a larger economy than Germany by then but the balance of probability is that we will.

Looked at in a global context these changes are quite small. For example the fact that India is likely to pass China as the world's most populous country in about ten years time dwarfs these modest population shifts within Europe. Nigeria is projected to top 400 million by 2050; Pakistan will be well over 300 million. By contrast Japan will decline from its present 127 million to 95 million. But from our own narrow perspective there are some obvious consequences.

One would be the rebalancing of Europe. We cannot possibly see the political shape of Europe in 2050, any more than one could have seen what it might be like in 1950 from the viewpoint of 1913.

We just have to hope that nothing as ghastly as the first half of the last century will happen again. But we do have to ask what the EU would look like were the UK to be both the most populous country and the largest economy. Indeed – and I do find this striking – even if Scotland were to leave the union, the remaining parts of the UK would still be the most populous European nation.

It would certainly be a different Europe, but it would also be a different Britain. One-quarter of the babies born in the UK at the moment are to mothers born abroad (think of Nick Clegg's children), while one-third have a parent born abroad. So already we are becoming more like the US, in that being British is for many people the result of a choice made by their parents to move to the UK.

But I think the question that most people will find hardest to get their minds round is this: how do we fit these extra people in? It is a question made all the sharper by the fact that the fastest growth of population is to the south-east of a line between the Severn and the Humber, with the fastest growth of all being in London itself.

People will react in different ways to all this but from an economic perspective these population movements are in fair measure a reflection of economic success. People migrate to a place because there are jobs there. If this creates problems, these are nothing to the problems of a declining population. Think of Detroit, or some of the medium-sized cities of Japan, where schools are shutting because there are no children and the old are looking after the very old.

So can the South-east corner of England remain an attractive place to live if it has to fit in, say, another 10 million people?

If you look at numbers it should be possible. London's population of 8.3 million is still below its peak of 8.6 million in 1939 but in another five years we should be past it.

The wider agglomeration is well past its previous peak. Yet the population density on London and indeed the UK is not that high. Inner London is about half the density of Paris or New York, and while the total urban area of New York is less dense, that of Paris is more so.

The UK's population density is lower than that of Belgium and the Netherlands, and (maybe a better comparison) Japan. It is a huge challenge: how do you make somewhere big nice? But it is a challenge that other places have responded to and from which we can learn. It needs sensible investment rather than an ideological approach, but that surely should not be beyond us.

Besides, what's the alternative? If we run a successful economy, people will come. So we have to make it nice for them. Do we really want a less successful economy? We have had a bit of experience of that and that was not a bundle of fun either.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments