Hamish McRae: Two takes on health of the labour market – and both could be right

Economic View: Demand for labour is very uneven across the country and across skills

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Britain's job-creation machine is still cantering onwards. Another set of decent labour market figures was enough to nudge the pound back to $1.58 and keep the 10-year gilt yield at 3 per cent. The private sector continues to create three new jobs for every one lost in the public sector, which is encouraging, but wages are still dropping in real terms, which is not encouraging – or at least not in the sense that living standards are still stagnant.

All this is pretty much as expected. If people were surprised, they were not paying attention, for since the economy has continued to create some jobs right through an uneven recovery, it would be odd if it did not create rather more when the economy picked up more pace.

So that is where we are; what happens next? The unemployment rate has taken on extra significance as a 7 per cent level has been elevated as a trigger for interest rate cuts. (Mark Carney, the Bank of England Governor, did not quite make it as explicit as that, but that is the main message.) There has therefore been a string of estimates as to when unemployment might fall to that level, and this "unexpected" decline to 7.7 per cent naturally brings that magic number closer.

But behind this narrow debate, important for the money markets but narrow nonetheless, is a wider and more interesting one. This is about what is really happening to the UK labour market. The thing that has astounded almost all economists, even relatively positive ones, has been the way employment held up through the downturn. In terms of published GDP, this has been the weakest recovery since the Second World War; in terms of employment, it has been the strongest. We are, according to the figures, still 3 or 4 percentage points off the peak, but we have substantially more jobs than ever before.

The conventional explanation for that is to say there has been a sharp fall in productivity, but that is not really an explanation at all – for productivity is calculated as a residual. It is the number that pops out when you put all the other figures in. My own guess, and it is only a guess, is that the explanation is a combination of two factors.

One is that we are now undercounting activity in the service industries, but we overcounted it at the top of the boom. (How do you measure the output of a highly paid but unutterably foolish banker who makes duff loans?) So the fall in output was not as big as published because the peak was not as high as we thought, but output now has recovered more than the figures suggest.

The other is that there is indeed quite a lot of slack, particularly in the service industries, as employers have cut their costs by trimming wages and hours but tried to retain staff so they could quickly boost output if demand warranted it.

The first would explain some of the puzzle but not all of it. The second is what matters now. Demand is clearly rising quite swiftly, at around 3 per cent annual rate, which is quite a bit faster than the trend growth of the economy of 2-2.5 per cent. If this swifter growth continues, it should mop up spare labour. But maybe employers in the service industries are set to meet much of the increase by boosting the hours of their existing workforce, perhaps by asking part-timers and people on contract to work a slightly longer week.

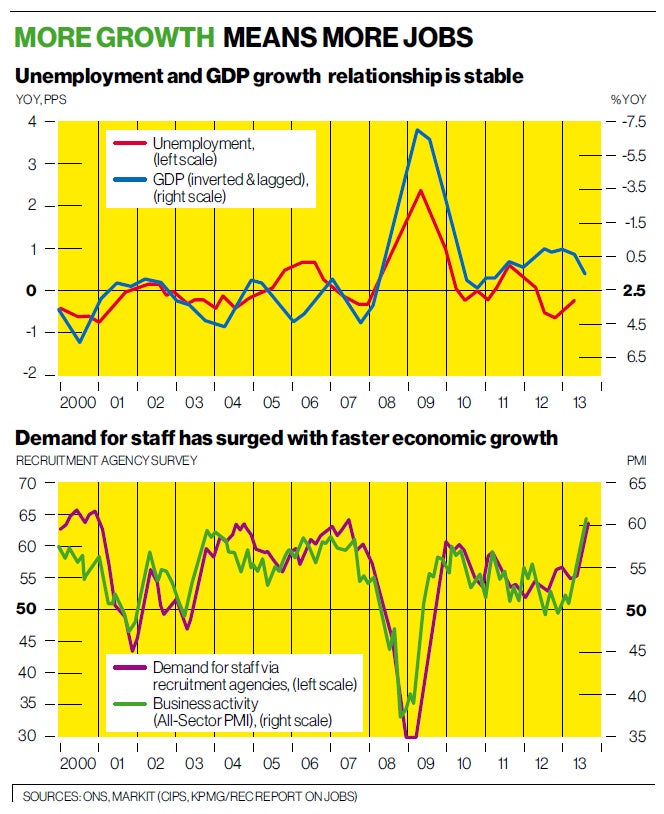

We simply don't know, but we can make some guesses. If you look at the top graph, you can see changes in unemployment plotted against changes in GDP. In other words, the peak rise in unemployment in 2009 was just over two percentage points (red line), which coincides with a 6 per cent fall in GDP (blue line). Kevin Daly of Goldman Sachs, who did this work, concludes that though there has been some divergence between the two lines in the past couple of years – ie we have created more jobs than you might expect despite slow growth – the two broadly do fit together. He reckons that even with faster growth, it will take quite a while to pull unemployment down to 7 per cent.

A somewhat differently nuanced view comes from Chris Williamson at Markit, the researchers. The bottom graph plots business activity as signalled by purchasing managers' indices alongside demand for staff as reported by the recruitment agencies. In both cases, anything above 50 signals expansion, anything below contraction. What is striking here is the surge in demand for staff, which closely tracks the rising optimism of employers more generally.

The conclusion you would draw from the top graph is that there is still a lot of slack in the job market. The conclusion from the bottom one is that demand for labour is already climbing fast. Which is right?

Well, they both are in that they reflect different aspects of a hugely complex, changing economy. We work in quite different ways from five or 10 years ago. There is much more self-employment, there are many more young immigrant workers from the Continent, more retirees still at work, more part-timers, more contract workers, and so on. Demand for labour is very uneven across the country and across skills – more uneven than it was a decade ago.

But if both are right, which is more useful as a guide to the trend of unemployment in the future? Actually we won't have much of a feeling for several months but I think by the end of this year we will begin to see the steady fall in unemployment that would justify the financial markets' expectation of a rise in interest rates either late in 2014 or early in 2015.

But whatever the timing of that, the creation of more jobs cannot be bad news.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments