Hamish McRae: The US oil boom is helping to power global growth but we don’t know how sustainable it will be

Economic View: Falling energy prices boost growth in consuming countries. We can feel that here in the UK

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Saudi Arabia has just told Opec that it is cutting its oil production – a response to the Brent price dipping below $95 a barrel. That is the lowest for two years and, importantly, below the $95-to-$100 range that was described as fair by the Saudi Oil Minister, Ali al-Naimi, at Opec in June. So Saudi Arabia is fulfilling its long-established role as the swing producer for Opec, increasing output when demand rises and cutting when it falls. This has not always worked, for there have, of course, been surges and slumps in the oil price over the past couple of decades but the world’s biggest oil producer has long sought to be highly responsible in its production policy.

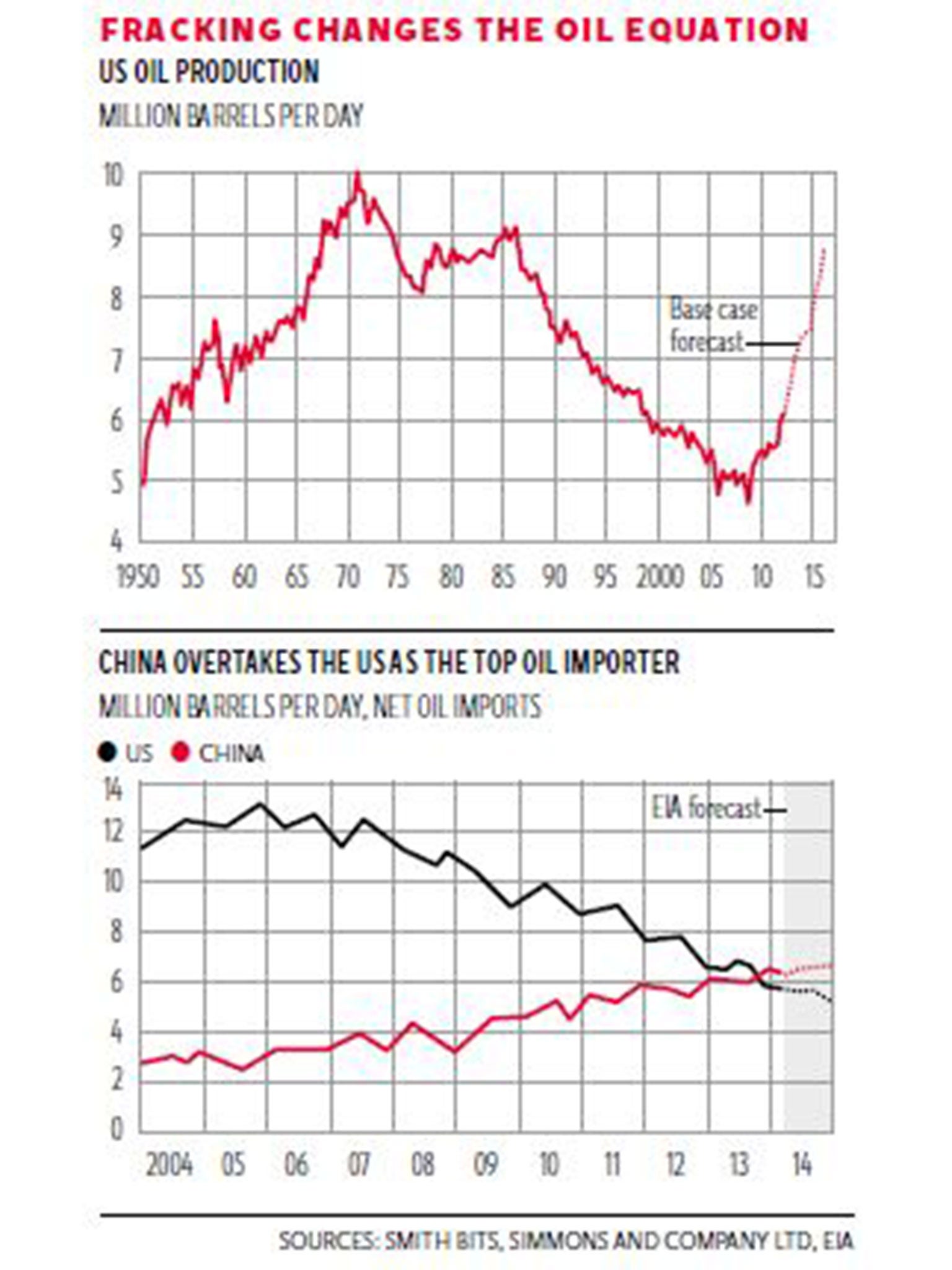

This time, however, there is a difference, not in Saudi policy but in the underlying market equation. For a start, while Saudi Arabia is still the largest producer, it is only just the largest. It looks as though the United States will pass it in the next couple of years. It is just possible that the tipping point has occurred this year but we will have to wait and see. Next, thanks to rising domestic production, the US is importing less and less oil. Indeed, it may already have been passed by China, where imports keep on climbing, and if so that would be another tipping point. You can catch a feeling for both trends in the graphs.

This shift in the market, a shift in power as well as in hard cash, will have profound geopolitical effects. The US becomes more powerful in the sense that it will be less reliant on global markets for its energy supplies. Opec as a whole, and Saudi within Opec, remains hugely important, but not quite as important as it was even a couple of years ago. By cutting production, the Saudis have helped to stabilise the oil market for now, and the Brent price perked up a bit on the news. But if the US does manage to become the world’s largest oil producer, its own leverage over the market correspondingly increases.

There are two other things to note. On the supply side, right now, production in Libya is disrupted; production in Iraq is disrupted; production in Iran is disrupted. So three huge producers are pumping well below their potential, yet the oil price is soft. And on the demand side, there seems to be some shading down in the growth from China, though the economy there is still growing fast, but demand in the US is solid.

Pull all this together and what should one say? The big message surely is that global oil supplies should be able to sustain decent economic growth for the next few years. Put round the other way, a surge in the oil price is unlikely to occur in the next few years. Since global recessions have frequently been triggered by a surge in the price of energy, one element that might shorten this growth phase of the economic cycle does not seem to be there. That is not to say that the world would ride comfortably through even more serious disruption to oil supplies in the Middle East, still less that this growth phase will go on for ever, because of course it won’t. But if oil prices are coming down at this stage of the economic cycle, it does suggest that the world economy is less vulnerable than many of us thought it might be a couple of years ago.

More immediately, falling energy prices give a boost to growth in the consuming countries. We can feel that here in the UK. The fact that it costs less to fill up the car at the weekend means that there is more money to spend in the supermarket. This is the flip side of the situation at the bottom of the recession. Normally when there is a recession, energy demand falls and the consequent decline in oil and commodity prices helps real demand for other things to recover. Last time round this did not happen, thanks to still-increasing demand from China and the limited increase in supply from the energy producers. Countries that were strong primary producers, notably Canada and Australia, came through the recession in good shape. The rest of us didn’t.

Now we are getting a boost, not at the bottom of the cycle, but once we are already in recovery – or at least most of us are in recovery, for the stagnation in Europe remains alarming. Perversely, lower energy prices exacerbate Europe’s problems by increasing the chance of deflation – falling prices overall. Viewed globally however, lower energy costs must be a benefit. What can go wrong? In the short-term it is hard to see anything. In the medium-term there is a concern, and it would be right to temper any positive commentary on US oil production with a caveat. It is that we don’t know much about the sustainability of the US oil and gas production profile.

It may well be that there is another 15 years of rising production ahead. The thing that has changed everything is fracking. While this is an established technique, dating back more than 50 years, it is only in the past five years that it has been employed on the massive scale sufficient to transform US oil and gas production. What we don’t know, aside from environmental concerns, is how sustainable production will be. Will it fall off faster than production from conventional wells? There is some evidence that it might.

This will not change the picture for the next few years, but it will matter in the future. We simply don’t know enough to be sure. If we cannot even agree how much oil there is left in established fields in the North Sea, we really cannot predict US oil and gas production from new fields in North Dakota with any clarity.

In the meantime, however, cheaper oil – for all the concerns about the effects of added carbon dioxide on the environment – does give a boost to the world economy.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments