Hamish McRae: Tax rises are inevitable – but will need a lot of explaining to voters

Economic Life: Putting the public finances on to a credible basis will be the principle task of the next government

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The economy is getting better; the public finances are getting worse. That is the core message from the latest data on our economy and, while any economic recovery is naturally most welcome, the scale of the fiscal catastrophe is such that the pullout from recession will be longer and more painful than it need have been. History will, I think, come to judge this government very harshly.

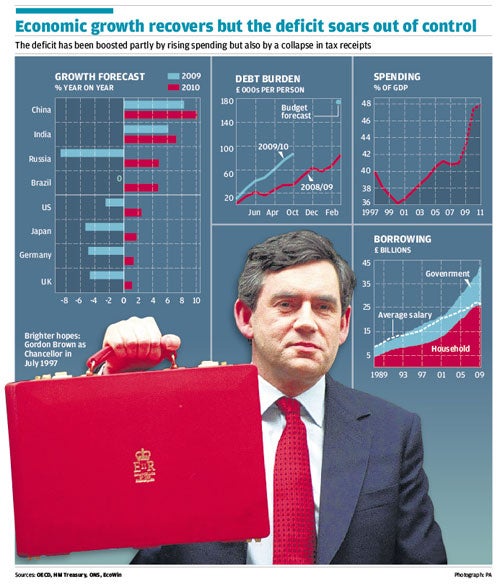

The data first. We have new OECD forecasts for the world economy which, as most of us expected, have substantially upgraded expectations for next year. The UK outlook for 2010 is still a bit low (see the graph, above) but not as absurdly low as it was last time. The big point that emerges from those forecasts, of course, is the astounding contrast between the "old" developed world and the main emerging economies, a contrast that I still think most of us have yet to take on board.

As far as the UK's present position is concerned, the most encouraging new bit of actual news, as opposed to forecasts, was retail sales. These were up 1.1 per cent quarter-on- quarter and 3.4 per cent year-on-year. This squares with rising consumer confidence and the strong sales numbers at John Lewis, and they make it pretty much a done deal that we will show growth in the final quarter of this year. I still think it will eventually be shown that there has been some growth in the third quarter, but it will take some years before the data is in final form and we will know for sure.

The point in the OECD report that took the headlines, however, was not its forecasts but it strictures on the budget deficit. It called for a medium-term plan to do something about the deficit. As every month passes the numbers, I am afraid, get worse and worse. You can see the trajectory of borrowing as it heads towards the target of £175bn this financial year in the next graph, but the bad news is that we seem to be losing ground each month and will probably have a deficit of closer to £200bn.

Since the deficit is the gap between two even larger numbers, it is hard to predict with any precision but for what it is worth, Capital Economics thinks it is on track to hit £220bn, while PricewaterhouseCoopers estimates a more modest £185bn. We will get the official forecast in the pre-Budget report next month but one thing I would put a lot of money on: the new forecast will not be any lower than £175bn – and even that would be stretching credibility.

Credibility. There's the rub. We are running a larger deficit relative to the size of the economy than any other major country. It is larger even than the US, where just yesterday President Barack Obama warned that if country's deficit was not tackled, the US risked a second recession. I think he is right there, because while a modest increase in a government's deficit might in the short-term boost demand, once you get to the sort of levels that we are at now, borrowing even more starts to become counterproductive. People know that it is unsustainable, they know there will be big spending cuts and tax increases and they adjust their behaviour accordingly. We experienced just such a run on confidence in the 1970s, when Labour was last in power, and it was to counter those fears that Gordon Brown introduced his golden rule on borrowing.

As you can see from the next graph, he cut spending as a proportion of output in his first two years as Chancellor, but since then he has presided over a sustained increase in spending without being able to increase tax revenues to pay for it. The tragedy – and it is a personal tragedy for him and well as for the rest of us – has been that he has done exactly what he set out not to do. The young-looking visionary in the photo here, with the newly-made Budget box, has made the very mistake that he desperately did want to make, and we all feared he would.

But in some measure we too are guilty. Have a look at the bottom graph, which shows how total debt per person, that is to say adding household debt and government debt together, was about the same as an average salary until 2001. But since then personal debt shot up so that it is now about the same as the average salary, while total debt, of course, is much higher. It is not only the Government that has gone on a borrowing binge – we have too. The difference now is that we are cutting back our debts, particularly on credit cards, while the Government's borrowing has really taken off. The economics team at ING Bank, which put that graph together, notes that as households continue to cut back their debts, the rate of growth of the economy will be held back too. It is talking about trend growth nearer to 2 per cent per year than the 3 per cent a year of the past decade.

So what happens next as far as economic policy is concerned? It is difficult to divorce economics from politics; obviously, putting public finances on to a credible basis will be the principal task of the next government, and that will be true whatever happens at the election. There is the question of how swiftly to cut the deficit but there is no doubt whatsoever that a start has to be made next year. There will, of course, have to be spending cuts and there will have to be increases in taxation, though how the Government can increase revenues is quite difficult to see.

I have been having a look at these latest figures and there has been an utter collapse in income and corporation tax. Things like VAT are running about 8 per cent lower year-on-year, which is understandable in the context of the cut in VAT. But what are called "taxes on production" – mainly income tax and corporation tax – are down about 16 per cent year-on-year. That is dreadful enough, but what worries me even more is that I cannot see the situation recovering next year. It is pretty clear that the introduction of a top tax rate of 50 per cent will result in a cut in revenues rather than an increase.

Indeed, the weaker-than-expected income tax receipts this year may already reflect people adjusting in advance to that rise. And while some companies are recovering their profitability, most will remain under great pressure. Besides, there is a lagged effect in corporation tax, so revenues will be weak for two or three more years, even assuming a decent economic recovery. The basic point is that taxes for everybody will have to rise and as that happens, people will inevitably have to cut back their spending, thereby undermining the recovery still further.

It will be very hard to explain all this to the voters. It is tough to explain that the problem is not just the recession and the bank bailouts. Even without the bailout of the banking system, the Government's debt would be approaching 50 per cent of GDP and is set to reach 100 per cent of GDP before it can start to decline. It is hard to explain that increasing taxation on high-earners reduces revenue rather than raises it. It is hard to explain that increasing company taxation is likely to cut revenue in the medium term. There is a lot of explaining ahead and it will not be music to the ears.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments