Hamish McRae: Rise in money supply indicates UK growth but can also signal inflation

Economic View: If Help to Buy distorts one section of the economy, QE distorts the whole thing

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Is there really a bubble? Well, clearly not yet, but the past few days have seen one government policy, the Help to Buy homes scheme, raising increasing doubts. Is it really such a good idea? Like all economic interventions it carries costs and you can argue as to whether these are acceptable or not. But there is a bigger issue here, and that is whether the costs of quantitative easing (QE) are starting to exceed the benefits, and this is something that we are likely to hear a great deal more about in the months to come. If Help to Buy distorts one section of the economy, QE distorts the whole thing.

The costs of QE are hard to distinguish, partly because we have no previous experience in peacetime of such a policy, partly because it is hard to separate the impact of QE from that of near-zero interest rates, and partly because the costs of both will take many years to become fully apparent. So in making any sort of tally it makes more sense to bundle the two aspects of ultra-loose monetary policy together. Where to begin?

Well, it probably makes most sense to look first at deleveraging, the extent to which we have got our household balance sheets under control, for making it easier for us to do that was one of the prime objectives of the policy. Cheap money makes it easier to cope with high debts.

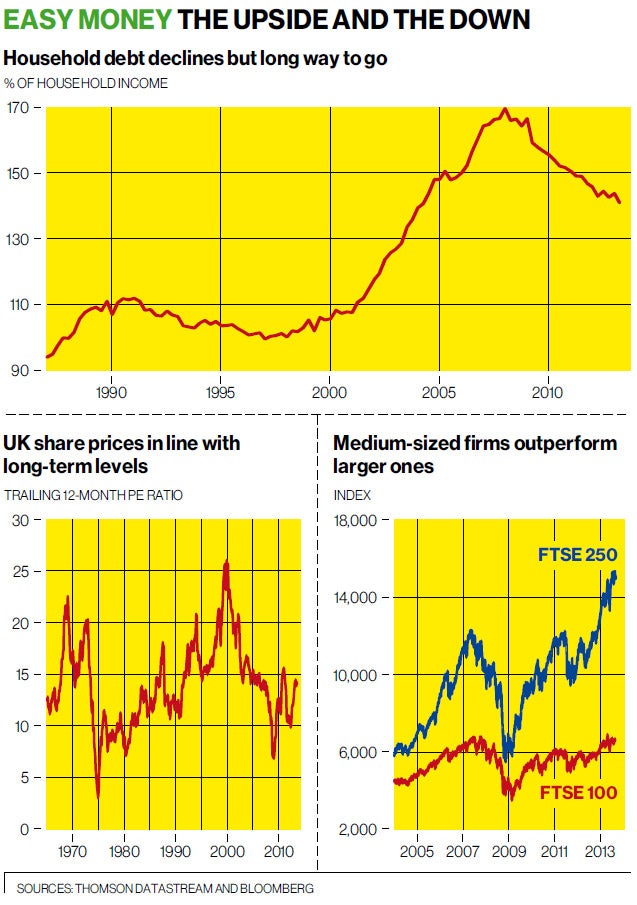

The Government has yet to begin to pay back its debts, and is at present merely adding to them at a somewhat slower level. But we as individuals have not done too badly at all. People are still paying down mortgages, the reverse of the equity-takeout that characterised the boom years. As you can see from the top graph, household debt relative to income is back down to about the same level as in 2004, though there is a long way to go before we are back to the more comfortable level of the late 1990s. Incidentally, if you are wondering why living standards are not rising now, that graph gives a pretty good explanation: we supported that huge rise in living standards by borrowing far too much. Both governments and people made the same mistake of over-borrowing, but we have corrected much faster.

Another positive effect has been buffering the fall in house prices, though there are longer-term costs to that. Prices are nearly back to their previous peak, though there are great regional differences. They are higher in the south-east (and much higher in prime London) but still lower elsewhere. Overall, though, they still look rather high relative to incomes, at about six times earnings against a post-war average of between four or five times. Capital Economics, which has just done some work on this, thinks that it is premature to worry about a bubble in house prices, and that seems a sensible judgement.

Against these broadly positive outcomes are several negative ones. Obviously income for savers has been cut. Income from interest received by UK households has almost halved between 2007 and 2012, falling from £43bn to £22bn. True, it had risen sharply in the years before that, but halving the income of someone who has done nothing wrong is a pretty savage punishment.

Arguably it is worse, because not only have unsophisticated savers been hammered. More savvy owners of assets have been rewarded, for share prices have risen, and the share prices of smaller companies have risen faster than those of large ones. You can see that in the bottom right-hand graph.

Overall, the market is just about back to its peak of 2007, though the FTSE 100 index is still well below its all-time peak of 31 December 1999. But the FTSE 250 index is well up on 2007, reflecting perhaps that these companies are more tied to the British market, as opposed to the global market, and therefore have benefited more from easy money policies.

Overall, share prices are fairly valued, as you can see from the left-hand graph, with a trailing price/earnings ratio of just below 15.

So you could say that there is, as yet, no overall bubble in shares and you can justify the policy on those grounds. But there can be little doubt that one effect of easy money has been to push all asset prices higher than they would otherwise have been. So this is a policy that favours holders of assets, i.e. the rich. You could argue that by encouraging people to take money out of bank deposits and invest in shares that this boosts enterprise by improving companies' access to capital and in a way it does. But most savers would find this difficult to do – not everyone has a friendly stockbroker – so this highlights the way in which there is a premium on financial sophistication.

Up to now, however, you can argue that these adverse side-effects of very easy money are acceptable – the lesser of two evils.

The tipping point will come when easy money affects inflation in a serious way. It hasn't yet. Maybe part of the explanation for the UK's poor inflation record is monetary policy, but it is not easy to see the links. Sterling has recovered quite well, so we are no longer importing inflation in the form of higher import prices.

Much of the problem has been high administered prices (the environmental charges on energy, university fees and so on), which cannot be blamed in the Bank of England.

However, the money supply, narrowly defined, has been shooting up recently, which is a good indicator of solid growth through to next spring, but which may also signal an inflation warning.

If you spray money around as we have done, it ends up somewhere – eventually in higher prices. That, in turn, must mean the end of ultra-cheap money.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments