Hamish McRae: OK, we're recovering – but these figures seem too good to be true

Economic View

The mood has certainly flipped, but has the reality? Well, see what you think. When we headed into the recession there was an inevitable spate of speculation about its likely characteristics. Would it be a V, with a sharp recovery, or maybe a W? Pessimists thought it might be an L, and on some of the published data at least there seemed to be elements of that. But in the past few days it has been looking more like a U: a sharp fall, a long period of weak demand, then eventually a sharp recovery.

Some of us have argued that the economy has been adding pace since the middle of last year and the dismal GDP figures were failing to pick this up. We can take some comfort both from the revisions that have started to come through but more from the hard data about car sales, housing activity and the like, which have been positive for many months. The people who peddled that "triple-dip" stuff have been proved quite wrong. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which was absurdly gloomy about the UK economy earlier this year, has done a sharp about-turn with its latest forecasts.

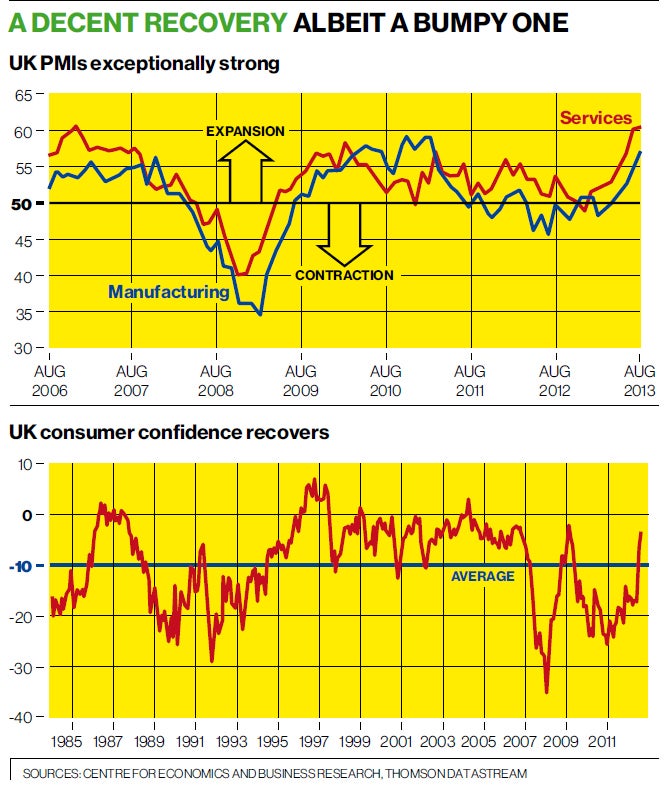

But now the data seems to be almost too good. Second-quarter growth was revised up to 0.7 per cent, an annual rate approaching 3 per cent, and there is talk of the third quarter being 1 per cent, an annual rate of 4 per cent. That would be pretty stunning. True, the purchasing managers' indices are very strong (see first graph), and true, consumer confidence has bounced up (second one). But common sense tells us that you don't go from a slow-growing economy to a booming one in a few weeks, which makes me a little cautious about this shift of mood. It feels to me more as though the economy is gradually strengthening, rather than achieving some sudden take-off.

Actually this is better – better because a gradual broadening of the recovery is more likely to be sustainable than an artificially driven spurt. But we need to recognise that behind the present recovery there are some serious weaknesses – things that need to be fixed during the period of growth.

The most obvious is the fiscal position. We are still running a deficit of some 7 per cent of GDP; the US is now down to little more than 4 per cent. (As Doug McWilliams of CEBR notes in a report of a five-week tour of the States, the US has cut its deficit more in one year than we have in five.) I take from this that we could be cutting our deficit rather faster than we are at the moment without grave damage to the economy; indeed, we should be using this growth to slash the deficit quicker, getting back towards the original plan.

The second obvious thing is the need to get back to normal monetary policy: positive real interest rates that reward savers. The new Governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney, has made a troubling mistake by trying to give "forward guidance" on the path of interest rates. By saying that rates would not go up until unemployment came down to 7 per cent, he implied that it would not happen until 2016, maybe 2017. This is simply not being believed. The markets are already pricing the first increase in rates for 2015, with some suggestions it may be next year. If his aim was to hold down longer rates that has failed too. The 10-year gilt yield a month ago was 2.43 per cent; yesterday it was 2.87 per cent. Expect it to tip above 3 per cent in the next few months. Monetary policy de facto is already being tightened.

You can have a debate as to whether forward guidance is a good idea – I happen to think it isn't – but there can be no debate about its effectiveness in practice if the first time you try it people don't believe you.

How could he get this so wrong? I suspect there are two reasons. One was that he was not in touch with what was really happening to the UK economy. He believed the economists at the International Monetary Fund and the OECD, the figures published by the Office for National Statistics, and the views of some politically motivated commentators. He had no intuitive feeling of his own and so failed to pick up on the fact that the economy was actually growing reasonably strongly. Now he is here he will learn whose judgement to trust.

The other reason was the human instinct anyone in a new job has that they should make their mark early on. Adopting the US ideas of forward guidance and an unemployment trigger was an obvious way of doing so. The problem was that he was just a bit too specific. Central bankers are not all-powerful, except in an emergency, and tightening policy is always more tricky (and less popular) than loosening it. Besides, the UK job market is quite different from the US one – we have had a much stronger recovery in employment – so an unemployment target is less apposite.

The bottom line here is that policy will be tightened – is being tightened – and the faster the economy grows the faster that will happen.

There is something else that will have to be fixed during this growth phase. It is a very uneven recovery geographically, focused as it is on London, the South-east and East Anglia. In social and human terms this is deeply disturbing of course. But it is also inefficient in economic terms. This is not a simple North/South thing, because there are pockets of great success outside the South, just as there are pockets of deprivation within it. The trouble is the successful chunks outside the arc of prosperity are not big enough to pull up their hinterlands. We have to use this growth phase to nurture success, wherever it is, and chip away at failure, wherever that is too.

It is a recovery for sure, and that is better than no recovery at all. But is a bumpy and uneven one and will continue to be so.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks