Hamish McRae: India's growth is outpacing China's. What happens next affects us all

Economic View: India's GDP per head is only about one-fifth that of China, so it can grow faster for longer

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

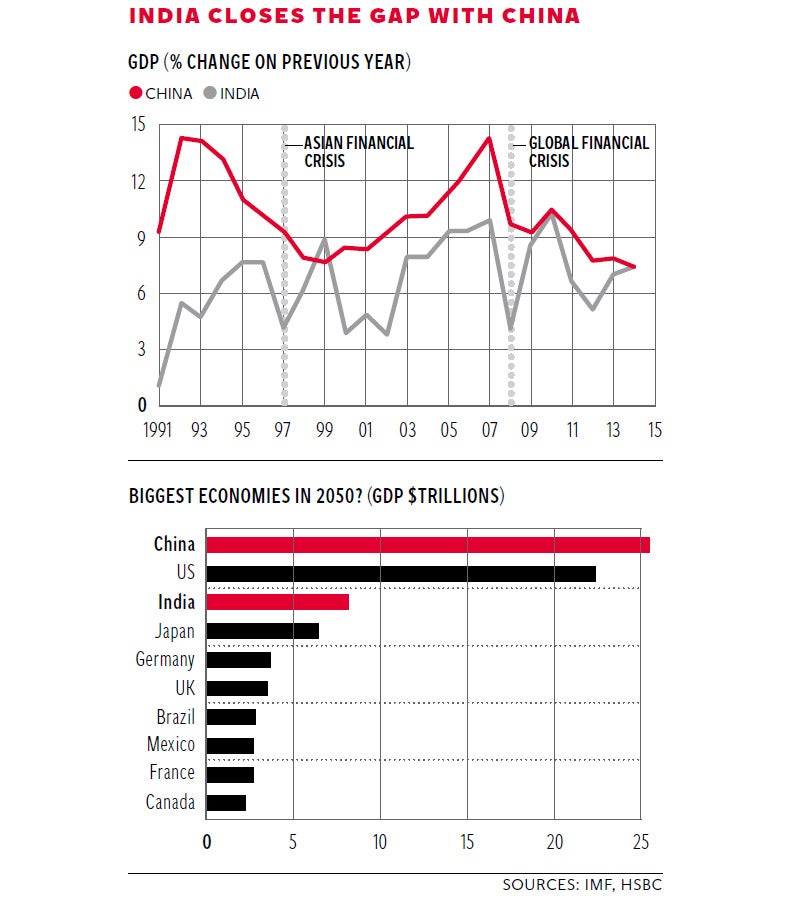

Your support makes all the difference.So India has passed China in the global growth league, with GDP up at 7.5 per cent annual rate in the final quarter of last year vis-à-vis China at 7.4 per cent. This has happened once before, when briefly in 1999 India put on a growth spurt, but the general pattern of the past two decades, as you can see from the first graph, has been for China to outpace India.

People interested in economic history may know that, until 500 years ago, India was actually a larger economy than China and while that is not going to happen in the next 50 years or so, the fact that India is starting to match China in growth rates is of huge historical importance. (It makes whatever is happening in Greece barely register in global significance.) However, there have been false dawns for many countries, when apparent outperformance fizzles away, so the first question is whether India’s growth spurt will be maintained.

In the short term, the answer is probably yes. Both these giant countries face the problems of growth: pressure on infrastructure, pollution, growing inequality and so on. But China faces a greater problem in one regard: debt. It managed to sustain growth despite the downturn in the developed world by increasing investment and hence indebtedness at all levels – state, corporate, financial and personal. But much of the investment, particularly in property, ran ahead of demand. There are a lot of empty apartment blocks. If anything, it has over-invested in infrastructure, not always wisely, though eventually the “build it and they will come” approach may prove valid.

India’s key problems are almost the reverse – more the lack of investment, particularly in infrastructure. But at least the country does not carry the debt load of China, so its growth in the short term at least appears more secure.

If you look further ahead the case for India appears even stronger. One reason for that is population growth. It looks as though India will pass China in total population in about another 10 years’ time. The total fertility rate – the number of babies on average born to each mother – in China is now down to around 1.7, well below replacement rate and actually below that of the US or UK. In India, it is falling fast but is still around 2.7. Population growth does not of itself ensure economic growth, for education and investment are crucial too, but it is a big driver of it.

There is a further and even more important point. The growth of China will inevitably decline as it moves into the middle-income zone. Catch-up is easy, or at least relatively easy. Much, arguably nearly all, Chinese development has come from catch-up, as it has applied technology developed elsewhere. This will not last forever, and there is a raging debate as to whether China is now really developing original technology or is it still pecking around the fringes of stuff that already exists. We should not underplay what China has achieved for one moment. But if you observe what happens when countries reach middle-income status, there is little doubt that growth becomes harder. It is called the middle-income trap, and much of Latin America finds itself in that place.

Now think about India. India has further to catch up, for its GDP per head is only about one-fifth that of China. So it can grow faster for longer. (China only passed India in per capita GDP around 1980.) By 2050, India will still be only approaching middle-income status. It will, however, have become a huge economy.

There are a number of projections about how huge. Goldman Sachs projected in its BRICs report that it would be approaching the size of the United States by 2050, while China would pass the US around 2027. Some other calculations by HSBC suggested a somewhat later passing point for China, some time around 2040. It also showed India further behind the US. But as you can see from the second graph, India is indubitably in third place in global economic size. (By the way, note that the UK is still number six on this projection, still behind Germany but well ahead of France.)

These are just projections, plausible ones, but projections none the less. Whether India does achieve its potential will depend on its policies and the question then becomes whether it will follow growth-oriented objectives over the next generation. There is, as Adam Smith observed, a great deal of ruin in a nation.

I think the best way of approaching that question is to look at what India has achieved notwithstanding sub-optimal economic management. Look at the first graph: solid growth of double that of the developed world for the best part of 20 years. It has now a leader elected for his economic agenda (even if the Delhi voters have rebuffed Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s BJP this week). Surely it would be reasonable to expect some improvement, even if only a modest one, over the performance of the past couple of decades.

There is a further point. Indian technical progress has been remarkable, particularly in the information industries. So it is in the right corner of the commercial forest, a better position perhaps than China. In addition – and this is a generalisation – India seems to be very good at low-cost manufacturing innovation, again maybe ahead of China. All this bodes well.

The big picture remains that of two rising giant economies, gradually eating away at the advantages of the developed world, and gradually becoming developed themselves. It is very hard to see anything changing that. But a narrative that focuses on China seems likely to switch to one that pays much more attention, and respect, to India. If year in, year out through the 2020s India grows faster than China, we in Britain will think of the country differently, as we should.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments