Hamish McRae: Does QE pass the test for all policy initiatives - first, do no harm?

Economic View: The eurozone's lost decade is such a disaster that anything the ECB does should be welcomed

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The European Central Bank will announce its plan for quantitative easing next week, but will it work?

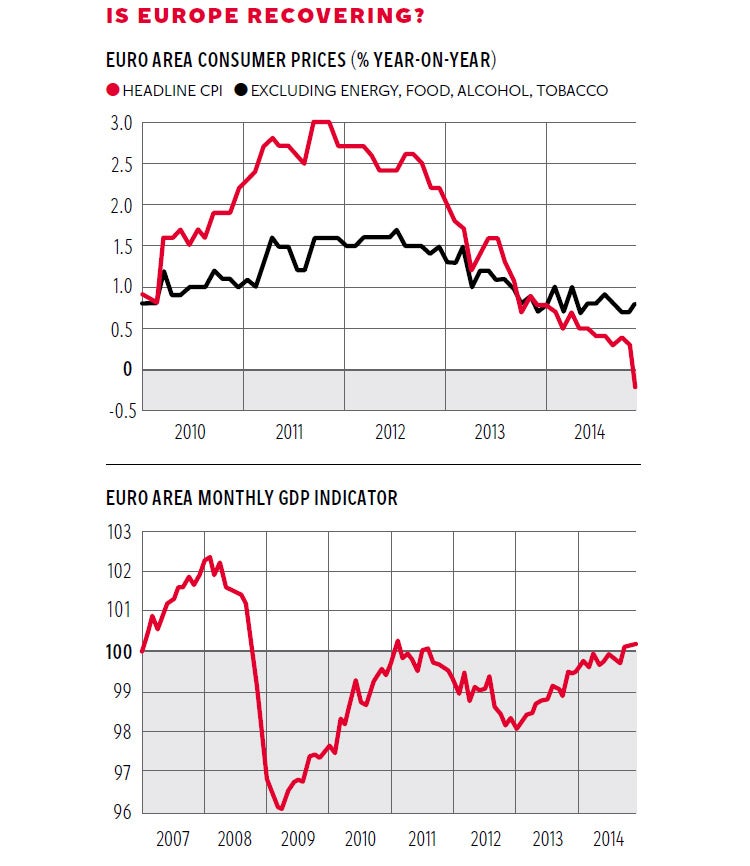

Two things have made such an outcome inevitable. The first was last week’s consumer price indices, showing that year-on-year eurozone prices were down 0.2 per cent. True, this was a function of the falling oil price and the underlying inflation was 0.8 per cent. But even that is far below the ECB mandate that inflation should under but close to 2 per cent, so on mandate grounds there is a clear case for action.

The second thing was the judgment by the European Court of Justice that the previous ECB plan for boosting the economy was broadly within its competence. If you don’t follow these things closely, all you need to know is that the plan, called Outright Monetary Transactions, is a sort of QE lite, and that the court’s initial opinion is thought more favourable to the ECB than expected. Now this is cleared, one road-block to a full-on version of QE is removed.

We will get an outline plan after the next ECB council meeting on 22 January. Given market sensitivities, there has been huge speculation as to what assets the ECB will seek to buy, whether there will be a ceiling on its purchases, and the mechanism by which it will do so. The detail affects market prices so that is understandable, but what matters to Europe as a whole is the likely economic impact.

The problem is sketched in the two graphs. On the top we have the slither of prices into negative territory, a slither that will continue for some months. The oil price is still falling, and while it cannot decline forever there is still a lot more deflation in the pipeline waiting to feed through. Underneath, there is what has been happening to eurozone GDP, and as you can see output is still shy of the previous peak. It has indeed been a lost decade for the eurozone.

So the question as to whether it will work falls into two parts. Will it get inflation close to 2 per cent? And will it support decent growth? I am more optimistic on the first than the second. Ignore the headline negative CPI and look at the underlying trend. Actually on the very latest data, core inflation is nudging upwards and given that the slump in the oil price will add somewhere between 0.25 and 0.5 percentage points to European growth you could quite easily see the headline number moving back to between 1 per cent and 2 per cent by the end of this year.

We know that QE elsewhere had added a bit to inflation, so a “close to but below 2 per cent” outcome is plausible a year from now.

As far as output is concerned, the calculation runs like this: there is already a tiny amount of growth showing through. Just yesterday there were good industrial production figures, and the new World Bank forecasts for the eurozone, while well down on earlier estimates, did expect 1.1 per cent growth this year. So the ECB would, so to speak, be pushing at an open door.

This is important. We know something about how QE works, but despite five years’ experience of it in the US and UK, we don’t really have that good a feel for what might happen in Europe. In both the US and UK we know that its impact on asset prices is very important. It did shave something off long bond yields in both countries, and in the US it seems to have a big impact on equity prices. In the UK it has been behind the recovery in house prices, though it has been less effective in boosting equities.

It is hard, however, to apply this knowledge to Europe. Bond yields in the eurozone are already in some instances below zero. Yup, below zero: the five-year German bund yield yesterday was minus 0.01 per cent. I happen to think this is madness. Indeed, the only way I can make sense of it is to see it as the markets expecting the eurozone to break up and bunds therefore to carry a capital gain when Germany leaves. Otherwise why on earth would you make a certain loss on your investment? But if you focus on the question as to whether QE will boost the economy, you have to acknowledge that it won’t happen through bond yields. If negative yields don’t help growth, why should even more negative ones do so?

Maybe action by the ECB might boost other asset prices without impacting bond yields. I can’t think through the mechanism except to note in the most general terms that if you spray money around it has to go somewhere. Maybe, too, it will depress the euro – the expectation is probably already doing so – and that will have a marginal positive impact on demand.

If all this sounds a bit negative, do however consider this. Maybe the best way to think about the potential impact of QE is to ask the question: might it make matters worse?

Surely it is very hard to see action by the ECB actually depressing prices or reducing output. If that is right, such action passes the test for all policy initiatives: first, do no harm. In the long run, as we know from American and British experience there are costs. Increased inequality is one; undermining the banking system as a mechanism for holding savings and supplying loans is another. In Europe the ECB might, by cutting the borrowing costs for fringe eurozone governments, undermine the impetus for reform – but that seems a bit unlikely. So, short-term at least, this will be helpful.

Have another look at the bottom graph. There is a modest upswing in place. If that carries on, eurozone GDP will, by the end of 2016, be back to the peak of 2007.

That conceals big national differences: Germany is already well past its previous peak, Italy will still be below its own one. But the lost decade is such a disaster that anything the ECB does should be welcomed – so let’s look forward to the announcement next week.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments