Hamish McRae: Deflation – like the falling cost of oil – isn’t a bad thing for most of us

Economic View: The euro has encouraged economic divergence, exactly the opposite to what its promoters predicted

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It has happened. The eurozone is in a state of deflation, in that consumer prices for the year to December fell by 0.3 per cent. The news has been greeted with concern, coupled with calls for the European Central Bank to take action at its next meeting on 22 January. But while this outcome is a long way away from the ECB target for inflation being below but close to 2 per cent, this form of deflation is a substantial net benefit to Europe, as indeed it is to nearly all the developed world. There are huge problems with the eurozone economy but deflation is not one.

If that statement seems a bit radical, consider this. Any fall in prices means people get more for their money: in other words it increases real income for any given money income. Since the present fall in inflation is driven almost entirely by lower oil and energy prices, this feeds straight into living standards. If you spend less money filling up the car you have more money to spend in the shops.

Apply this to the present inflation numbers for the eurozone. Prices overall are down by 0.2 per cent on the year. But if you take out energy, prices were actually up 0.6 per cent on the year. Take out food (the costs of which are largely energy-related), alcohol and tobacco, and inflation was up 0.8 per cent. Yes, underlying inflation is low and well below target, but energy prices will not fall forever and so the underlying or core inflation number matters much more.

Very low inflation does have the effect of maintaining the value of debt, in the sense that the real value of debts are not whittled away by inflation. Europe is heavily indebted, and you could argue that this will make it harder to pay off the debts. But there is the compensation that interest rates are historically low – negative in some instances – so the lower-than-expected servicing cost offsets the maintained real value of the principal. It is true that lower-than-expected inflation benefits holders of fixed-interest debt, whereas higher-than-expected inflation benefits the issuers of such debt. But this is part of the normal ebb and flow of advantage in financial markets. If countries struggle to service their national debt, they should not have borrowed so much in the first place.

This leads to two further issues. One is what very low inflation does to the economy; the other, what it says about the condition of Europe.

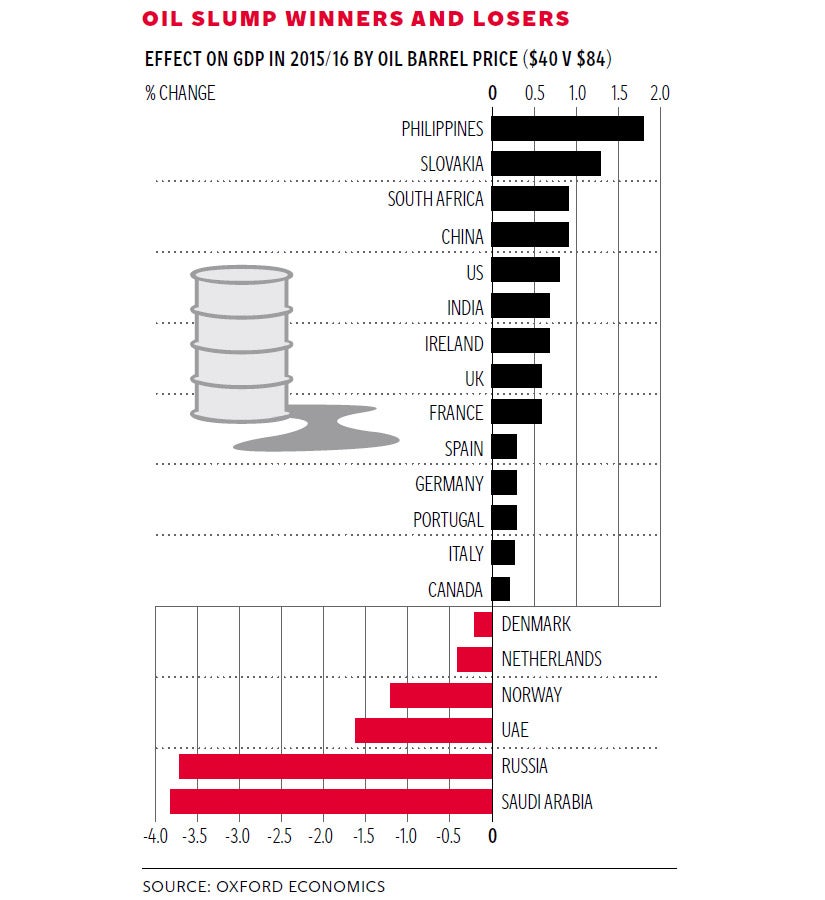

As far as the economy is concerned, there are winner and losers. Oxford Economics has done some calculations of the impact on growth on different countries on the assumption of an oil price falling to $40 a barrel. The graph shows what this might do to a selection of countries. Obviously, such a low price is very damaging to countries that rely overwhelmingly on oil. This is bad news for Saudi Arabia and Russia. But it is on balance very good news for most of the world, developed and emerging alike. There are even some big oil producers among the winners, including Canada and the US. China and India, both large importers, gain – China has become the largest oil importer in the world. In Europe, most countries gain. Three big eurozone countries, Germany, Italy and Spain all add around 0.25 per cent to GDP, while the UK and France are bigger net winners, adding about 0.5 per cent to GDP.

True, these calculations are based on an oil price that is probably unrealistically low. I can’t see oil being sustained at $40 a barrel for long. But the basic point stands: Europe benefits from cheap oil and we should therefore welcome this windfall.

Now to the second point: what does this very low inflation say about the eurozone more generally?

I suggest the best way to see this is to acknowledge that there are different reasons for the low inflation in different countries. To over-simplify, in Germany inflation is low because German companies have been very good at containing their costs. In France, Spain and particularly Italy inflation is low because of weak demand. You can see this divergence more obviously in unemployment rates, also published yesterday. German unemployment was down to 6.5 per cent, a record low, whereas Italian unemployment rose to 13.4 per cent, a record high. The euro has encouraged economic divergence, exactly the opposite to what its promoters predicted at launch.

However, we are where we are – or rather they are where they are. There is now, following those negative inflation numbers, overwhelming pressure on the ECB to announce some form of quantitative easing on 22 January. It is prohibited under its statutes from funding national governments, the method of QE used by other central banks; but it also has the inflation mandate noted above. Quite how it squares these contradictory obligations is a matter that will have to be sorted out. All experience of European negotiations is that this is about power, not about legality. Remember that when the powerful states, including Germany, exceeded the 3 per cent deficit limit of the Maastricht Treaty, they were allowed to do so with no sanction.

That is not to say that we get QE actually implemented this month. As a note from UBS points out, the ECB will be constrained by three things. One is the complexity of the project: this is much more complicated than the task of the Fed or the Bank of England, where the central bank simply buys the stock of the national government. The second is the fact that the Greek general election is on 25 January, so it might want to wait until afterwards to determine which national debt it should include in its buying programme. And the third concerns a European Court hearing on an earlier ECB programme, which complicates matters.

Still, while an announcement of intent might be enough to assuage the concerns of the markets, that is a long way from injecting significant demand into the eurozone economy. For that, we have to hope that the fall in oil prices does indeed do what those calculations in the table suggest it will.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments