Don’t panic! At least not yet – it’s time to take the long view on equities vs bonds

Economic View

At times like this – with the P-word (panic) starting to appear alongside the R-word (recession) – it is always best to go for the very long view. So the report by Credit Suisse Asset Management of long-term performance of different asset classes, just published, is especially welcome. This is one of two such annual studies, the other being the one done originally by stockbrokers de Zoete, the Z of BZW, and now produced under the Barclays wing. It isn’t out yet; however, the big messages from these exercises don’t change. On a very long view it is always better to hold equities rather than bonds, but there can be periods of several years when the reverse is true; that much of the equity return comes from reinvested dividends rather than capital appreciation; and that it is almost always wrong to hold cash.

Those messages come through in the new Credit Suisse report, which is done in conjunction with the London Business School, but there is something more: a comparison between the three great financial crises of the past 120 years, those of the 1890s, of the 1930s and the one from 2008 to the present.

What can we learn from the two previous crises? It is a subtle outlook, and a lot depends on policy response, but let’s start with the punchline. It comes from Jonathan Wilmot, managing director of Credit Suisse, and author of this part of the study: “Looking forward,” he writes, “we think zero real returns for developed market bonds and 4–6 per cent for equities would be a good working assumption. That means real returns on a typical mixed portfolio of bonds and stocks will likely be 1–3 per cent, down from around 10 per cent per annum over the past seven years. That is bad news for retiring baby-boomers and will pose a structural challenge for the fund management industry.”

Well indeed, and especially a challenge to the industry’s cost structure. You can get away with the typical 1 per cent annual management charge if you are getting 10 per cent returns, but not if you are getting only 1 to 3 per cent.

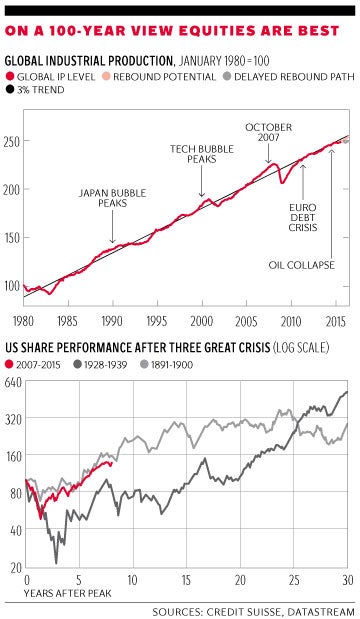

I will come back to how he reaches these conclusions in a moment. First, a look at the recovery. As you can see from the top graph, global industrial production has risen at a trend of 3 per cent for the past 35 years. There is a general perception now that somehow this trend has been broken, that there has been a permanent loss of output and wealth. I’m not sure this is true. As you can see, the four or five years before 2008 were exceptional, in that growth was clearly above the long-term trend, so some fall-back was to be expected. Since then we have recovered and close to trend and the question is whether we now fall back again or stick to it. For simplicity I have shown these two alternatives.

The main point here, surely, is that on the evidence so far the world economy is not in any sense broken, and if it continues to grow, companies operating in it will continue to do all right.

That does not, however, mean that the next decade will be easy for investors. Rather the reverse. First the outlook for bonds. Past experience suggests that financial conditions remain fragile for some years after a crisis, so bond yields remain low for seven to 10 years. After that the bear market in bonds begins. That would figure. We are seven years after the crisis now, and bond yields have remained exceptionally low. Those of us who expected the long bear market in bonds to have begun by now have been proved premature. But out there somewhere is a bear market, for the present ultra-low bond yields are unprecedented. Actually I think the turning point has been passed but who knows?

The outlook for equities is more positive, as the bottom graph shows. It shows what has happened to the real (ie inflation-adjusted) return on US shares during the 30 years after the three great crises. As you can see US shares are doing better this time than after the 1930s crash, but not as well as after the 1890s one. (UK shares, not shown, are doing worse than either. Mind you, the First World War did knock things back for us, though not for America.) Anyway, in all cases you eventually end up ahead; it just takes a while.

That is what happened in the US and UK. If you want the really long global view, the data looks at markets in 26 countries since 1900. In every single country, equities beat bonds and bills (a proxy for cash) over the 116-year period. The excess return averaged 4.2 per cent a year over bills and 3.2 per cent a year over bonds.

My own main takeaway from this research, aside from the point that it is almost always right to be invested in equities, is that we are likely to have several more years of sullen, tricky markets, with low or lowish real returns. The only question in my mind is to what extent past experience was skewed by two world wars. We have seen a huge expansion of debt but not nearly as huge relative to GDP as those two wars generated. We also have not seen the physical destruction, let alone the political and human upheaval. So, on the assumption that there isn’t another catastrophe of that order of magnitude on the horizon, could it be that the 30 years after the last crisis will be rather easier than the periods of 1890-1920 and 1930-60?

We see everything through the lens of the present. What is happening now, seen through the lens of, say 1910, is actually pretty normal. In fact, US real equity returns track that experience remarkably closely. That does not mean we should be Panglossian about the markets now, and I think that warning by Mr Wilmot to the fund management industry is most apt. But it is not, on past experience, time to panic.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks