A new global recession? There are reasons to be sceptical

Economic View

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The “Is this just a dip or is it something worse?” debate about the world economy has heated up a few notches. Forecasters have been historically poor at predicting recessions, despite the undeniable fact that there is a global economic cycle from which we seem unable to escape. But there are some market analysts who have become very bearish, and whether or not their fears are justified, those who have argued that as a result of these concerns any tightening of monetary policy worldwide is a long way off have so far been proved right.

One focal point for the debate has been the annual International Monetary Fund and World Bank meetings in Lima, Peru. The IMF’s new chief economist, Maurice Obstfeld, presented the new World Economic Outlook forecasts, which showed global growth slowing to 3.1 per cent this year from 3.4 per cent in 2014. This would be the slowest since the financial crisis, though the IMF does forecast growth to climb back to 3.6 per cent in 2016.

In questions afterwards, he was asked whether a global recession was looming.

“Global recession is certainly not our baseline scenario,” he replied.

So that’s all right then? Well, the danger of a hit from an emerging market credit crunch was highlighted by another paper from the IMF which warned that the withdrawal of stimulus measures in advanced economies could start a “vicious cycle of fire sales, redemptions, and more volatility” – as we report on page 51.

This is not a new fear by any means. Citigroup’s chief economist, Willem Buiter, warned last month that there was a 55 per cent chance of some form of global recession in the next couple of years, most likely one of moderate depth and length.

“The world appears to be at material and rising risk of entering a recession, led by emerging markets and in particular by China,” he said. “Economists seldom call recessions, downturn, recoveries or periods of boom, unless they are staring them in the face. We believe this may be one of those times.”

That is a bold view and one that deserves to be taken seriously, especially by those of us who incline towards the “mid-expansion pause” camp. A recession led by the emerging markets would be a first, for all recent global recessions have been led by the developed world, with the US going in first and Europe following on behind. The crude numbers just about work, because the emerging economies now account for some 35 per cent of global output, rather more than the US. This is quite different from the situation in the 1990s when the emerging economies last hit a serious downturn. Then they were closer to 15 per cent of the total, and their slowdown had little impact on the developed world.

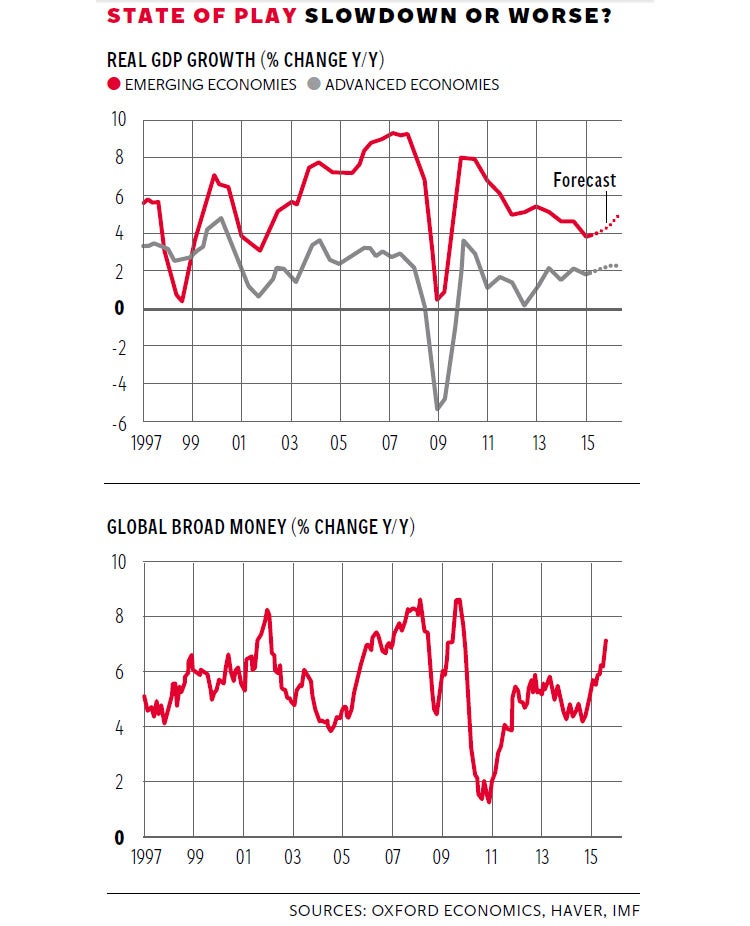

You can see this in the top graph, which comes from the IMF, updated to show this week’s forecasts. The Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s was the only time when emerging market growth dipped below that of the developed world. Since then growth has been consistently higher, and much higher in the early 2000s. Even now growth is projected to continue at roughly double that of the advanced economies.

But these are only forecasts. The obvious problem here, accepted by the optimists as well as the pessimists, is that were there to be another downturn, there would be hardly any room for policies to boost growth. Most developed economies are still running sizeable fiscal deficits and in any case it is not at all clear that loosening fiscal policy would increase growth. It might have the opposite effect because of its impact on confidence. As for monetary policy, more quantitative easing and more negative interest rates would at best give another upward kick to asset prices and at worst would be counterproductive because of a similar adverse impact. Look at the way the Fed’s decision to hold off an increase in rates last month damaged confidence rather than boosting it.

So if things do head south, nothing much can be done. But in assessing the risk, I think there are several positive points to be made. The first is that a slowdown in China, while damaging commodity exporters and China’s regional trading partners, would take pressure off energy and raw material markets. So other countries, and in particular those in the developed world, could expand without importing inflation from this source. Cheap oil, for example, would be here to stay. Real increases in our living standards would come as much from lower prices as from higher wages. We have very little recent experience of falling price booms, but they were a common feature of the 19th century.

The second point to be made is that there is still spare capacity in the developed world. You can have a debate about how much. You can argue that some capacity has been permanently lost following the last downturn, as people have moved out of the labour market (a loss of human capital), and factories and machinery produce goods no longer needed (a loss of physical capital). But looking around even relatively strong economies such as the US and UK, there is no sense of pressure in either the goods or service markets. There is pressure on infrastructure in both countries, and in some places on housing, but not in general productive capacity. In Europe and Japan there is a huge amount of spare capacity in both labour and product markets, no doubt about that.

Third, there are few general early warning signs of global recession in the money markets. In fact, global money supply growth is quite strong. The bottom graph, from a paper by Oxford Economics, shows how broad money supply has been surging this year. That does not of itself say anything about the future growth of global economic output, but it does show that there is no monetary constraint on growth. The IMF is right to warn about the impact of a credit crunch on the emerging economies, but there is no evidence of such a crunch yet. Moreover, what matters is supply of credit, not the modest increase in the cost of credit that is in the offing.

In short, we are right to be worried and the Buiter thesis may prove to be right. But even if it is, focus on the likelihood that the recession, were it to come, would be “one of moderate depth and length”. Indeed a moderate recession might be no bad thing; certainly better than the other sort.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments