A bumpy landing now for China would be better than years of stagnation

Economic View

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The best way to get one’s mind around the double devaluation of the Chinese yuan is to see it as part of a gradual progression from being a controlled currency, with the exchange rate set by the authorities in Beijing, to becoming a more normal one, with the rate set by the financial markets. We are still a long way from that, and China may never get there. There are advantages to pegging a currency rather than letting it freely float. But to see this as the start of a trade war, or a desperate measure to crank up growth, or a response to the impending rise in US interest rates, is to over-emphasise the short-term.

That said, the trigger is probably the prospect of higher US rates, because these are pushing up the dollar, particularly against the euro. The objective of the authorities is to maintain the yuan against a basket of currencies rather than pegging to the dollar as such – although that is how it is usually quoted. It follows that if the dollar rises, as it has been doing, the yuan is pulled up too far against the basket, so it has to devalue against the dollar to maintain the same overall level.

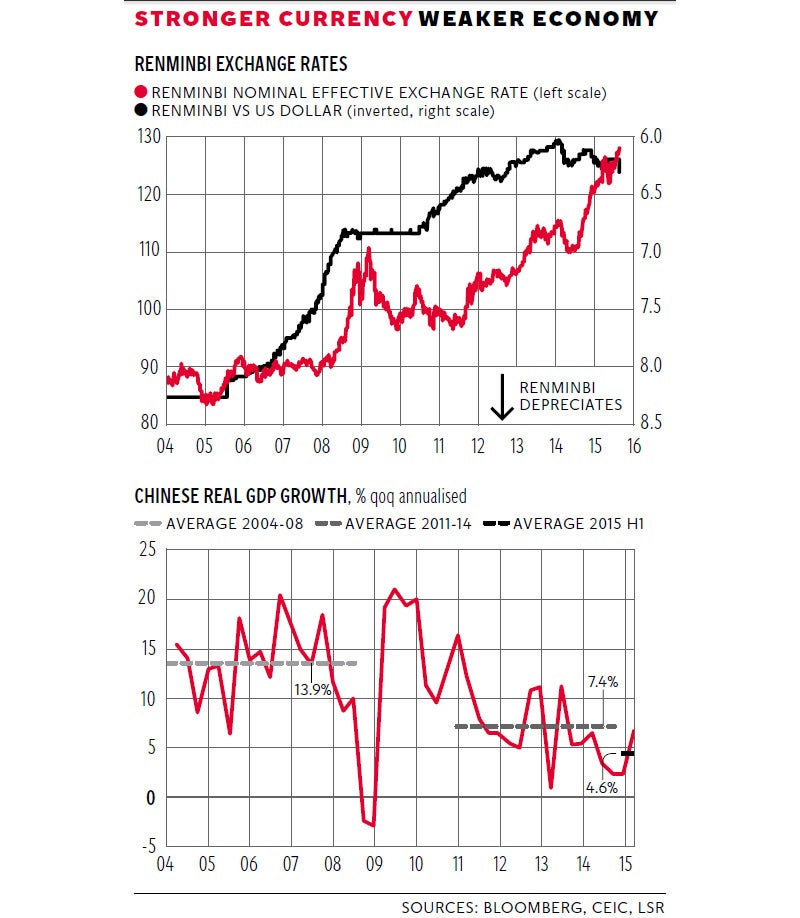

You can see this in the top graph. Over the years, far from weakening, the yuan has tended to strengthen against the dollar, as it indeed it has against other currencies. Its costs have risen, with wage rates in Shanghai now higher than in parts of the US. Other costs remain lower but the basic point is that its products are no longer cheap compared with those of other East Asian exporters, such as Indonesia. As Lombard Street Research noted in a commentary, whereas until 2008 it had an undervalued currency, it now has one that is overvalued by – depending on which measure you take – between 15 and 30 per cent. So you could see these devaluations, and I think there will be more, as trying to offset unwanted revaluation, rather than an aggressive attempt to gain market share by artificially depressing its currency.

Still, growth has slowed – and quite dramatically. You can see that in the bottom graph. That 4.6 per cent figure for the first half of this year is an estimate by Lombard Street Research; others have put it lower, with Fathom Consulting estimating current growth at just 3.1 per cent. Some sort of slowing was inevitable and welcome, but as we all know it is hard to transform a fast-growing economy into a moderately-growing one without triggering some sort of crash. In theory it should be possible, because everyone knows what must happen and accordingly should be able to adjust. In practice, people make mistakes. The most dramatic such failure was that of Japan. When its stock market and property bubble burst at the end of the 1980s, it avoided severe recession, but at the cost of two decades of stagnation.

The Japanese experience hangs over Chinese policy-makers. From a Western perspective the big current issue is whether China will avoid a so-called “hard landing” as it makes this transition to slower, but more sustainable, growth. That affects commodity and energy prices, and although they are relatively small still, it affects Western exports. Thus in the past days we heard that Jaguar Land Rover is being hit by lower vehicle exports to China. Actually a hard landing would not be all bad for the developed world as a whole, for it would remove pressure on commodities. (It would naturally be bad for developed countries that were commodity and energy exporters, such as Canada.)

The Chinese authorities are naturally concerned about a hard landing too. But I think their concern goes beyond that, for what they really are determined to avoid is two decades of stagnation. Whisper it low, but it may be better to have a sharp slowdown now and then kick-start growth thereafter, than to prop up the economy artificially right now.

If this argument is right, then the timing of this move has probably been determined by the desire to soften the transition to slower growth as well as offsetting the unwanted rise of the yuan in weighted average terms. But it will have been planned for many months and is consistent with the long term objective of making the yuan match the dollar as a reserve currency.

What does it mean for us? If this is just the modest exchange rate adjustment suggested here, not a lot. Any company that trades internationally is grown-up about exchange rate risk. What we are seeing is, as yet, an adjustment to counter the rise of the dollar. It will affect east Asian countries trading with China, and whenever you get a movement that is not expected there is always the possibility of it having unforeseen consequences. On the evidence so far I can’t see another east Asian financial crisis akin to that which happened in the 1990s, but it would be silly to rule it out.

If, however, China were to head into some sort of recession (and define at as you will), then the consequences would of course be massive, but unpredictably so. The great recession of 2008-09 was actually a recession only of the developed world. The emerging world, taken as a whole, continued to grow throughout, with the two biggest BRICs, China and India, losing only a couple of percentage points of growth. But that did not give much help to the developed world; indeed by maintaining high demand, and prices, for commodities and energy, it may have made it harder for developed countries to escape recession. They did not get the boost from lower commodity prices they might have expected to get at that stage of the cycle.

Now we are in the reverse position. Growth is picking up in most of the developed world but it is easing or has eased in three of the BRICs – India being the exception. The challenge for the West will be to engineer a smooth path back to sustainable rates of growth, with sustainable fiscal deficits and an end to ultra-low interest rates. The US will, as always, be the leader and will determine the outcome. The challenge for China is to become more normal too, growing at a sustainable rate, and loosening the remaining elements of a command economy. Allowing the currency to decline a little is a sensible bit of the programme. It may be China has a hard landing, but we should not yet assume that this is inevitable.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments