Hamish McRae: The Brics are banking on a rather old-fashioned idea to challenge US and Western dominance

Economic View: Is the new bank likely to be of much use? The emerging countries have done pretty well without it

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The Brics summit has produced, as expected, a rival world bank to be headquartered in Shanghai, with capital of $50bn (£29bn). It has also agreed to set up a currency reserve facility of $100bn that countries can draw on short term if they run into a balance of payments crisis. So the Brics are mirroring the twin institutions founded after the Bretton Woods Conference exactly 70 years ago, the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. What should we make of this?

It is, for a start, an astounding tribute to the power of an idea: the coining by Jim O’Neill at Goldman Sachs of an acronym to encompass the four largest emerging economies, Brazil, Russia, India and China. South Africa became the S, though it does not really qualify on GDP grounds and may not even be the largest African economy now, as it looks as though Nigeria has passed it.

If the big idea was a Western one, forming two institutions that copy the existing institutions (of which the Bric countries are naturally already members) is a further compliment to Western intellectual leadership. Indeed, both the World Bank and the IMF have become rather old-fashioned concepts. If an African country wants to obtain development funds it goes direct to China, rather than the World Bank – or at least it does if it has any natural resources. Or it goes to the private sector, importing access to markets and commercial know-how as well as the cash. As for the currency reserve, in a world of floating rates, you don’t really need an IMF. It was intended to help lubricate the fixed exchange rate system, which died in 1973. While it has subsequently had a role in bailing out countries that have made a mess of their finances – the UK in 1976 and much more recently the eurozone periphery – were it not to exist I don’t think the world would really notice. It shows a certain lack of imagination to create two new institutions when the present ones are becoming less and less relevant. Why do it?

Part of it is frustration with what is seen as a US-dominated system. Both the World Bank and the IMF are located in Washington and the US remains the largest shareholder. The head of the bank is, by tradition, an American; the head of the fund, a European. This anachronistic split holds true even when the appointee turns out to be incompetent, or misbehaves in other ways, as we recently found with Dominique Strauss-Kahn. (Dr Jim Yong Kim, current president of the World Bank, was born in South Korea, but moved to the US with his parents at the age of five.)

There is a precedent. When Europe wanted to direct more funds to Eastern Europe after the collapse of the Soviet Union, it formed the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. That echoed the full title of the World Bank – the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development. Recently the largest recipient of EBRD funds has been Russia, and there is pressure by the EU now to cut these funds, following the Ukraine emergency. From the Russian perspective the new bank is a bit of poke in the eye for the West.

For different reasons, it also suits China, which wants a greater global financial role, but is hesitant to let its currency be used for international trading. It suits India, which provides the first head of the new bank. It suits Brazil, where growth has slowed dramatically and which needs to rebuild its self-confidence. And it suits South Africa to have a place on the financial world stage.

If, however, you ask whether the world needs yet more international bodies, it is hard to sustain much of a case. Having a short-term lending facility that gives an alternative to the IMF has political attractions, and given the IMF’s poor performance with regard to the eurozone fringe (not to mention its absurd attack on the UK), having some sort of rival may be no bad thing. A competitor to the World Bank may also be marginally useful. Competition in finance for global infrastructure cannot be bad.

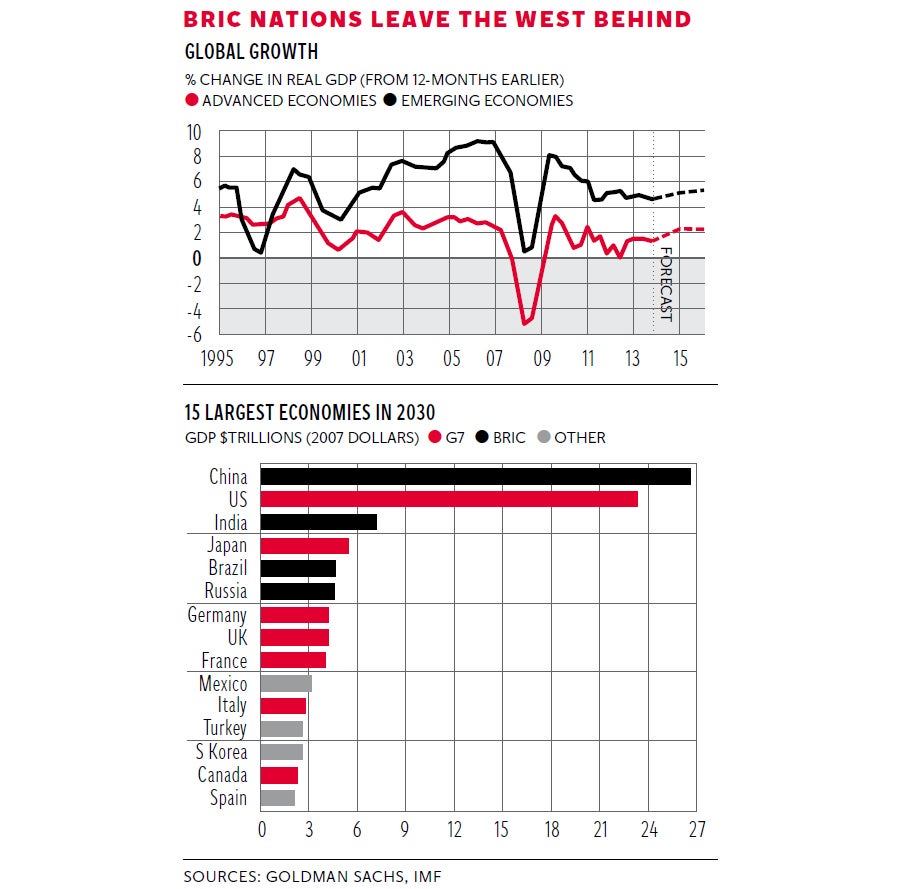

So the “first do no harm” stricture holds. But if you have a look at the two graphs you can see both why the emerging world hardly needs any new institutions, but also why it wants to have them.

The top graph comes from the IMF and shows how the emerging world (black line) has outpaced the developed world (red line) for the past 15 years. True, the gap is narrower now than it was in the early 2000s, but looking ahead the emerging world seems likely to grow at roughly double the rate of the developed world. Is a new bank really likely to be of much use? The emerging countries have done pretty well without it.

The second graph shows the pecking order in 2030, as projected by the Goldman Sachs model. As you can see, the four Bric countries (shown in black) occupy four of the six top places, while the G7 countries (shown in red) slip down the pack. South Africa does not register, demonstrating that its inclusion is political rather than economic. Stronger candidates as members of the club would be Mexico, which is part of Nafta; Turkey, which has a trade agreement with the EU; and South Korea, shown in grey. It is hard, however, to argue with the basic point that the world will, in 15 years’ time, be dominated by the Brics and that they must have a much more explicit role in the choreography of this economy.

That really should be the aim of the West: to get closer cooperation between all these new players, so that fostering world growth – and the handling of related issues such as environmental concerns – becomes the responsibility of all. We need the new economic powers to take on the role that their status demands. It may seem a pity that they should feel the need to set up rival bodies to the World Bank and IMF, though it is easy to see why. But since it is hard to see these bodies doing any harm, they surely deserve a welcome.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments