Hamish McRae: People are moving to where the jobs are – within Europe or outside

Europe is experiencing a huge shift in population, exacerbated by the eurozone’s rigidities

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.America seems to be detaching itself from Europe, so will the UK become more like the US or more like its EU partners? And what will Europeans do if growth outside Europe, and in particular outside the eurozone, fails to pick up as quickly as growth across the Atlantic?

One of the things that has become very clear in the past week is the pressure that Mario Draghi, president of the European Central Bank, feels he is under to deliver a better economic outcome for the eurozone.

The prospect of the US Federal Reserve preparing to tighten monetary policy pushed him into making it clear that Europe would not follow. Mark Carney, the new Governor of the Bank of England, said much the same, though less explicitly. But he is under less pressure, for the UK could stand somewhat higher long-term interest rates in a way that the eurozone cannot. Mind you, Dr Draghi has more leeway in policy because eurozone inflation remains appreciably lower than British.

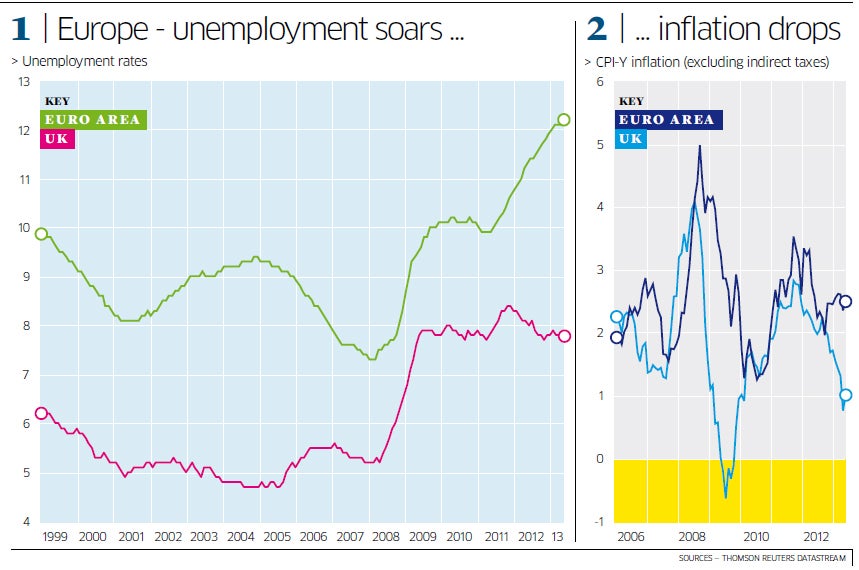

Europe's somewhat better inflation performance (right-hand graph) but much worse unemployment outcomes (left-hand one) have become glaringly obvious.

The eurozone numbers span a diverse economic region, so in a way the aggregates are misleading, but the plain truth is that the ECB is responsible for monetary policy of that entire region and it has to have a single set of interest rates.

The dilemma has become even more clear in the past few days, for unemployment rates are now becoming, if not a targeted variable, at least an indicator that central banks are taking much more seriously.

In the US there is a specific level of unemployment, 6.5 per cent, that the Fed would like the economy to achieve before it starts increasing interest rates. Here there is not as yet any such precise level, though we may get guidance on this in the next few months, but a similar 6.5 per cent target is being mentioned. (The US is currently at 7.6 per cent; we are at 7.8 per cent.) We have no idea what the equivalent rate for the eurozone might be, but the level being spoken of is something around 10 per cent.

That raises a host of issues. One is that it highlights the dispersion of unemployment rates.

As a note from Jefferies, the investment bank, points out, unemployment in the eurozone ranges from Austria at 4.8 per cent to Spain at 26.3 per cent, whereas in England it ranges from 6.2 per cent in the South-west to 10.1 per cent in the North-east. (On the narrower claimant count calculation unemployment in the South-east is the lowest, down to 2.7 per cent.)

Another is to ask why at the height of the last boom eurozone unemployment only dipped briefly below 8 per cent and was more than 9 per cent in 2004-05, a period of decent growth. This is a policy failure, however you dress it up.

But the question that is surely most important is this: what will people do? By that I don't mean what policy-makers will do, but rather what will ordinary people do?

The answer, for many of the young at least, is that they move. Europe is experiencing a huge shift of population, driven by economics and exacerbated by the rigidities of the eurozone. People are moving to where the jobs are, both within Europe and outside it.

We catch a glimpse of that in Britain, particularly in London, which is projected to add another 2 million to its population over the next 20 or so years. But what we are getting is a worm's eye view of a much wider phenomenon.

Within Europe, the two countries according to the OECD that are experiencing the greatest inward migration are the two outside the EU, Switzerland and Norway.

If on the other hand you are viewing from Portugal, you see young people going to jobs in Brazil. If you are viewing from Romania, you will have seen the population fall by 2.6 million over the past decade, with that decline quite possibly speeding up in recent months. And if you are viewing from the US, you see the magnet for talent as strong as ever. If you stand back, there are, I think, two broad trends. One is that Europe is developing a single labour market.

One of the main economic criticisms of the EU has been that, unlike the US, it had a fragmented labour market. Goods could move about freely; services moved about to some extent; but labour did not move.

The fact that the region has such diverse levels of unemployment would support that. But now those levels have become so diverse that people are starting to move where the jobs are. Some are moving to Germany, which has a shrinking domestic labour force. Others are moving to the UK.

The second broad trend is to move out of Europe altogether. If as now seems to be happening the US grows quite a lot faster than the eurozone and continues to do so for the next five years, then that trend will pick up pace. It will become self-sustaining because population growth brings economic growth, which in turn attracts more job-seekers.

The first of these two trends was really one of the objectives of the EU, for free movement of people means free movement to where the jobs are. The second trend absolutely was not.

That is something that will become a rising concern. At the moment the focus of policy is on unemployment, and in particular youth unemployment. (In Britain we may be doing relatively well in overall job creation, but we are not doing at all well for the unemployed young.)

I expect policy concerns in much of the eurozone, though not the UK, to shift to something even more fundamental: why do our young people have to move abroad to get a job?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments