David Blanchflower: Young people are suffering from austerity in the UK as well as in Greece

By one measure youth under-employment is worse in the UK than it is in Greece

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Enough is enough. At some point the Greek people were bound to say they were done with austerity, and last week they stood up and said we need some hope. It was time to get out of their Great Depression. What else could they do? Austerity, according to the European Commission/European Central Bank/International Monetary Fund “Troika”, was supposed to lead to the sunlit uplands. Always a pipe dream.

Overly tight fiscal and monetary policy was inevitably going to crush the Greek economy, and so it did. Austerity resulted in a drop in GDP since the start of the crisis of 28.8 per cent. Greece has a health crisis, with HIV rates up 700 per cent. Malaria has returned for the first time in 40 years, and there is widespread malnutrition. The Greek healthcare system is collapsing as a result of spending cuts, and children are not being vaccinated. Reductions in pay have resulted in thousands of doctors leaving for the UK, Germany and Scandinavia.

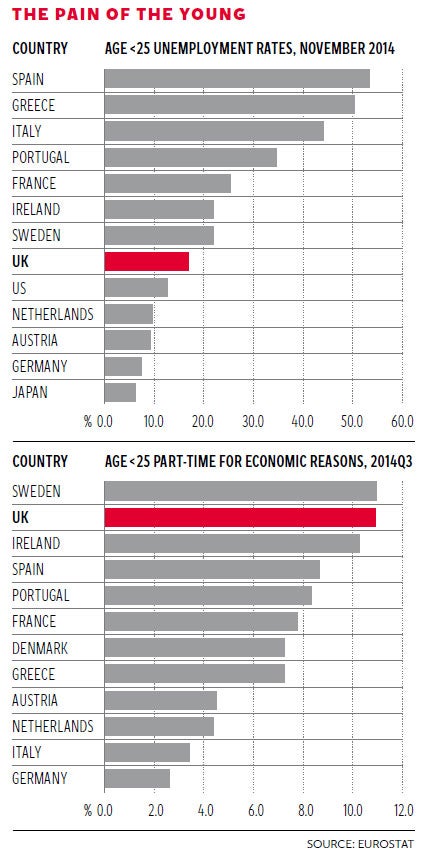

Unemployment in Greece has been above 25 per cent since July 2012 and shows little sign of declining. It currently stands at 25.8 per cent. The first chart shows that the Greek youth unemployment rate is over 50 per cent. It was 21 per cent at the beginning of 2008, but has been above 50 per cent since November 2011, and shows little sign of declining. The youth unemployment rate in Spain is also over 50 per cent, with overall unemployment at 23.8 per cent. In comparison, the most recent estimate of youth unemployment rates in the UK is 16.7 per cent, on the rise again though, up from 15.9 per cent in June 2014.

The second chart is also worrying. It suggests that youth under-employment is worse in the UK than it is in Greece. It plots under-employment rates for young people across Europe. Here under-employment is measured by the proportion of the youth labour force (unemployed plus employed) that are in part-time jobs for economic reasons. That is, they are involuntarily part-time, preferring full-time jobs. Around 11 per cent of the youth labour force in the UK and Sweden are under-employed by this measure, which is the highest proportion in any of the 28 EU countries, including Greece (7.3 per cent) and Spain (8.7 per cent).

Among 25 to 74-year-olds the UK ranks sixth, behind, in order, Cyprus, Spain, Ireland, France and Greece. Youth under-employment rates in the UK are joint highest in the European Union.

The young have been the biggest losers of austerity in the UK. They have been hit by a double whammy. They can’t get jobs but when they do they are often temporary, low-paid and with fewer hours than they would like. The general election is likely to be determined by whether these young people turn out to vote.

According to new estimates from the Bell/Blanchflower under-employment index for Q3 2014, published by the Work Foundation today, there is an additional 1.5 per cent of under-employment over and above the unemployment rate. Our index measures the total number of additional hours workers would like to work, including both full-timers and part-timers. This series isn’t available for other countries. In the case of young people under the age of 30, the gap is 7.5 per cent, so that means the under-employment rate is around 24 per cent.

In the case of young blacks, the gap between the unemployment rate and the under-employment rate is 14.2, taking them to a Greece-like under-employment rate of 44.5 per cent. So our estimate is that rather than the official unemployment rate of 5.8 per cent, the “real” rate, taking into account under-employment, is 7.3 per cent. This is a large amount of slack, and helps to explain why there is no evidence of any pick-up in wages.

The other news last week was a drop in GDP growth in the UK to 0.5 per cent, which is consistent with the evidence from surveys and other business and consumer sentiment indices that the UK economy is already slowing. Of interest is that the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee had forecast that GDP growth would be 0.75 per cent for the third quarter, plus that data for the prior 18 months would be revised upwards. Another embarrassing miss.

The likelihood is that the strengthening of the pound against the euro will have major downward effects on activity in the UK. Since May 2014 the pound is up 12.5 per cent, from €1.19 to €1.34, against the euro.

This is likely to hit especially hard in Northern Ireland, with its open border with the Irish Republic. My concern is that shoppers in Belfast now find it beneficial to take the train to Dublin, where goods are now markedly cheaper.

It was rather surprising, then, to find that the external MPC member Kristin Forbes in a speech in London focused on the possibility that the risks to the MPC’s forecasts for the UK could well be to the upside, and growth would be even stronger than forecast. The main reasons she gives are: 1) Stronger global GDP growth; 2) Smaller labour supply; 3) Faster productivity growth. To me, all of these risks are dominantly to the downside. Global GDP growth is already slowing. There is no sign that migration or potential migration from Eastern Europe has slowed, and the amount of labour market slack remains high.

In its forecasts the MPC has already assumed that the productivity puzzle is fixed, although it is unclear why. To argue that the risk to the forecast is that productivity takes off even faster stretches credibility too far. Forbes argues that “these scenarios, if they occur, would imply an earlier increase in interest rates than currently expected”. They sure would. Pigs might fly too.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments