David Blanchflower: Why do the Tories have such a big problem with trade unions?

An outbreak of industrial relations warfare is not good for productivity or worker management relations, or share prices for that matter

The Tories are vindictively planning to accelerate trade union demise by introducing new rules regarding minimum turnout in ballots for a strike. What strikes? They are now at historic lows. Where exactly is the big problem here anyway, given how little bargaining power trade unions have with so much slack in the economy? Wage growth isn’t taking off. Productivity shows no signs of improving, either. Last time around it was the disabled; this time, it’s union members.

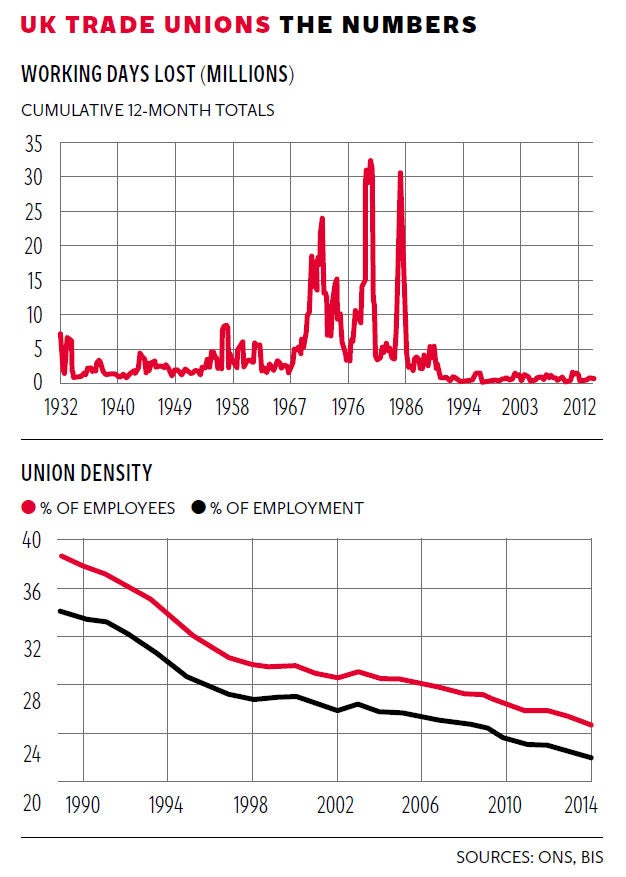

The first chart makes clear that there haven’t been many strikes for years. The graph plots the number of working days lost in the form of cumulative 12-month totals in thousands. So a strike of one day of 1,000 workers counts the same as a 10-day strike of 100 workers. Over the last 12 months through March 2015 they averaged 716,000, which contrasts with an average since 1931 of 3.9 million cumulative days lost.

Central bankers can’t seem to get out of their minds the burst of inflation observed in the 1970s and 1980s, while right-wing politicians seem fixated on the strikes that occurred at the same time. The numbers of days lost have had three peaks. The first was January 1975, of 15 million, with the really big one in April 1980 (32 million), and with a third peak in February 1985 (30 million). Since November 1990 there hasn’t been a single month above 2 million lost days. Even that number of days is high, of course, but needs to put in context that with a workforce of just over 30 million that amounts to 7.7 billion working days.

We should also note, though, that while a strike may simply be about flexing muscles, it may also indicate a failure of management as much as a failure of workers. It takes skills to negotiate a settlement. Workers may have more power than managers think, and vice versa. Disrupting public services is a big deal because of the harm it causes, but might in the end just show to the public how much power these workers have. Strikes are power struggles and sometimes are simply about asymmetric information and often occur as a result of a mistake.

One of the major contributing factors to fewer union workers going on strike is that there are just fewer of them. According to data from the Department of Business Innovation and Skills, membership reached a high of 13.2 million in 1979 but it has been downhill since then. In 2014 there were 6.75 million union members.

Of course there has also been a rise in population and employment over these years, so the proportion of workers in unions has fallen sharply, as the second chart shows. Union density is higher among employees than it is among all workers, so the rise in self-employment has also contributed to the fall. Among employees, density is down from 39 per cent in 1989 to 25 per cent in 2014, and 34 per cent and 22 per cent respectively for all workers.

Union coverage, though, is higher: 43 per cent of employees are in workplaces where pay is covered by collective bargaining arrangements.

Private-sector union density is much lower than public-sector density (14.2 per cent and 54.3 per cent). Today the majority of union members in the public sector are women, although they remain in the minority in the private sector (65 per cent and 44 per cent respectively). Density is much lower in England (24 per cent) than it is in Wales (36 per cent), Northern Ireland (35 per cent), or Scotland (30 per cent), and lowest in the South-east and London (19 per cent), so any attempt to weaken unions is going to exacerbate further the regional divide. Union membership rates are especially low among the young, which does not augur well for the future of trade unions.

This has striking similarities to what has happened in the United States, where the union density rate has fallen sharply over the years. It is now 11.1 per cent overall, and 35.7 per cent in the public sector and 6.6 per cent in the private.

In 2013/14 union membership rates were highest in New York (24.6 per cent) and lowest in North Carolina (1.9 per cent). Union membership rates among young American workers are also especially low.

Of interest, though, in both countries is that union workers are paid a significant wage premium. In the UK the average hourly pay of union workers is £14.77, compared with £12.66 for non-union workers, giving a differential of 16.7 per cent. In the US in 2014, among full-time wage and salary workers, union members had median usual weekly earnings of $970, while those who were not union members had median weekly earnings of $763 – a 27 per cent differential.

It looks like it’s only the strong unions that remain. In both countries a significant union wage differential remains even after variations in personal and workplace characteristics are accounted for. Over time these differentials are shrinking.

In their famous 1984 book What Do Unions Do? Freeman and Medoff argued that unions had two faces: their monopoly face, where they can raise wages, and a second, more desirable side, their “voice” face. This enables unions to channel worker discontent into improved workplace conditions and productivity. If unions are to survive, they are going to have to emphasise that voice face.

Recent research from the National Institute of Economic and Social Research has mixed news for unions. They continue to reduce worker quit rates, just as Freeman and Medoff found, laying the foundations for increased employer investment in training and high-performance work systems. But employers are also benefiting from non-union forms of voice, such as town hall meetings and problem-solving groups, which offer employers the prospect of hearing workers’ voices without mediation through a union.

One thing I learnt many years ago in my studies of trade unions is that you can’t legislate good industrial relations. Poking the workers in the eye with a sharp stick is unlikely to provide a boost to morale, productivity or job satisfaction; in fact, probably the opposite. Disgruntled workers don’t show up on time and absenteeism rates rise. It is all too easy to throw a spanner in the works. An outbreak of industrial relations warfare is not good for productivity or worker/management relations, or share prices for that matter. These are what are called repeat games as negotiations happen every year. When times improve, workers will remember. If I lose on the roundabouts, I get my own back on the swings.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments