David Blanchflower: There is no doubt that leaving the European Union would hurt Britain

A 'Brexit' would raise the price of your goods and services

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The Tories and Ukip want a divisive European Union referendum which the economic evidence suggests would result in an economically damaging British exit (Brexit). Being inside a free trade area with an external tariff barrier provides major advantages; leave it and you are subject to that barrier, which raises the price of your goods and services.

At my golf club in the mountains of New Hampshire, if you want to play, you have to pay. If not, buzz off. The EU has essentially the same rules, and the European Commission made clear this week that they are not about to bend them to suit Cameron. And not to mention the almost inevitable prospect of losing the UK’s seat at the Security Council.

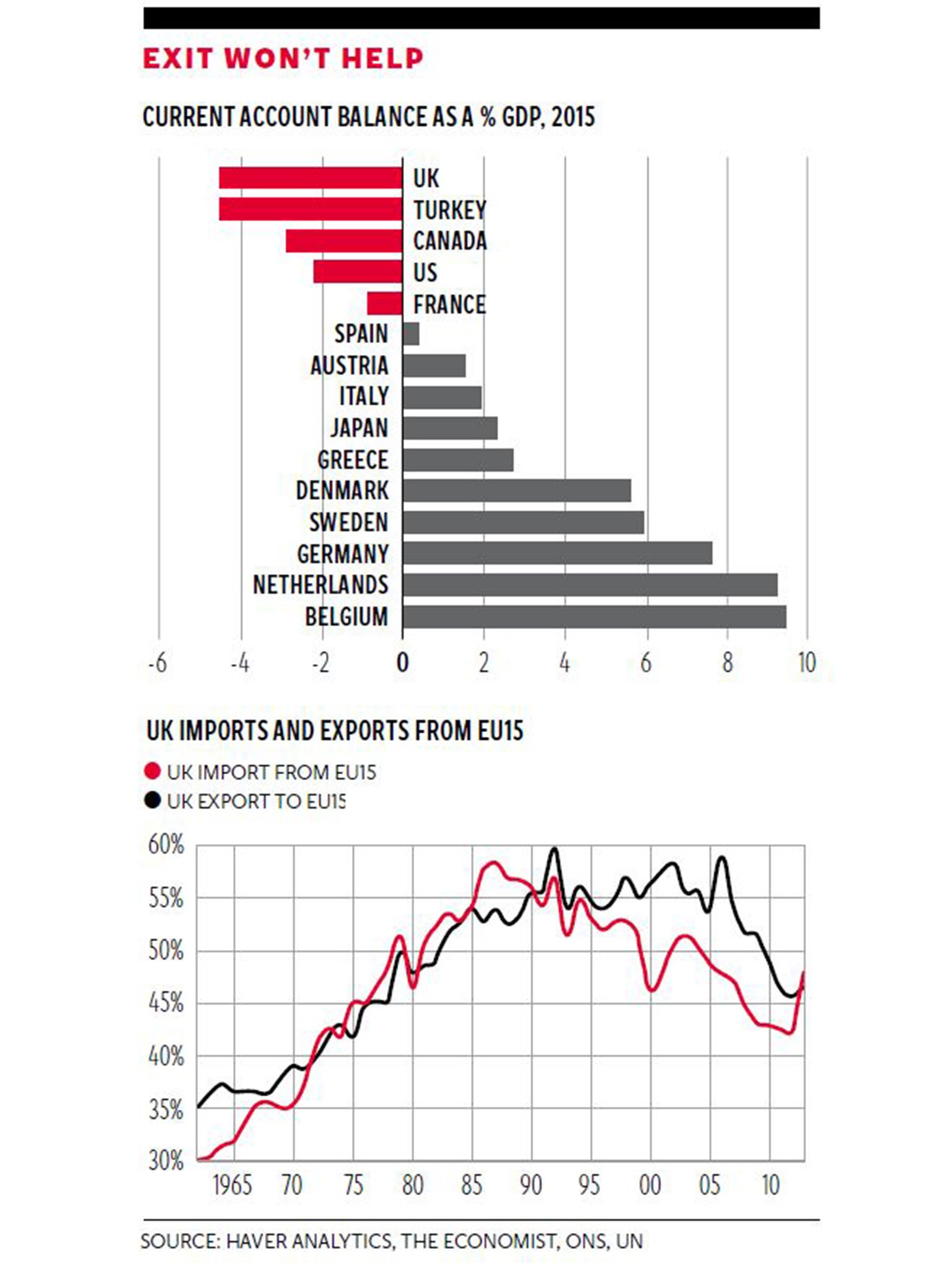

Brexit does seem a particularly bad idea given that the UK is experiencing a major problem with its current account balance, which is now in record deficit. There has been no march of the makers and we aren’t exporting enough. The first chart plots the current account balance as a per cent of GDP for 15 major countries. The UK, with 4.5 per cent, ranks joint last with Turkey. We need to protect the shrinking export markets we still have.

Major UK businesses are opposed to Brexit; the CBI has announced it is against. A recent study by the accountants Deloitte revealed that chief financial officers (CFOs) suggested that even a referendum itself would cause harm. The second biggest source of anxiety after the general election outcome was the potential turmoil of a vote on Britain’s membership of the EU. CFOs reported on the level of risk where zero is none and one hundred is the highest possible risk. They awarded 56 points in Q1 2015 to Brexit compared with 50 points in Q3 2014, so risks are rising. Rising perceptions of uncertainty have already dampened corporate risk appetite and fed through to a softening of investment intentions. An EU referendum, let alone exit, would inevitably create harmful market volatility.

Opposition to Brexit also seems to be rising fast among the British public: the majority are now against. In 73 surveys since 2010 the survey firm YouGov has asked respondents “If there was a referendum on Britain’s membership of the European Union, how would you vote?” Possible responses were remain in the EU or leave the EU, with the remainder saying I won’t vote or I don’t know. Between 2010 and 2013 the average responses were 34 per cent for and 45 per cent against, with the remainder non-responses. In 2014 the averages were 40 per cent and 39 per cent respectively. The latest three surveys in 2015 average 45 per cent for staying in and 36 per cent for leaving.

A recent study from the Centre for Economic Performance* has measured the impact on the UK economy of leaving the EU, which as the second chart shows is still the UK’s biggest trading partner. When the UK joined the EU in 1973, just over 30 per cent of UK exports went to the EU. By 2008, over 50 per cent of UK exports went to EU countries. The authors argue that Brexit would lead to lower trade between the UK and the EU because of higher tariff and non-tariff barriers to trade. In addition, the UK would benefit less from future market integration within the EU. The main benefit of leaving the EU, of course, would be a lower net contribution to the EU budget.

The authors of the study consider an “optimistic scenario” with small increases in trade costs between the UK and the EU, and a “pessimistic scenario” with larger increases. In the optimistic case, Brexit reduces UK income by 1.1 per cent of GDP. In the pessimistic case, UK income falls by 3.1 per cent (£50bn per year). In the long run, reduced trade may also lead to slower productivity growth. Factoring in these effects, they argue, “could easily more than double the costs of Brexit and lead to a loss in the pessimistic case comparable to the decline in UK GDP during the global financial crisis of 2008-09”. To have a sense of how many jobs could be lost, from peak to trough in the Great Recession, unemployment in the UK increased by nearly 1.2 million.

Leaving the EU, the authors suggest, would also affect foreign direct investment (FDI), immigration and economic regulation in the UK. These effects are harder to quantify than changes in trade, but are likely to lead to further substantial declines in income. The UK received the most FDI of any European country in 2011, and of all the countries in the world, only the United States has a higher stock of inward FDI. Part of the attraction of the UK for foreign companies is as an export platform to the rest of the EU, so if the UK is no longer the gateway, this position is likely to be threatened. On exit the UK could restrict immigration from the rest of the EU, while UK citizens would be likely to face reciprocal restrictions on their ability to live and work in EU countries. Restricting this mobility will, just like restricting trade, reduce overall UK welfare. Prices of goods will rise. A counter-argument is that immigration from the EU has harmed UK-born workers in terms of jobs, wages and access to public services. But there is no compelling evidence of any significant negative economic effects of immigration in the UK. So the job losses could easily be two million or more.

As a member of the EU, the UK is able to influence the rules and regulations governing the EU single market. Even if the UK maintained full access to the single market following Brexit, it would be in the same situation as Switzerland and Norway: UK exports would have to obey EU regulations, but the UK would not have a seat at the table when the rules of the single market were decided. The study concludes that reduced integration with EU countries is likely to cost the UK economy far more than is gained from lower contributions to the EU budget. Hence “staying in the EU may cause political trouble for the major parties; but if the UK leaves the EU, the economic trouble will be double”. An economic tsunami. I am against.

* S Dhingra, G Ottaviano and T Sampson (2015), “Should we stay or should we go? The economic consequences of leaving the EU,” Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments