David Blanchflower: Reasons to be concerned by the rise of self-employment

Self-employment conveys considerable risks: many lose their jobs, their houses, and even their marriages

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Since the Coalition took office in May 2010 the number of self-employed is up, in the most recent data for August 2014, by around 570,000. That’s a 14.2 per cent increase, compared to a rise of 4.3 per cent in the number of employees.

There are currently 4.5 million self-employed, of whom around a quarter report being part-time. The self-employment rate (SER), which is just self-employment divided by total employment, is currently 14.7 per cent. For men the SER rose from 17.9 per cent to 19 per cent (+324,000) while for women it went from 7.2 per cent to 7.9 per cent (+246,000) since 2010.

Self-employment conveys considerable risks, not least when there are large amounts of labour market slack. Of people who were self-employed in 2009, 23 per cent were no longer so in 2014. There is some evidence that when the self-employed fail, as many do, they lose their jobs, their houses that they used to finance their work, and sometimes even their marriages. Around half of employees say they want to be self-employed; fortunately, most don’t take the leap.

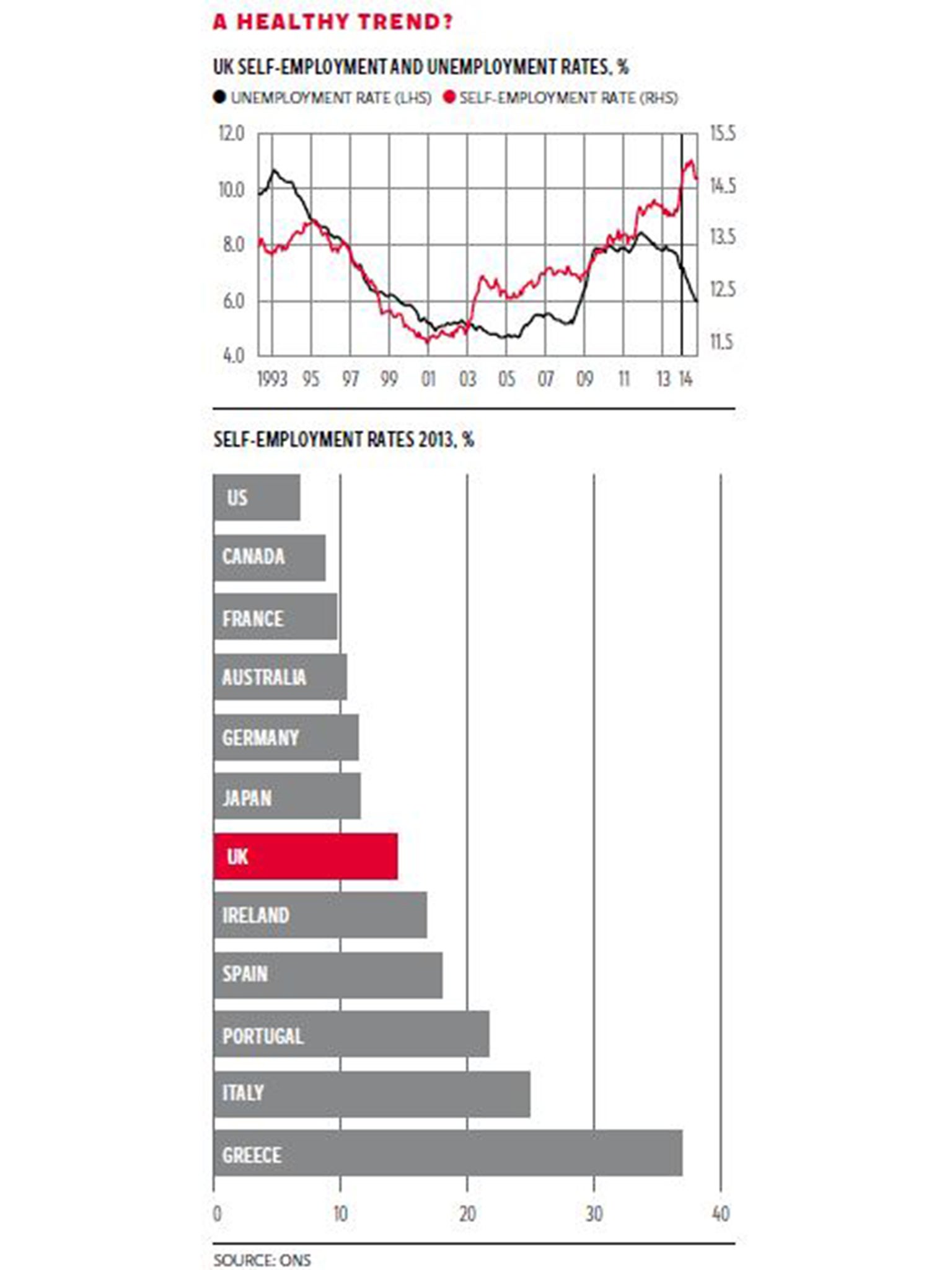

The first chart shows a rise in the SER in the early 1990s, then a drop through 2001, and then a steady upward path since then, with an especially steep path in 2013, with some recent slowing. It appears that the peak number of self-employed may have been passed. There were 4,608,000 in May 2014 compared to 4,520,000 in August. The chart also plots the unemployment rate on the right-hand axis, and it is clear the two series are strongly positively correlated.

As the unemployment rate fell in the 1990s the self-employment rate also fell. During the recession it rose. In the most recent period as unemployment started to fall so did the self-employment rate. As unemployment rises, self-employment rises potentially as an alternative to unemployment. This is push. Benefit claimants are pushed into low-paying self-employment.

There is, though, another kind of self-employment. In good times, when unemployment rates are low, employees realise there are opportunities out there to strike out on their own. They have been pulled rather than pushed. The new self-employed are disproportionately likely to say they are underemployed, desiring more hours. They are hours-constrained. Recently, push seems to have dominated pull.

The question is whether that implies there has been a burst of entrepreneurial spirit or not. I suspect not. Interestingly, a declining SER is generally better as it is an indicator of development. Poor countries have high self-employment rates, especially in agriculture, and as the country becomes less rural, and more advanced, SER declines. Mexico has an SER of one third, Chile’s is a quarter. The second chart shows for 2013 the countries with the highest self-employment rate in order are, Greece (37 per cent), Italy (25 per cent), Portugal (22 per cent), Spain (17 per cent) and Ireland followed by the UK (14 per cent).

Self-employment is predominantly, but not exclusively, a male phenomenon, being especially important in construction, which has seen a big decline in its numbers as the sector has still not recovered to pre-recession levels. The SER rises with age, and the number of over-65s who are self-employed has more than doubled in the past five years. The SER is higher among whites than other groups, with the exception of Pakistanis, who have especially high rates. Blacks have relatively low rates. Self-employment tends to be higher if the individual comes from a family where others are self-employed.

Workers in education and the health sector are frequently self-employed as a second job. Sometimes it is hard to work out which is the prime job, as some workers, including some academics, earn more from their self-employed (second) jobs than in their employee (first) jobs.

In work I have done with Andrew Oswald* we find little evidence that you can predict who is going to be self-employed based on childhood characteristics. It is hard to predict who will be a pop star or another Richard Branson at age 11. They don’t appear to be more risk-prone when they are young. It is important to do this by looking at childhood characteristics before entry to the labour market so we can distinguish what is learnt from what is inherited. We do find that capital constraints bind, which means the credit crunch has likely had a major impact on the returns to self-employment and survival rates. Lending to small and medium-size enterprises continues to fall, making it especially hard for the self-employed to prosper.

We do know from HMRC records that the mean earnings of the self-employed are higher than those of employees, because the average is pulled up by the very high earners. But the typical self-employed worker, at the middle of the earnings distribution, is paid less than the typical employee, noting of course that the self-employed can have negative earnings or losses. So there are a few very highly paid football players with huge salaries that pull up the mean but the typical player at the median earns much less.

Evidence from the Family Resources Survey suggests that the self-employed saw a very large real fall in their median earnings in 2012/2013 of 12 per cent and down a whopping 22 per cent since 2008/9.

The self-employed are excluded from all three of the main earnings measures published by the ONS. This needs to change so we can closely monitor how they are doing. My best guess is: badly.

A rise in the numbers of self-employed by half a million doesn’t mean the UK has become more entrepreneurial. As I found in a 2004 research paper**, more self-employment does not seem to be better.

* David G. Blanchflower and Andrew Oswald, 'What makes an entrepreneur?', Journal of Labor Economics, 1998

** David G. Blanchflower 'Self-employment more may not be better', Swedish Economic Policy Review, 2004

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments