David Blanchflower: Prices are easing and industry is slowing. Why on earth would we put up interest rates?

The underlying trend in factory output is its weakest since the start of 2003

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The big economic news this week is that prices continue to tumble. Brent crude oil futures are now trading at $96.98 a barrel, down from $115 in mid-June, which will push down on inflation. Commodity prices are also falling sharply.

The broad Bloomberg Commodity Index is now at 122, down from 136 in mid June. CPI inflation is below target at 1.6 per cent, which is the second highest rate of any European country; only Austria at 1.7 per cent is higher. Inflation in the eurozone recently dropped to 0.3 per cent.

Three EU countries have inflation rates of zero –Estonia, Italy and the Netherlands while seven European countries have outright deflation: Bulgaria (-1.1 per cent), Greece (-0.8 per cent), Portugal (-0.7 per cent), Spain (-0.4 per cent), Slovakia (-0.2 per cent) plus Switzerland (-0.1 per cent). The latest to be added to the list of countries with outright deflation is Sweden, where the CPI inflation fell 0.2 per cent in August.

Deputy Governor Lars Svensson resigned earlier this year because the Swedish central bank, the Riksbank, had raised rates. His argument was: “When unemployment is so high, it wouldn’t be a problem if inflation overshot the target a bit.

Rather than test deflation, it would be better for the economy to push inflation beyond its 2 percent target to 2.5 per cent, or something like that, to lower unemployment.” The unemployment rate in Sweden is currently 7.9 per cent with private sector wage growth in June 2014 of around 2.5 per cent.

There is an election in Sweden on 14 September. The failure to deliver on its inflation mandate has made it a focus of the election campaign, with the Social Democrat-led opposition that is ahead in the polls, demanding the Riksbank pursues policies that support employment.

Real wages in the UK continue to tumble, indeed in the latest data releases nominal and real wage growth are both falling.

Comparing the most recent three month period with the previous three months, (April-June compared to January to March 2014), according to the Labour Force Survey weekly earnings of full time workers in Scotland is down 2.4 per cent, compared to a growth of 8.6 per cent per cent in London. No wonder the independence vote is too close to call.

Despite all of this acute disinflationary and even deflationary pressure, two external members of the Monetary Policy Committee, Martin Weale and Iain McCafferty, voted for rate rises in August.

Maybe they will learn from the Swedish example and change their ways at the next meeting. Recently Professor Simon Wren-Lewis on his must-read Mainly Macro blog posed an interesting symmetry test for the two I call the Irrelevant Minority (IM), given that the MPC is tasked with a symmetric target, of preventing inflation getting too far above or below the 2 per cent target. Imagine, he suggested, the economy is just coming out of a sustained boom.

Interest rates, as a result, are high. Growth has slowed down, but the output gap is still positive. Unemployment is rising, but is still low (say 4 per cent) and below estimates of the natural rate. Wage inflation is high as a result, and real wages had been increasing quite rapidly for a number of years. Consumer price inflation is above target, and the forecast for inflation in two years’ time is that it will still be above target.

In these circumstances, would you expect some MPC members to argue that now is the time to start reducing interest rates? Wren-Lewis suggests it is unlikely they would ignore the fact that price inflation is above target, wage inflation is high, the output gap is positive and unemployment is below the natural rate, and discount the forecast that inflation will still be above target in two years time. There is always a chance, Wren-Lewis says, that they might be right to do so, but can you imagine it happening? Hung, drawn and quartered.

There was other not such good news on the UK economy that suggests that the economy may well be slowing. First there was data from the housing market, which appears to have reached a plateau. The number of sales agreed last month fell for first time in nearly two years according to the Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors. Estate agents also reported a slowing of growth in house prices last month, particularly in London.

There was also weak data on industrial production. UK factory output rose year on year in July, but the underlying rate of growth appears to have eased from the strong pace of expansion seen earlier in the year. Factory production remains 7.2 per cent smaller than prior to the financial crisis. Production is consequently 0.1 per cent lower in the latest three months compared to the prior three month period, while manufacturing is down 0.6 per cent.

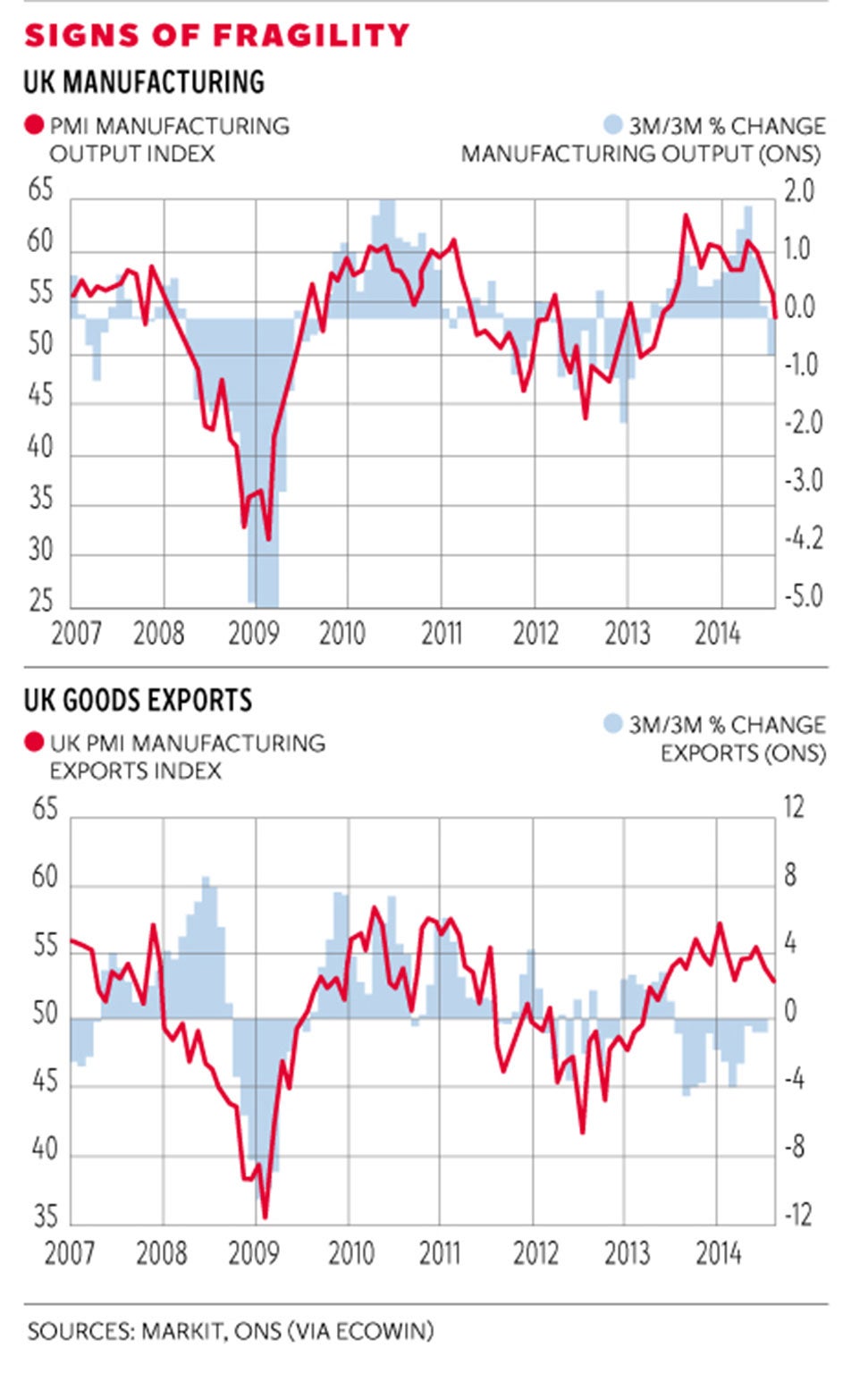

The underlying trend in factory output is the weakest since the start of 2013. Chris Williamson of Markit, who kindly provided the two charts, points out that the weaker official production data correspond with a similar picture from the business surveys, which suggest that factories have struggled over the summer compared to the strong growth enjoyed earlier in the year. The Markit/CIPS manufacturing PMI plotted as the dark line in the chart signalled a marked easing in the rate of growth of factory activity in August.

The trade data from the ONS last week was also poor. The UK’s deficit in trade in goods and services rose from £2.5bn in June to £3.3bn in July. The deficit in goods widened by £0.8bn to £10.2bn, its highest since April 2012 and one of the largest on record. The second chart plots the change in exports, which shows again slowing in both the official and survey data.

The survey data confirmed export growth slowing to the weakest since April, contributing to the smallest monthly expansion of activity in the sector for just over a year. No rebalancing.

Williamson argues that “although the three PMI surveys collectively indicated that the economy is still on course to have grown by 0.8 per cent again in third quarter, buoyed by faster growth in services and construction, the slowdown in manufacturing raises concerns that the wider economy may also weaken in coming months.” Especially if there is a premature rate rise.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments