Why has the Turkish lira slumped to a record low?

What’s driving it down? And what does it mean for Turkey and others?

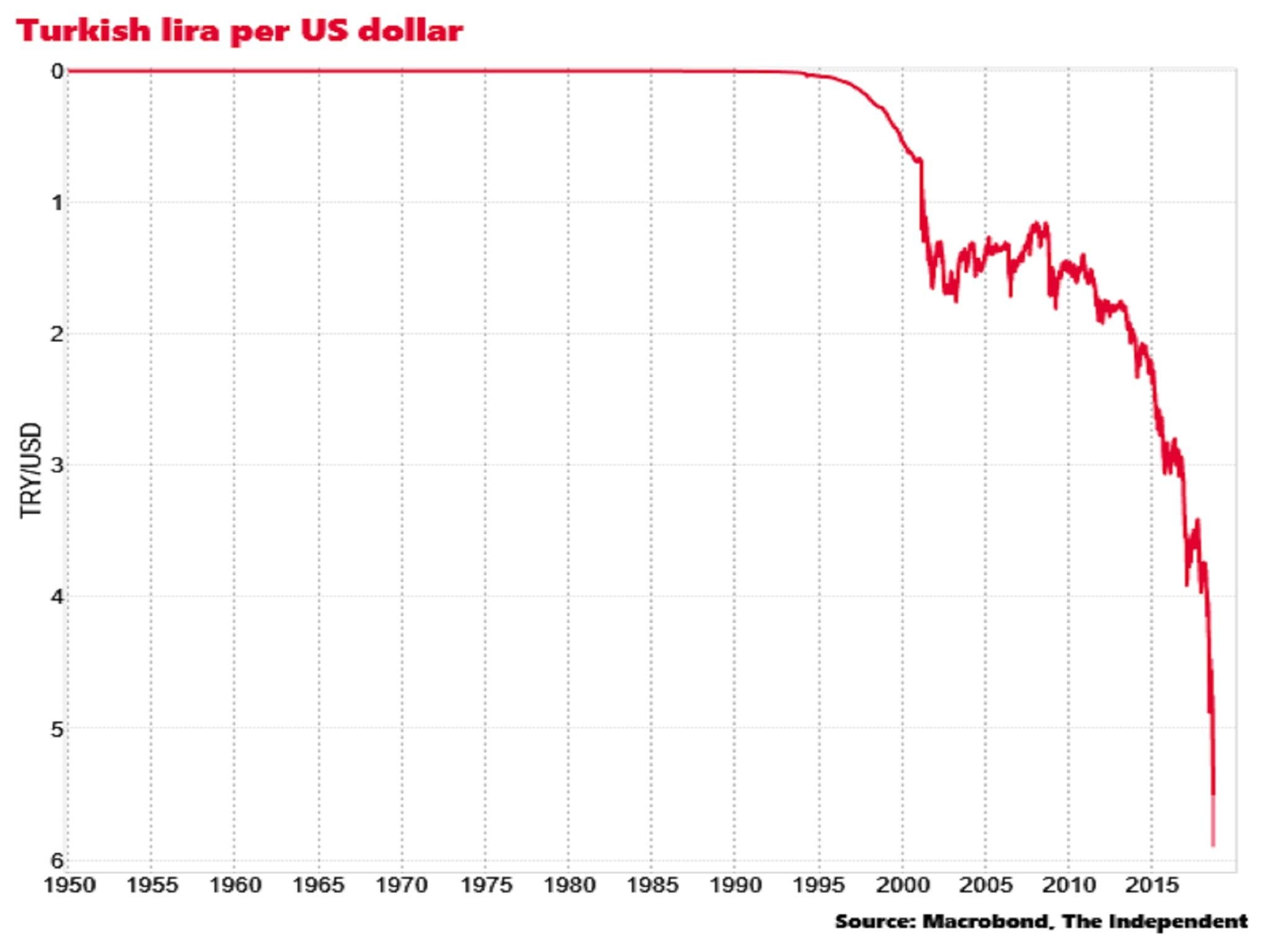

The Turkish lira has slumped to a record low against the US dollar this week.

On Friday it was down by as much as 17 per cent before recovering slightly.

What’s driving it down? And what does it mean for Turkey and others?

How much is the lira worth now?

At one stage on Friday afternoon one dollar bought 6.9 lira.

In January a dollar bought just 3.7 units of the Turkish currency. That means it has lost around 44 per cent of its value against the dollar this year.

The lira is now the world’s worst performing currency in 2018, overtaking crisis-hit Argentina.

And things have got worse very rapidly this month. The currency has experienced 12 straight days of decline.

Is there any financial contagion?

The currency rout has hit the country’s bond market. The yield on 10-year Turkish debt has jumped close to 20 per cent, making it much more expensive for the Ankara government to borrow.

There is also concern about the exposure of European banks such as BNP Paribas, UniCredit and BBVA to borrowers in Turkey. Their share prices were down around 3 per cent on Friday.

If Turkish borrowers are not hedged against the collapsing lira the fear is that they could default on their foreign currency loans, forcing European banks to make expensive loan write-offs.

For the same reason Turkish banks could also be in trouble given the amount of foreign currency lending they have undertaken.

Data from the Bank of International Settlements points to dollar claims of $148bn (£116bn) and euro claims of €96bn (£86bn) among local Turkish lenders.

What’s the cause of the crisis?

It’s a combination of factors.

The proximate cause is a diplomatic row with the US over the detention in Turkey of US pastor Andrew Brunson. Brunson was arrested in October 2016 accused of aiding an organisation which the Turkish government says was behind a failed coup attempt that year.

Last month Donald Trump called Brunson’s detention “a total disgrace” and the Washington administration announced last week that Turkey’s duty-free access to the US market is being reviewed, which could hit $1.66bn of annual Turkish imports.

On Friday Trump also tweeted that he was doubling steel tariffs on Turkish steel imports, writing: “Our relations with Turkey are not good at this time!”

But there are underlying causes too. Investors’ confidence in the economic competence of the Turkish authorities has been eroding for some time.

The country has a large current account gap, equivalent to 7 per cent of GDP last year. That means the economy is heavily reliant on foreign money inflows.

Inflation has also soared to 15 per cent, three times the central bank’s 5 per cent target.

Such figures are not particularly unusual for an emerging market economy like Turkey, but President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s slide into capricious authoritarianism has made investors doubt whether he can handle the crisis in a rational way.

“If they have their dollars, we have our people, our God,” he proclaimed this week.

Erdogan argues, bizarrely, that lower interest rates reduce inflation, rather than stoke it, and and has repeatedly sought to pressure the nominally independent central bank against lifting borrowing rates.

Turkey’s finance minister, Berat Albayrak, announced a “new economic model” for the country on Friday afternoon, claiming: “At the heart of the systematic problems experienced by a large number of countries lies the absence of sustainability. The new system will be sustainable. It will be participatory.”

But the fact that Albayrak is Erdogan’s son-in-law underlines the extent to which nepotism has now corrupted the administration in Ankara, casting doubt on whether he or his father-in-law have the credibility to stem the market panic.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks