What does the university loans accounting change mean for students and the government?

What’s the reason for the reform? And what will it mean for students and government ministers?

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) announced a major change in its treatment of student loans in the national accounts on Monday.

But what’s the reason for the reform?

And what will it mean for students and government ministers?

How are student loans currently accounted for?

Essentially they are treated as a repayable loan from the government to students.

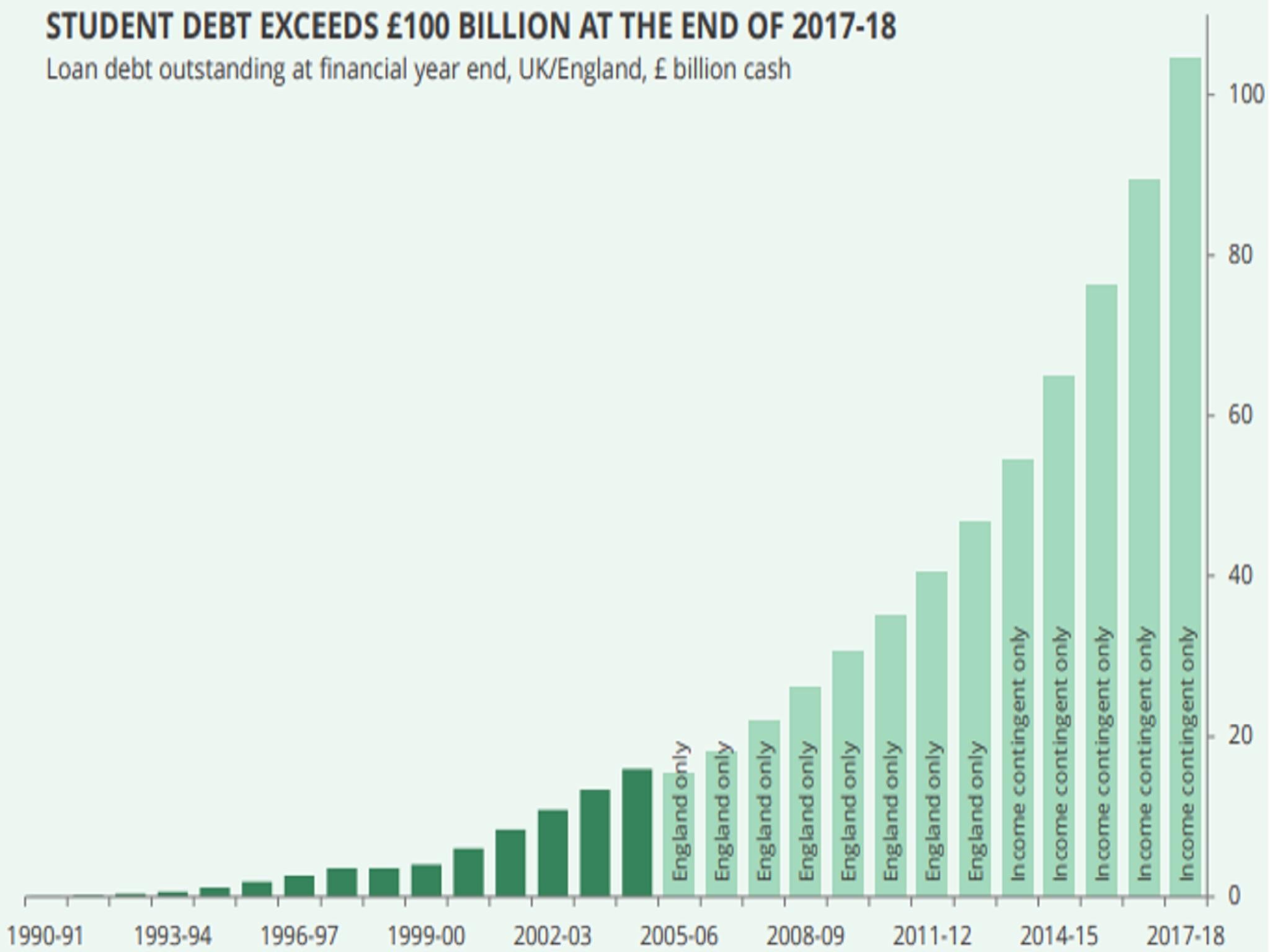

For various technical reasons, this means that when the government borrows money (around £16bn a year) from the financial markets and hands it over to students so they can pay universities for their tuition the sum is added to the national debt (the stock of government borrowing).

But it does not affect the deficit (the annual extra borrowing judged to have been done by the government).

It would only show up in the deficit if and when the loan is not repaid.

What’s the problem with this?

The design of the student loan system is such that a large proportion of the value of those loans (almost a half) is not expected to be paid back when they are made.

For instance, if a student does not earn above a certain income threshold (currently £25,000) in their future working life they never commence repayments.

And after 30 years (following graduation) any student’s outstanding debt is written off.

This write-off element makes a large tranche of these loans more like a government grant than a loan.

In theory this doesn’t matter. The government deficit will simply swell when the loans are written off three decades after they are made.

But, in practice, that’s when today’s cohort of politicians will be long retired, meaning the system arguably creates a temptation for them to create an abundance of loans today knowing that the fiscal consequences of the repayment shortfall will be some future politician’s problem.

Meanwhile, the accrued interest on the stock of loans is currently counted as government revenue, despite the fact that much of it will never be paid, meaning it flatters the picture of the deficit today.

Another complication is that (again for financial accounting reasons) if the government sells off the packages of student loans to private investors, as it has been doing, the transaction artificially flatters the national debt.

This arguably creates a temptation for ministers to sell the loans to the private sector for less than they are truly worth.

Such distortions, it is widely agreed, make the current accounting system unsatisfactory.

The government’s official spending watchdog, the Office for Budget Responsibility, says that the accounting treatment of student loans creates “fiscal illusions”.

So what has the ONS ruled today?

That the portion of new student loans that are expected to be written off when they are made by the government will be included in the annual borrowing figures.

This is estimated to increase the annual deficit by around £12bn, of 0.6 per cent of GDP.

The official accounts are set to reflect this change from the Autumn of 2019.

The national debt will be unaffected.

What does it mean for students?

Nothing changes directly.

The size of their personal nominal debt remains the same.

And so do their repayment and write-off conditions.

However, some fear that the accounting change, by pushing up recorded government borrowing today, could influence ministers to reduce the amounts available in student loans, or prompt them to tighten up the repayment terms.

What does this mean for the Government’s finances?

The £12bn increase in the deficit is bad news for the Chancellor, Philip Hammond, because he has made a reduction in the deficit a central part of his fiscal mandate.

He has committed to cutting the deficit to below 2 per cent of GDP in 2020-21.

He is currently projected to achieve that with around £15bn to spare.

This accounting change threatens to wipe out almost all of that leeway.

This may put him under pressure to either miss his target or to raise taxes or cut spending (all politically difficult) if the economy stumbles and tax revenues undershoot expectations.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks