Start of a new era for UK trade? Britain's new city-sized superport built to handle ships longer than the Empire State's height

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Last autumn, one ship passed another in the Thames estuary, a brief meeting of bookends to a whole history of British trade and seafaring. One was the HMS London, a warship which lay at the bottom of the river mouth after it was sunk in 1665 in a freak explosion.

The London was discovered during surveys for the construction of Britain's first new port in a generation, which was about to receive its first vessel: the MOL Caledon, nearly eight times the length and, fully laden, 60 times the weight of the ancient ship it passed.

When the London sank with its 300 men, Britain was beginning the period of colonial exploration and exploitation which would make its capital the centre of global trade and the world's largest port. That status would be ended in the 1970s by vessels like the Caledon: giant container ships which demanded deeper ports than the Thames could offer. These giant ships slashed the costs of transport, and reshaped the global economy.

At the same time, container ports took docks away from the heart of major cities, and hid them behind secure fences, border controls and radiation detectors. As global trade surged, with 90 per cent of it coming by sea, shipping somehow disappeared from public view.

But driven by the need to cut the costs of bringing goods to the consumer, the opening of the new port has brought shipping back close to the UK's most populated areas – on a scale which the Thames has never seen before.

"The Victorians knew what they were doing. The Romans knew what they were doing," says Xavier Woodward, communications manager for the new port, called London Gateway. "Of course you bring your ships into London and the south-east if you have the ability to. But for the past 50 years, we haven't had the ability to, because the Thames hasn't been deep enough."

The Caledon was led down a newly-deepened shipping channel which had been designed to skirt the wrecked ship, out of respect for history but also out of fear: debris from past wrecks could shred the hull of container ships, which can extend up to 16 metres into the water, skimming just a metre above the riverbed along the path dredged clear for them.

The ship had begun its journey in South Africa. Shipping lines, which each year transport and track nearly 500 million container shipments, criss-cross the globe in circular routes with regular stops, like bus routes operating on a grand scale, with journeys covering thousands of miles and lasting weeks.

After stops in Durban and Port Elizabeth, the Caledon picked up a cargo of wine and fruit in Cape Town, which would have been recognisable at any point in London's millennia-long history of international trade.

Its 17-day journey would take it along the west coast of Africa, past Algeciras in the Strait of Gibraltar, another stop on the South Africa to Europe line, before rounding the Iberian peninsula, heading down the English Channel and into the estuary.

There it was guided by pilot boats past the 17th-century wreck and other ships sunk in the Second World War, to dock at London Gateway, which lies about 10 miles outside the M25. Despite the distance, the site has a pedigree of London trade: the construction unearthed ancient Roman saltworks, whose products would have been sold upriver in the city, along with wine and olive oil from Europe.

By contrast, the 18,000 bottles of wine in the first container lifted from the Caledon would be transported on dedicated 'wine trains' to a warehouse in Daventry, for distribution by a large supermarket chain.

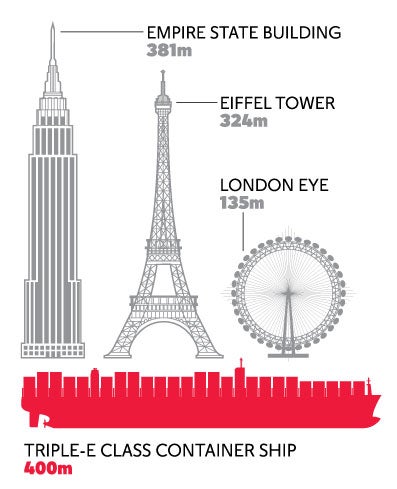

But the ship would bring more in its wake: it was followed earlier this year by the largest vessel ever to enter the Thames, the Gudrun Maersk. At over 115,000 tonnes fully loaded, it was almost twice the capacity of the Caledon. And in April, the port will open the second of six proposed berths, in a bid to capture the high-volume trade from Asia which increasingly is being carried by ocean-going juggernauts.

These triple-E class ships stretch for a quarter of a mile and carry over 18,000 standard 20-foot containers, enough to hold a billion dollars of cargo; if you tried to unload them in one go, the line of trucks would stretch for 68 miles.

This is the global race: the effort to move ever increasing volumes of trade ever more cheaply, by relentlessly increasing the scale of transport and moving it with computer-controlled precision.

London Gateway's owners expect it to handle 3.5 million containers a year when complete. Its owner, the Dubai government, predicts that the volume of trade through its 60 ports will rise from about 50 million containers last year to 92 million by 2020, driven by demand from developing countries.

And just as the Docklands was shaped by the sugar industry and slavery in the West Indies, London Gateway is built for our modern economy. As a brand new port close to an expensive city, it bucks the global trend, because it is a port built for consumption: importing goods, mainly from Asia, and sending back mostly empty containers, Scotch whisky, and waste paper, ready to be recycled in China back into more packaging for the next round of consumer products.

"It's like a Formula 1 pit stop," says Woodward, as he shows us around the port. A triple-E class ship would be likely to unload around 2,000 containers and load a similar number in a 24-hour period: that means a box weighing up to 30 tonnes moved every 21 seconds, non-stop. Time is money: even with small crews, often from Asia on wages of around $1,000 (£615) a month, the ships cost $75,000 (£46,000) a day to run.

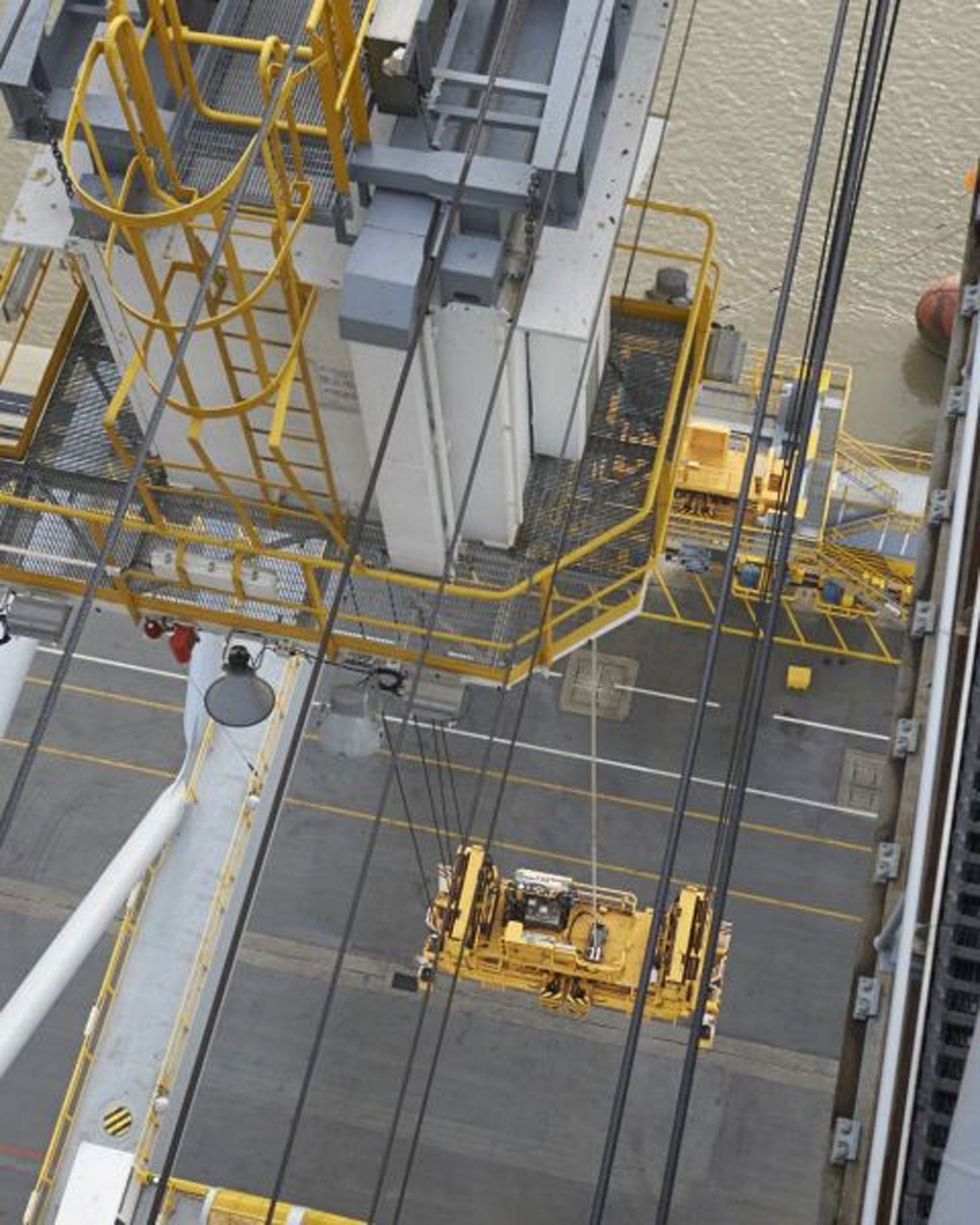

The people responsible for loading and unloading are suspended in tiny cabins with glass floors near the top of the 138 metre cranes – about as high as the London Eye. "They all want to work on the quay cranes," says the shipside superintendent Trevor Crickmar, as he leads us upwards, "90 per cent of them anyway – except the ones afraid of heights."

Quay crane drivers have to guide the 'spreader' which locks around the sides of containers to lift them: they are aiming for holes measuring four inches by two inches. Drivers only work for about three hours at a time to maintain their concentration.

Crickmar has 23 years working in docks and has seen everything pass through ports in the south of England: the Back to the Future DeLorean, unexpected migrant stowaways. He worked his way from the lowliest job of locking the containers in by hand, all the way up to the cranes.

"You are fighting the wind, the fog, the snow," Crickmar says. Did he get good at fairground grabber games? "Everyone asks that. I'm absolutely brilliant; you should see how many teddy bears I won at Clacton Pier."

Opening the Thames to such huge ships meant reshaping the estuary itself. The harbour walls where the cranes sit descend 14 storeys into the ground – about the height of the Lloyds building – to withstand the shock of a collision with one of the gigantic ships.

The land the cranes stand on didn't exist a few years ago; it was reclaimed by dredging millions of tonnes of silt to deepen the bottom of the river, which was then used to build out the banks by 500 metres.

Other land was taken from its occupants, who had to be rehomed: 350,000 wild animals which had taken over the site, formerly an oil refinery, after it lay derelict for 10 years. Farmers were paid to provide homes for great crested newts; others, such as bats, badgers, water voles and snakes were captured unhurt and transported at night in what Natural England says was Europe's biggest operation to relocate wild animals.

Downstream, however, another historic industry is suffering. The Essex town that holidaying Londoners ruefully nicknamed Southend-on-Mud is drying up: it's the opposite of what many feared from London Gateway's dredging, which was expected to cause silt to build up on the shore. But now locals wonder if the work hasn't made the tides stronger, stripping away the mud that is home to cockles as well as worms for bait and birds.

"It's barren," says Peter Wexham, a retired fisherman and councillor for nearby Leigh-on-Sea, where the cockle industry is centred. "The cockle boats could only work for 40 days last year."

Other fishermen say their catches have dried up since dredging began: one boat which used to bring in eight tonnes of smelt, last season only hauled in a quarter of a tonne.

A report by the Environment Agency could not detect any changes to the mudflats beyond their usual year-to-year ebb and flow, though it admitted that the data, some of which was supplied by DP World, needed to be more detailed.

Back at the port, not only the wild animals seem missing; the quayside is eerily still. Even allowing that only one of six berths has opened, there are few people about. The machinery runs quietly and the predominant noise is the warning beeps of the moving cranes.

When Joseph Conrad wrote about London docks at the beginning of the last century in The Mirror of the Sea, he described the wharves as crowded with a "swarm of renegades".

"The labour of the imperial waterway goes on from generation to generation, goes on day and night," he wrote. "Nothing ever arrests its sleepless industry but the coming of a heavy fog, which clothes the teeming stream in a mantle of impenetrable stillness."

Now, even London fog cannot stop the port. On our visit, the estuary disappears into the mist; port staff pass around a photo of the day before, when only the tops of the tall cranes could be seen above thick fog.

What keeps the port going is the same thing that keeps it unpopulated and quiet: automation. Although the port expects to hire 12,000 workers when it is fully operational, most of them will be in the nine million square feet of warehouses that will make up the logistics park – a space which could accommodate The O2 eight times over with room to spare.

Only the quay cranes need human operators – even these at some ports can be operated remotely, like a video game. When they release containers, they are picked up by purpose-built trucks which straddle the containers; these carriers can operate without drivers, guided by magnets embedded in the ground.

They place the containers in stacks, which are piled up by automated cranes according to a complex matrix of rules: whether they contain hazardous material, whether they are full or empty, when they need to be loaded on a ship, and so on. It is these which were able to follow their programming even in zero-visibility and keep the port working.

"The shipping line gives us a manifest, telling us where every container is on the ship and what's in it. We put it into the machine, the computer maps out where stuff can go," says Woodward. "What we're working to is this: it will handle 3.5 million containers per annum, so working out the best possible place to put stuff, it's like a giant version of Tetris – the most complex version of Tetris you can have."

No system is perfect, especially with half a billion container movements tracked by shipping lines worldwide. According to The Box, a history of containerisation by Marc Levinson, the contents of millions of containers are a mystery. Based on estimates from the US coast guard, it would take 15,000 staff to examine all the containers at a port the size envisaged for London Gateway – it's never going to happen.

But computers now control almost every element of the supply chain. Containerisation was not possible without computers to plan it efficiently. In 1957, one container company hired a computer at $100 a minute to calculate efficient routes. Now they track hundreds of millions of containers, each one of which might have hundreds of individual consignments.

"We, as consumers, are changing the way in which we buy things in recent years. We won't go out to the high street or out-of-town shopping centres," says Simon Moore, London Gateway's CEO. "More and more, we're not going to go further than our computer screen. And we expect our goods to get to us within 24 hours."

Predicting what we want may be part of that, as the 'just in time' principle reaches retailing. Technology has already turned the purchase of supermarket wine into the fulfilment of a prophecy; the wines on the Caledon were based on numbers crunched to predict consumption a year in advance, and constantly adjusted to take into account weather, special occasions, and promotional deals.

But while the public-facing internet is a constant subject of scrutiny and debate, the development of the networks and infrastructure which underpin how everything we own reaches us, lies out of sight.

In the The Mirror of the Sea, Conrad saw the future coming into being at the "magnificent and desolate" Port of Tilbury, a smaller port a few miles upstream from London Gateway which, in 1906, then lay mostly empty in anticipation of hosting the "biggest ships that float upon the sea", and which would come into its own within the early years of containerisation.

A similar feeling is present at London Gateway now, an atmosphere of intense industry in wide, empty spaces. It is a testing ground for automated workforces, and the meeting point where ever more elaborate global supply chains combine with networks of astonishing complexity, with the aim of fulfilling consumers' desires almost before they know they have them. The future has been planned, ordered up, packed into boxes and is awaiting delivery.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments