Revealed: How to get ahead at Goldman Sachs

Exclusive: Being a partner at the bank has an almost mythological status, and an internal memo seen by Jim Armitage shows the qualities needed to make it - like charging a pension fund $70m

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The Christmas break approaches but a select handful of Goldman Sachs rainmakers are counting down the clock to New Year’s Day – and a life of prosperity of which they only dared to dream.

For these are the Goldmanites who have just been told they have made the grade as partners – a near-Olympian status that they take on from 1 January. There are 78 of them this year – 78 of the brightest, most ambitious and most driven men and women in the financial world.

Goldman’s partnership-selection process is the stuff of legend in the City and on Wall Street. Once every two years, a pool of potentials is selected, then the candidates are evaluated by every partner with whom they have worked around the world in a process known as “crossruffing” – named after a cunning cardplayer’s move in bridge. The evaluations are, of course, completely confidential. Partnership selection is one of the secret ingredients that give Goldman its edge – that and paying the biggest bonuses on the block, of course.

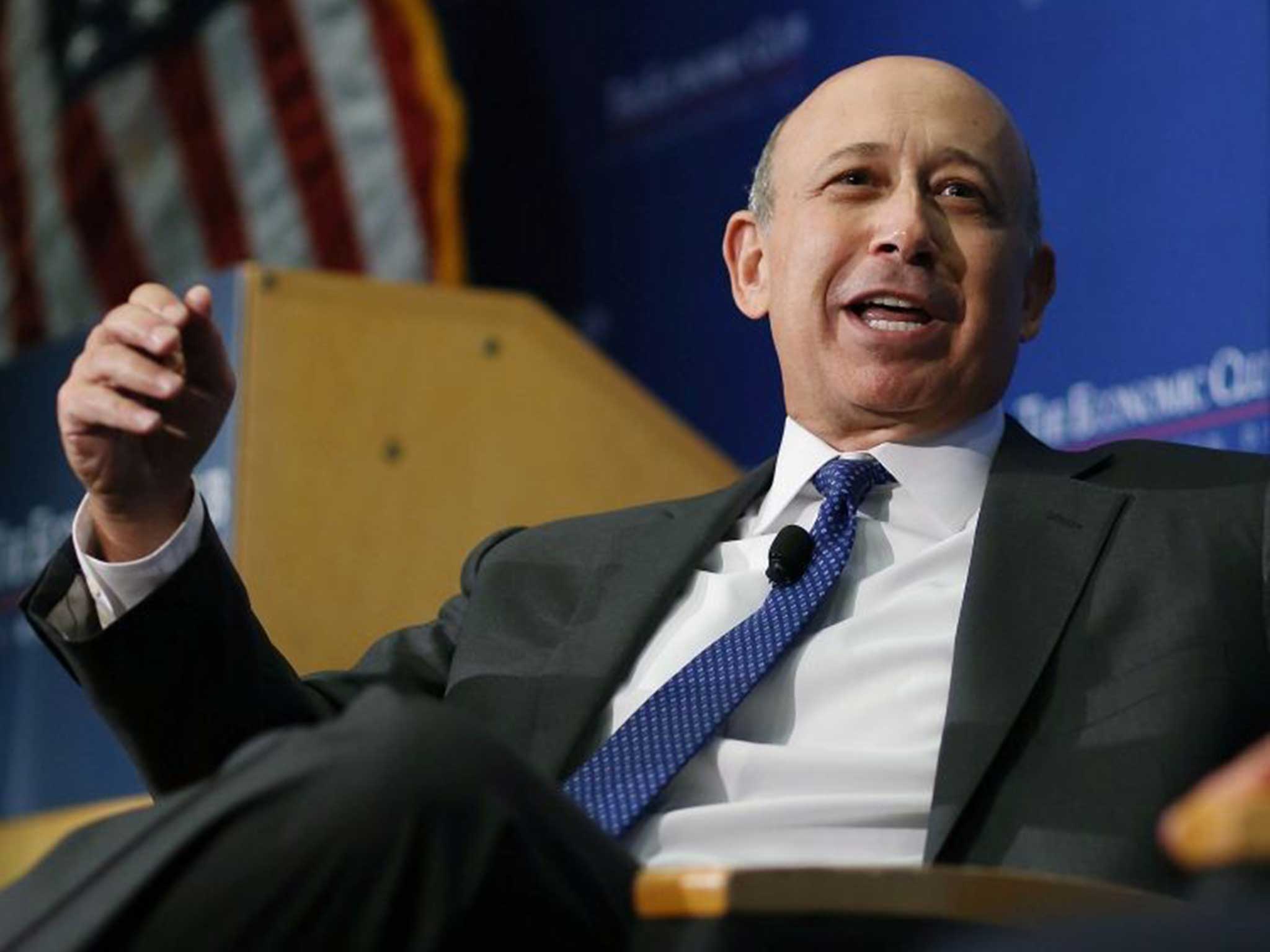

As far as I’m aware, details of the testimonials from partners about their candidates have never been seen outside the firm. So it was quite a rarity to unearth an internal note of one the other week. It’s from a few years back – the 2008 partnership selection to be precise – but the process has remained the same for decades. So thrusting young Goldman executives aspiring to make the grade like CEO Lloyd Blankfein did all those years ago, read on.

The bank stresses that selections are made according to candidates’ leadership qualities, teamwork, appreciation of “the significance of clients” – the usual stuff. But the testimonial memo makes the core message clear: this guy is great because he has an unnerving ability to make money for Goldman Sachs. Big money.

And he makes this cash off the backs of the pension funds of the likes of you and me.

The banker, who is a well-known figure in his niche of the City, joined Goldman in the late 1990s, going on to be promoted to work in various divisions along the way.

“Notable transactions”, the testimonial memo says, included making a killing (my words, not theirs) in helping to reorganise the pension-fund investments of WH Smith and Rolls-Royce not long before the global financial crisis hit.

In the case of WH Smith, the memo says, he helped switch its pension pot from being invested in “cash equity and bonds” to “almost 100% synthetics” – derivatives contracts mainly of the type known as swaps.

The trade was aimed at making the pension fund’s value less prone to being boosted or slashed by the vagaries of the financial markets. At the time, the deal was pretty famous – “innovative” was how pension fund trustees put it. It was certainly an innovation in the amount of money our banker helped Goldman make arranging the trade: “a total P&L [profit] exceeding $70m”, the memo says.

At Rolls-Royce it was a similar story. The pension trustees wanted to take some of the risk out of the fund and used our man at Goldman to do it. The result, to quote the note: “Over several de-risking transactions the revs [revenues] to GS exceed $70m.”

WH Smith and Rolls-Royce seem happy with the deals that their pension trustees did and the way the new-look investments have performed since. Meanwhile, sources say the contracts were put out to tender, and that the pension funds took external advice. Besides which, the liabilities Goldman was handling were many, large and spanning many decades.

But did Goldman really deserve $70m plus in each case? I’m not so sure.

After all, it was not shouldering all of the risk. The way investment banks work on this kind of deal is that they quickly divvy the exposure out among other banks and hedge funds.

I asked around the pensions market about the two transactions. When it came to the WH Smith one, I was told the size of Goldman’s take was something of a cause célèbre at the time. One adviser even said he recalled it had put other pension funds off using Goldman for a while.

So, I asked: how much should Goldman have made? Answers varied from “a few million” to “$25m tops”. It was an unscientific poll, but nobody said “$70m plus”.

You can see why the partner writing the memo is impressed with the banker’s work.

But then, perhaps the Goldman profit is not so surprising when you read on: the note describes in glowing terms how the candidate ensured that his division “is prioritising the highest margin, delta adjusted, products and themes with the right clients”.

How does he ensure that he always sells pension fund clients the product with the highest profit margin for Goldman? By offering clients “solutions providing GS with outsized rates and inflation flow”, the memo says. That means, creating products that will bring Goldman “outsized” volumes of derivatives trades on which it can make big dough.

WH Smith and Rolls-Royce were far from being the only massive pension fund transactions that the banker worked on, the note enthuses. While he was dealing with clients on the Continent, there were four “notable wins” where “combined IRP [interest rate product] revs exceed $70m”, the note says.

The note also talks about how much this banker made for Goldman in his most recent pension fund-related job at the time the recommendation was penned. He started there heading a department at the beginning of 2007, the note says. Since then, “this business has grown under his stewardship by approx. 200% and is now annualising at in excess of $1bn”.

Get your head around that for a minute: the memo seems to have been written in mid to late 2008. Depending on how you interpret that 200 per cent, if the note is accurate, this guy has helped to bring in $500m of new income within a matter of, give or take, 18 months – all on the back of European corporations’ pension funds. How many other businesses in the world rake in that kind of cash? How many bankers can boast of such a performance?

Our candidate is, the memo gushes, “the definitive industry expert”. It adds: “This success has come as a direct consequence of [his] intense commercial focus, creativity, hard work and constant focus on driving a teamwork approach to business to maximise the impact of different skill sets and relationships.”

He has the ability to always be “identifying trends and positioning the institution to monetise them”.

Make no mistake, big corporate pension funds have been a pool of unfathomable “monetisation” for the investment banking industry.

You may remember Greg Smith, the Goldman banker who quit and wrote of his disgust over how the bank treated “muppet” clients.

He spoke of how, as an institution, the bank would target naive investors including pension funds to sell products that would make it big bucks – allegations that Goldman denies.

The investment industry claims such fees as Goldman extracted from the WH Smith and Rolls-Royce deals are a thing of the past, now that pension fund “derisking” deals have become more commonplace.

But try telling that to the managers of the £20bn railway pension scheme. According to the Financial Times, Railpen was last year incensed to discover during an internal sweep through its overheads that it was spending three or four times its annual £70m fund management bill in hidden fees to the City.

This seems such a shocking statistic that surely all of us in company or public sector pension schemes should be demanding of our fund managers: how much of my money are you paying these guys?

But back to our Goldman banker. The testimonial writer concludes his recommendation thus: “Although very committed to the firm, having been a serious candidate [for partnership] in 2006, a failure to promote in 2008 would be taken as a serious message and as such the flight risk is high”.

So, did Goldman’s other partnership gods heed the warning that he’d take his money-making might elsewhere if they didn’t pull him up to their perch atop Olympus?

Of course they did.

Built for profit: How banks ‘manufacture’ swaps

As a rule, the bigger the profit the banks make manufacturing the product that a pension fund is buying, the more likely it is that the employees in the fund are paying over the odds.

I say “manufacturing” because the banks are building a financial product by assembling lots of components from other banks. They may be bets on the future levels of interest rates and bond yields, rather than nuts, bolts and camshafts, but they are components nonetheless.

And as with the most lucrative manufactured goods, the more complex and unique the bankers can make the products, the more they can mask the actual cost (and profit to the bank).

Cynics say this opacity is one of the key reasons why these derivative products, known as “swaps”, have been so aggressively sold by big investment banks over the past decade or so. JP Morgan currently has a notional $68 trillion of derivatives, Goldman Sachs $53 trillion.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments