What is this new UK poverty measure and what was wrong with the old one?

What does this innovation by the Social Metrics Commission measure? And what does it show about UK poverty?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A group called the Social Metrics Commission (SMC) has come up with a new measure of UK poverty.

But why do we need one? Who are the SMC? What does this measure? And what does it show?

Don’t we already have a poverty measure?

Yes, but it’s not official and it’s contested.

New Labour, which set out a target to “eradicate” child poverty and to “end” pensioner poverty, defined poverty (to simplify slightly) as those living on less than 60 per cent share of the median average household income (before housing costs). This became widely known as “relative poverty”.

The Child Poverty Act, introduced by Labour with cross-party support in 2010, committed the Government to reduce the proportion of children living in relative poverty to less than 10 per cent by 2020-21.

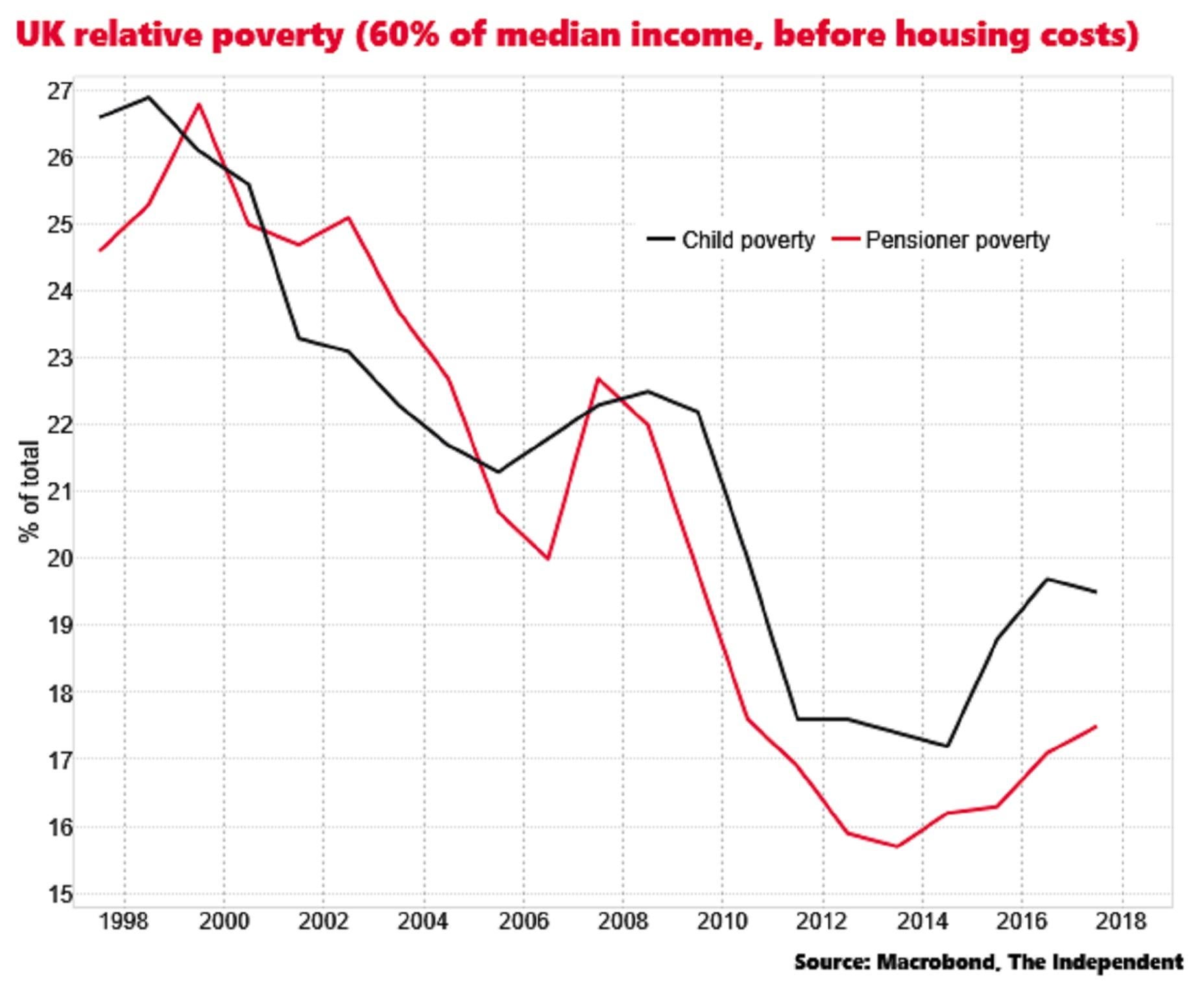

Labour’s redistribution did succeed in reducing relative poverty considerably for both children and pensioners.

For children the relative poverty rate fell from around 27 per cent in 1997 to 20 per cent in 2010.

For pensioners, the rate fell from 25 per cent to 18 per cent over the same period.

What happened under the Coalition?

Protection for the state pension has meant that relative pensioner poverty now stands at around 17 per cent, still down on 2010.

But cuts to tax credits mean, in particular further cuts to support for low-income families with more than two children, suggest that the rate is set to rise by 2022, pushing around one million more children into poverty.

When it became clear that the impact of its austerity policies would be to increase poverty, the Coalition government began to question the New Labour definition.

Conservative ministers argued that this was a crude measure and suggested there are better ways of measuring poverty than simply focusing on household income, such as by taking into account factors like worklessness, family breakdown, debt and drug and alcohol dependence.

Critics accused the Government of moving the goalposts on poverty to avoid political embarrassment or to pull the wool over the public’s eyes about the impact of their welfare cuts.

But even independent experts say that the relative income measure has flaws. For instance, whether one includes housing costs can have a dramatic impact on both the level and trends of the measure. The fact that it takes no account of assets is also not ideal, particular as low-income pensioners, for instance, may have relatively high assets to drawn on. The measure also tends to show a fall in poverty during recessions, as happened in 2008-09.

So, amid this measurement debate, the Social Metrics Commission has now come up with a proposal which it says it hopes will provide a “new consensus” around measuring poverty.

Is the SMC really impartial?

It was established by the Baroness Stroud, a Tory peer and the head of the Legatum Institute, a think tank which has taken a very pro-Brexit line in recent years and has strong links with the Christian wing of the Conservative Party.

Yet a representative of the Joseph Rowntree Foundation was also involved in the production of the report, a group associated with the left.

It has also taken advice from respected welfare reform academics Professor Paul Gregg from the University of Bath and Robert Joyce of the Institute for Fiscal Studies.

What does the new metric measure?

It still measures income but, unlike the existing relative poverty measure, this new one takes some allowance of income from savings and assets.

It also takes into account debt repayment costs and adjusts for the “inescapable” financial costs of disability and childcare.

In addition it uses a three-year rolling average of the median income as a poverty benchmark (rather than a single year) to curb distortions to the measure during recessions that hit most peoples’ incomes.

What does it show?

That the total number of people in poverty in the UK is 14.2 million. That’s around 4 million more than under the current before housing costs relative poverty measure.

The most striking finding is just how prevalent poverty is among disabled people, with the group making up half of the 14.2 million total.

Almost 60 per cent of people in poverty are also in “persistent” poverty, meaning they have been in that condition for at least two of the past three years.

It also suggests far fewer pensioners than currently estimated – around 11 per cent of the total in 2017 – are in poverty.

So is this a better measure which we should all start using?

No measure is perfect, because they are inevitably subjective. And other research groups will, no doubt, critique it in the coming months.

One element of the new measure likely to be controversial is that it suggests child poverty did not, in fact, fall under New Labour but started and ended at around 35 per cent.

Yet the SMC’s effort has won some approval from some credible voices.

“Those who this new proposed measure classifies as being in poverty align much more closely with those who report themselves as being materially deprived, in the sense of being unable to afford a number of specific items,” says Paul Johnson of the Institute for Fiscal Studies, who did not personally sit on the Commission.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments