Forget about speed – make HS2 project’s main selling point its great connectivity

Manchester and the industrial northern cities need HS2 but the real benefit hasn’t been properly explained. A rebranding, one that says very simply what the new service is bringing, and why that matters, is in order

Way back when, I spent part of a summer working at a Manchester law firm. It was the year of the riots, when the courts were cleared early in case the protestors attacked the judges and law officers – it was that bad. In fact, the entire city at that time was pretty dismal. Manchester was a by-word for urban decay, evidenced by empty, crumbling red brick former office buildings across the centre, poor housing and crime. There was a grim air about the place.

If culture is a barometer, the two eponymous football clubs were suffering, and Manchester’s “Madchester” music revolution was just beginning to flourish.

Decades later, and now look. Manchester is named “one of the most exciting cities in the world” by Time Out, “the UK’s most liveable city” by The Economist, and this week, as “the best place in Britain for business outside the capital” by Management Today.

Back in print (Management Today ceased being available in paper form a while ago, to focus on digital, but has now made a return to the traditional format as well as staying online) the magazine heaps praise on the northwest city. It’s the destination of choice for 100,000 students, many of whom settle there as graduates; the UK’s leading regional city for attracting foreign direct investment; home to the largest concentration of private equity firms outside London; a base for world-class research innovation and start-ups, across tech, advanced materials, healthcare analytics, cybersecurity and fintech. The latter has grown 50 per cent in the last decade, five times the national average.

But progress is depressingly slow, and questions remain over whether the second stage of HS2, the section of the project going further north after London to Birmingham, will ever see the light of day.

Add to that, MediaCity UK, the 200-acre development chosen by the the BBC and ITV as the location for many of their operations, and numerous other, forward-thinking initiatives, and you get the picture. Oh, and the cultural life is booming – the music scene is more than alive and kicking, and the football clubs are giants in the game, commercially and on the field.

At the heart of this renaissance – Manchester was always known for its merchant entrepreneurs and inventors, but then underwent an alarming dip – is a strong bond between local government and commerce. In Sir Richard Leese and Sir Howard Bernstein, the leader and former CEO of the city council respectively, it was blessed with having two “can-do” visionaries who understood that businesses represented jobs, which equated to prosperity, and that would serve to attract more businesses – and so the cycle continued. The duo went out of their way to attract inward investment. Very little was too much for them. This, too, in a city that was, and is, Labour, one of the party’s historic stronghold

That partnership, of government and business, should be a blueprint for all UK cities and towns, to be copied and pursued. There is, though, a weakness in Manchester’s armoury, which the survey and an accompanying interview with Andy Burnham, the mayor of Greater Manchester, touches upon.

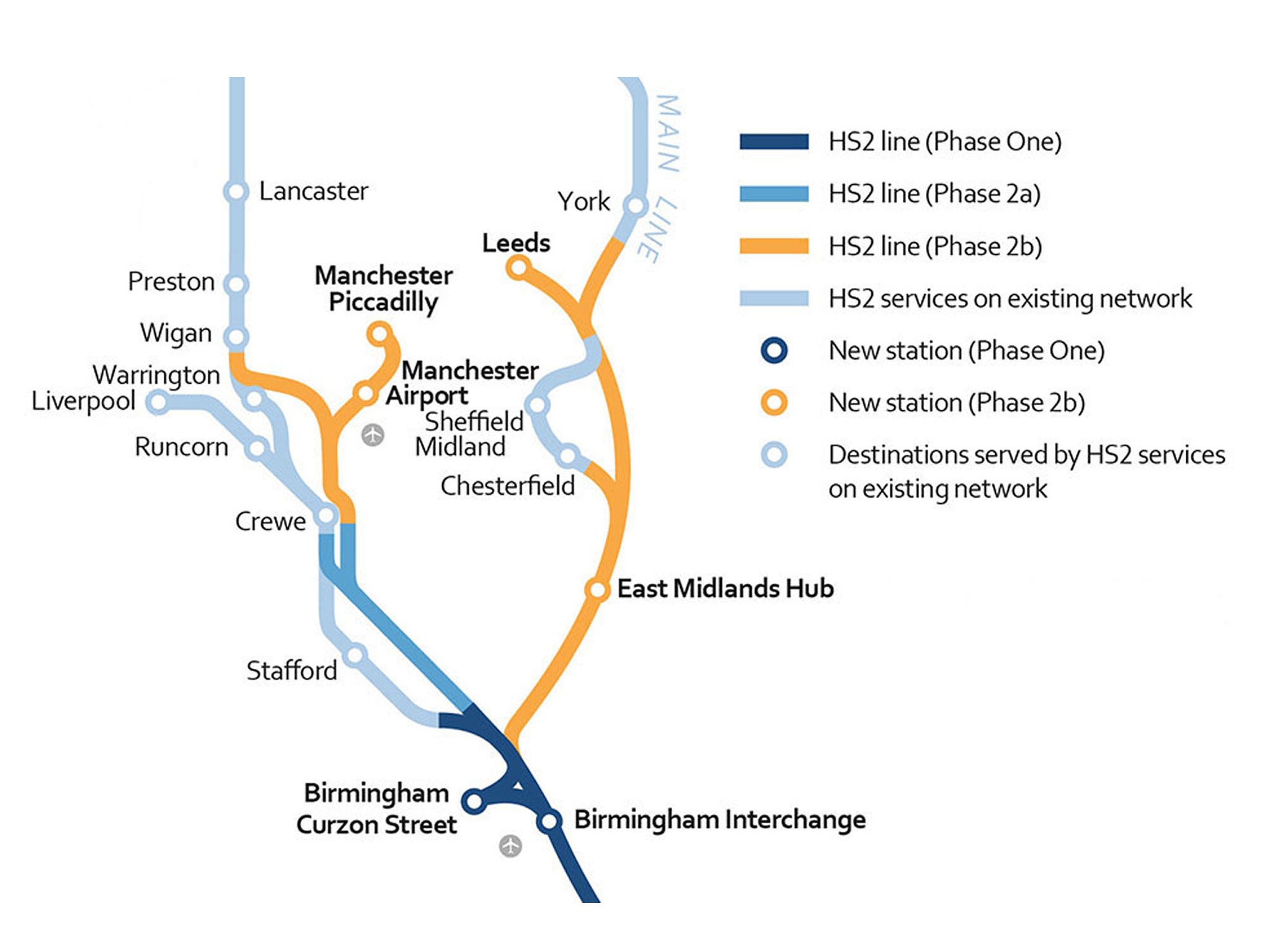

For all its success and promise, Manchester, and its satellite cities and towns, suffers from terrible transport infrastructure. The HS2 rail-link and the Northern Powerhouse Rail project are aimed at going some way towards alleviating the weakness where railways are concerned. But progress is depressingly slow, and questions remain over whether the second stage of HS2, the section of the project going further north after London to Birmingham, will ever see the light of day.

As it happened I was in conversation this week with one of those closely involved in the mammoth undertaking, to create a high-speed service joining London with the northwest and Leeds. Part of the issue, I said, was that the real benefit of HS2 has not been properly explained. Everyone supposes it is about supplying quicker journey times, which it will accomplish, but another benefit, and arguably a more significant one, is the additional capacity it will provide.

In truth, the existing trains between London and the major northern cities are not bad. They’re certainly a lot better than they were. Trimming some minutes off those current speedy times will not make much difference. The real gain with HS2 will be longer trains, with more seats, and running more often, generating more connectivity. Suddenly, those destinations will feel more like a manageable commute than an expedition involving much planning and studying of timetables. Throw into that mix, the Northern Powerhouse scheme to build faster services between the region’s cities, across the Pennines, and the area’s transport provision is transformed.

Coming back to HS2, though. We found ourselves agreeing that the problem lies in that name, that media, politicians and others who need to get behind the plans remain unconvinced about the requirement for extra speed (unlike the original HS1, from London through Kent to the Channel, where there was an obvious requirement because the existing trains were terribly slow). As far as they’re concerned the network from London to Birmingham, and thence to the northern cities, is already pretty quick.

A comparison can be made with Crossrail going east to west through the middle of London. It will cut journey times from Heathrow to central London and to the East End. But that aspect is not in the title

The idea of speed, highlighted by that HS2 moniker, may appeal to grown-up boys who like gadgets and tech stuff, and get off on speedometers, but that is not really what HS is selling. In short, HS2 is sending the wrong message. Unexpectedly we found ourselves concurred that a rebranding, one that said very simply what the new service is bringing, and why that matters, is in order.

A comparison can be made with Crossrail going east to west through the middle of London. It will cut journey times from Heathrow to central London and to the East End. But that aspect is not in the title. People understand it’s a new additional service, crossing London. As a result, they get it, and they don’t quibble. Sure, there have been grumblings about the building costs and delays, but there have been relatively few about the actual need for its construction – and certainly not in anything like the volume that has beset HS2.

It’s a shame that more attention to this early on, that some bright spark thought it would be smart to call the Birmingham and north line HS2, following a successful HS1. Late in the day, a rethink of that HS2 branding might send a better signal.

Chris Blackhurst is a former editor of The Independent, and director of C|T|F Partners, the campaigns, strategic, crisis and reputational, communications advisory firm

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments