Investment: Safe havens for troubled times

Where do investors put their spare funds when banks are no longer regarded as invincible institutions? Sean O'Grady reports

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

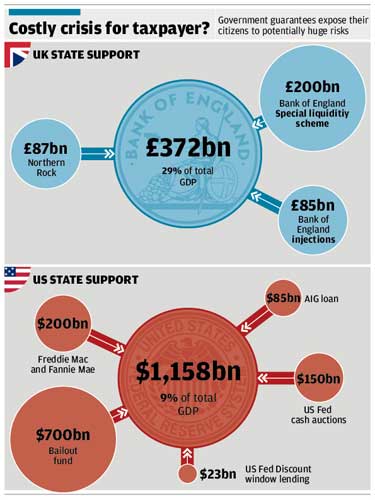

Your support makes all the difference.Not in 70 years or more have the credit markets seen such extraordinary conditions. Hank Paulson, the US Treasury Secretary who is now in the fight of his life to persuade Congress to agree to his bailout plan for the banks, put it most starkly during his testimony on Capitol Hill: "The system is frozen".

The banks will lend to the government, but not to each other. Put into figures, perhaps the most telling is the somewhat abstruse spread between the interbank lending rate, Libor, and the overnight index swap rate, effectively the rate for unsecured lending. This spread has become so stretched that it is now a purely notional figure. Banks simply cannot see as far ahead as a mere three-month timeframe.

In sterling, for example, from a pre- crunch norm of a few basis points this spread has soared to a record high of 154 basis points, or 1.54 percentage points, yesterday.

Or take the so-called TED spread – the difference between what the banks pay and what the US Treasury pays to borrow dollars for three months. This has has widened to 3 percentage points, from 1.14 points a month ago, and is close to a record high since Bloomberg began compiling this data in 1984. These indices are telling us that any bank going out to raise any medium to long-term funding is going to find it tough. Once again, the credit crunch has intensified.

Why? Worries about the Paulson Plan most immediately; worries about the world economy in the medium term, with oddly, to the fore the burden that the Paulson Plan itself will place on the US economy. The Plan promises to take the toxic debts off the banks' books and, thus, strengthen their balance sheets and transform the credit ratings. Any signs that that a shorter-term positive development is in jeopardy is bound to spook the markets. With the Fed promising to rescue them, there is a chance you would lend to a bank; without such a guarantee you would not. And as institutional investors make their judgments, so do retail savers and investors pick up the signals, usually via the share price and generally negative coverage in the media. If the depositors then start to withdraw funds, then the fundingworries, once seemingly remote, become a real, self-fulfiling prophecy. Hence the extreme nervousness.

So what are the banks, and many millions of individuals, doing with their spare funds? First and foremost, the banks are "hoarding liquidity" as they try to repair the damage done to balance sheets over the past year. They want their investments to be as liquid and as safe as possible, and are lending out funds only to the most secure of institutions or investing in the safest of assets – and for the shortest of times; days and weeks rather than months or years. Even commercial paper is doing better, but only at maturities of up to seven days. This time-distortion applies even to such hitherto cast-iron propositions as the government of the United States of America. Investors and banks may not fear that America is actually going to go bust and default, but they are not so sure that the vast issuance of debt under the Paulson plan – $34bn (£18.5bn) sold yesterday alone – and deteriorating prospects for the US economy will prevent a run on the dollar itself. Thus there is a massive preference for short-term Treasury Bills over longer-term Treasury bonds. One month maturity Treasury Bills are indeed so popular that they have seen their yields fall to 0.1 per cent, against a rate of around 1.5 per cent prevailing a couple of weeks ago.

Even hedge funds have suspended their search for yield in favour of a quest for safety. They have reportedly moved around $100bn into "safe havens", simple money-market funds that are traditionally invested in the most conservative of instruments and which are now bolstered by yet another US Treasury guarantee. Gold, the ultimate safe haven, is also experiencing renewed interest.

The anecdotal evidence is that depositors were worried about the money they had in Halifax Bank of Scotland before the Lloyds TSB deal was announced. Northern Rock, now very safe since it was nationalised, has seen an uptick in interest in its products. National Savings too reports more interest. Most tellingly of all, the banks themselves are leaving their money on deposit at the Bank of England, some £6bn recently.

The banks, it would seem, arewaiting for next domino to fall – not that that will restore confidence or end the crisis. Probably quite the opposite. Confidence has evaporated, and the Paulson Plan is the best hope for the world of restoring it.

National Savings and Investments

Since the credit crunch began, the UK's NS&I hasreported an increased level of interest in their products, whichare backed by an unlimited guarantee by the British state. They said yesterday that "It is still far too early for us to see the extent to which the current market instability has affected sales, although we have noticed anincrease in calls to the call-centre."

Bank of England

Despite all its travails, the Bank of England has retained its reputation as a secure home for funds. The UK's banks have put some £6bn on deposit with the Bank, in ultra-safe but low interest accounts. The Bank is now in the unusual position of being able to take back some of the injection of liquidity it undertook during the recent near panic conditions in the market. However The Old Lady will still have to deal with the utter reluctance of banks to lend to almost any entity for longer than a few days or weeks. The challenge for the Bank of England's financial markets team will be how to restore some semblance of normality to the three month-plus market for money.

Northern Rock

They have noted an "up tick" in the flow of funds to their products, including monies form "other organisations": "we've been quite busy in the last week". A year ago it was perceived as the riskiest place for you r money; now it is thought of as, well, rock-solid, it nationalisation endowing it with the same assurances as national Savings. However they also say that their competitive framework prevents them from turning this into an unfair advantage against the other banks.

Treasury bonds

Record low rates for short dated Bills testify to the extreme demand for them. At the height of the panic, a few trades showed investors taking negative returns in exchange for the ultimate security – for the first time since the attack on Pearl Harbour.

US Treasury bill rates fell again this week, with one-month rates briefly dipping below zero, as worries about the bank bail-out caused a stampede for cash and safe-haven assets. This risk-averse shift siphoned credit from the banks, companies and individuals who need it, and pushed risk measures toward record levels. Companies are having to offer much higher rates to entice overnight funding in the commercial paper market, with some offering rates of 6.50 percent – 4.50 percentage points higher than the overnight rate on what banks charge each other on surplus bank reserves.

Money-market funds

These have gone through an unprecedented crisis of their own, with some funds "breaking the buck", or par, so unpopular and undervalued have they become. Now, with another US Treasury guarantee behind them, they have returned to their traditional role as a safe haven in times of trouble. The hedge funds are said to have moved about $600bn of their assets into cash, and of this around $100bn has been siphoned off into money-market funds. US mutual fund managers are also holding near recordlevels of cash; on average around 5.4 per cent of total fund values.

Gold

Traditionally the safest of safe havens, gold also now has the attraction of being a hedge against a weak dollar, which could easily arise if the Paulson Plan fails, with a renewed crisis in the financial system – or if it succeeds, as the burden of US Treasury debt takes its toll on American taxpayers and the wider economy. So, gold seems a one-way bet. Mark Byrne, director of Gold and Silver Investments, says: "Retail demand is extremely robust as evidenced in shortages of gold and silver in the US, India and in east Asia. The world's largest gold refinery, Rand, in South Africa, was cleared out of their entire inventory of Krugerrands in one order by an anonymous Swiss institution." Goldman Sachs and Citigroup are said to be especially keen goldbugs, as is the Bundesbank, the world's second-largest holder of gold after the US Federal Reserve. Some say that the Chinese Treasury, which has $1.8 trillion of US dollar assets and less than 1 per cent of their currency reserves in gold, may warm to the yellow metal.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments