Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The trade unions think we should all be paid more. The latest campaign from the TUC, the union umbrella group, is simply entitled "Britain needs a pay rise". They would think that, of course. After all that's what unions have always done: they lobby for better wages and conditions for their members.

But something is different this time. The unions have a respectable macroeconomic case in favour of higher wages. In recent years an increasing number of economists have reached the conclusion that a rise in average wages might actually help boost GDP and also contribute to the stability of the financial system.

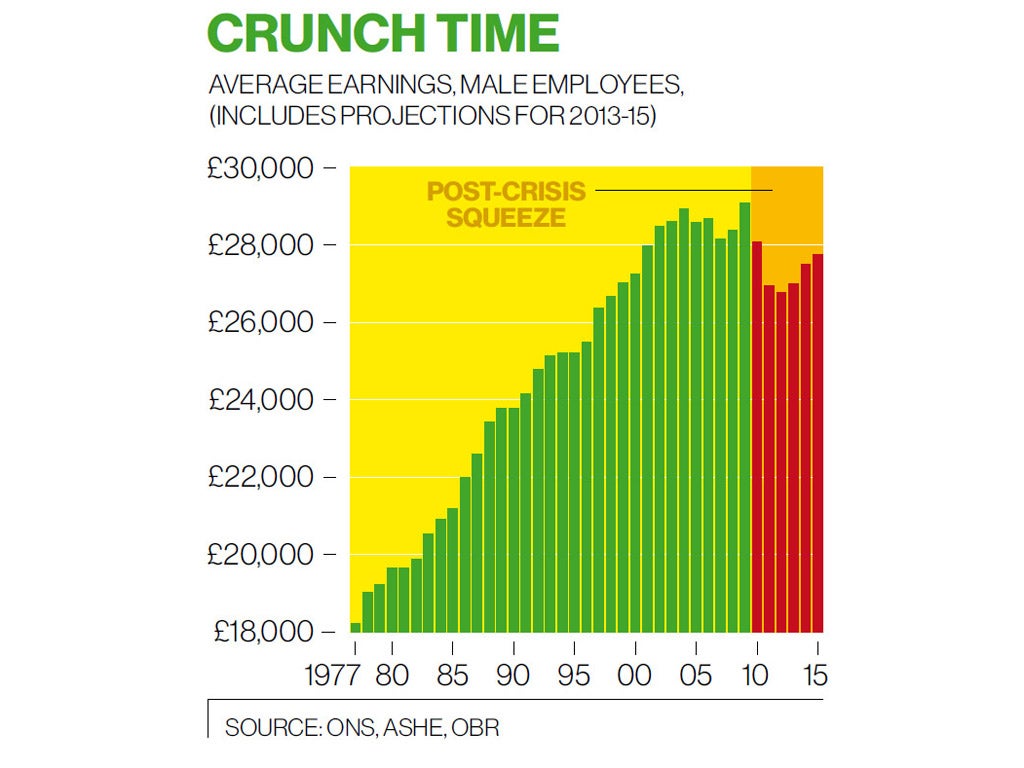

The data clearly show there has been a wage squeeze in recent years. Real wages have been falling since the 2008-09 recession, as nominal pay growth has been weak and easily outstripped by rises in the inflation rate. Indeed, research by the Resolution Foundation suggests the squeeze on pay began long before the financial crisis. The think-tank points out that average median wages for male workers in Britain began to stagnate around 2003, when the economy was still motoring. The lion's share of the growth between 2003 and 2008 flowed into the pockets of the executives of big firms and workers in the City of London.

As the chart shows, wages are also destined to remain stagnant for the foreseeable future under official projections from the Office for Budget Responsibility. Vanishingly few workers are likely to see anything close to the 15 per cent pay rise that MPs are reportedly set to receive after the next election. Company bosses also continue to pull away, with their total remuneration up by 10 per cent last year.

There is a broader trend overlaying this story. The labour share of GDP has been falling since the late 1970s. There is some debate about whether this is a reflection of a rise in self-employment, with some pay growth registered as profits, rather than a collapse in wages. But a similar trend of a falling wage share in GDP has been observed across the developed world. In the West, workers' wages seem to be under pressure.

Does it matter? The conventional wisdom used to be that if wages grew too fast growth would inevitably suffer. But in recent years a number of studies have begun to cast doubt on this assumed trade-off between social justice and economic efficiency. In 2010 two International Monetary Fund economists, Roman Ranciere and Michael Kumhof, wrote a paper putting forward the hypothesis that low average real-wage growth and high inequality in some Western countries, including Britain, drove excessive borrowing by poorer households in the pre-crisis years. This dynamic, goes the theory, created the global credit implosion of 2008. Others have linked weak average pay growth and demand to low productivity growth and feeble company investment since the crisis.

So there is a plausible case that higher average wages would boost aggregate demand and also help to get the economy's wheels turning by encouraging business investment. But how to get there? Many emphasise supply side reforms such as state investment in education to boost skills, which would enable larger pay packets. But the TUC points out productivity growth and wage growth have been decoupled. It prefers a more direct approach, calling for an rise in the minimum wage. It also recommends an rise in union bargaining power, plus curbs on spiralling executive pay. This approach chimes with talk of a shift from the traditional redistributive approach used by post-war governments to combat inequality to "predistribution". In other words: raise incomes directly, rather than topping them up through benefits.

But some counsel caution about predistribution, saying many households in the lower and middle region incomes are heavily supported by tax credits and that people in these groups would only take home a quarter of every extra pound they earned. "It's quite hard actually to help people by raising hourly pay over time," says James Plunkett of the Resolution Foundation. "Pay rises tends to benefit people on high incomes more".

How to secure that national pay rise is likely to remain contested. But the idea Britain needs higher wages to underpin a sustainable and robust recovery certainly has the wind in its sails.

Case study: Few increases but strikes are too expensive

Ned Hindley, 50, started work at a manufacturing firm in the North East in 2000 on a salary of £22,000 a year. Until the financial crisis he received pay rises above the rate of inflation, but in 2008 his bosses imposed a six-month freeze. "Six months turned into 12 months, then it went to 18 months," says the married father-of-two. "Since then I've had rises but they've been under the rate of inflation."

But Mr Hindley considers himself fortunate compared with some of his colleagues. "If you're in engineering you get paid a bit more than the shop-floor operatives," he says. "We're still getting the opportunity of overtime to carry out maintenance. But the lads on the manufacturing side don't have that. They've struggled."

Industrial action to demand higher wages is, however, off the table. "The problem is that going on strike, you can end up losing a lot more money than you can get by just accepting it. Plus there's the worry of your job," says Mr Hindley.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments