How Honda lost its mojo – and the mission to get it back

Senior members reveal how the car maker stifled creativity and innovation

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The driver punched the air as his red and white Honda McLaren roared over the finish line. It was Suzuka, Japan, 1988, and Ayrton Senna had just become Formula 1 world champion for the first time. The McLaren racing team and its engine maker, Honda Motor, were unstoppable that year, their drivers winning all but one of the 16 grand prix races.

Off the track Honda had been tasting success, too. In the 1970s, its engineers had raised the bar for fuel efficiency and cleaner emissions with the CVCC engine. In the 1980s, as its engines were propelling Senna to multiple victories, the Civic and Accord cars were redefining the American family sedan. In 1997, Honda became one of the first carmakers to unveil an all-electric battery car, the EV Plus, capable of meeting California’s zero emission requirement.

Jump forward almost 30 years from that Senna moment and Honda is flailing. On the racetrack, the Honda McLaren partnership is in trouble: The team is without a single win this season, and McLaren is losing patience with its engine supplier and speaking of a parting of the ways.

On the road, the Honda fleet has been dogged by recalls. More than 11 million vehicles have been recalled in the United States since 2008 due to faulty airbags. In 2013 and 2014 there were five back-to-back recalls for the Fit and Vezel hybrid vehicles due to transmission defects. Honda has lost ground in electric cars to Tesla and others.

“There’s no doubt we lost our mojo – our way as an engineering company that made Honda,” chief executive Takahiro Hachigo says.

Hachigo joined Honda as an engineer in 1982 and became chief executive in June 2015. Now he wants to revive a culture that encouraged engineers to take risks and return to a corporate structure that protected innovators from bureaucrats focused on cost-cutting.

To help him achieve this, he says he has tapped into the ideas of a small group of Honda engineers, managers and planners.

This group is modelled on the freewheeling “skunkworks” teams that drove aircraft development at Lockheed Martin, computer design at Apple and self-drive technology at Google.

In interviews, more than 20 current and former Honda executives and engineers at the company’s facilities in Japan, China and the United States recount the missteps that they say contributed to Honda’s decline as an innovator. They also reveal new details of the firm’s efforts to rediscover its creative spark.

They say Honda had become trapped by Japan’s “monozukuri” (“making things”) approach to manufacturing. This culture of incremental improvement and production line efficiency, called “kaizen”, served the company well in the decades after the Second World War, they say, but today’s challenges – electrification, computerisation, self-driving cars – demand a more nimble and flexible approach.

Most importantly, they say, over the past two decades company executives in Tokyo were given too much control over research and development. In their view, this led to shareholder value being prioritised over innovation. There was a reluctance to draw on talent from outside Japan. In its quest to deliver for shareholders, Honda sought to maximise volume and profit and match the product range of its main Japanese rival, Toyota.

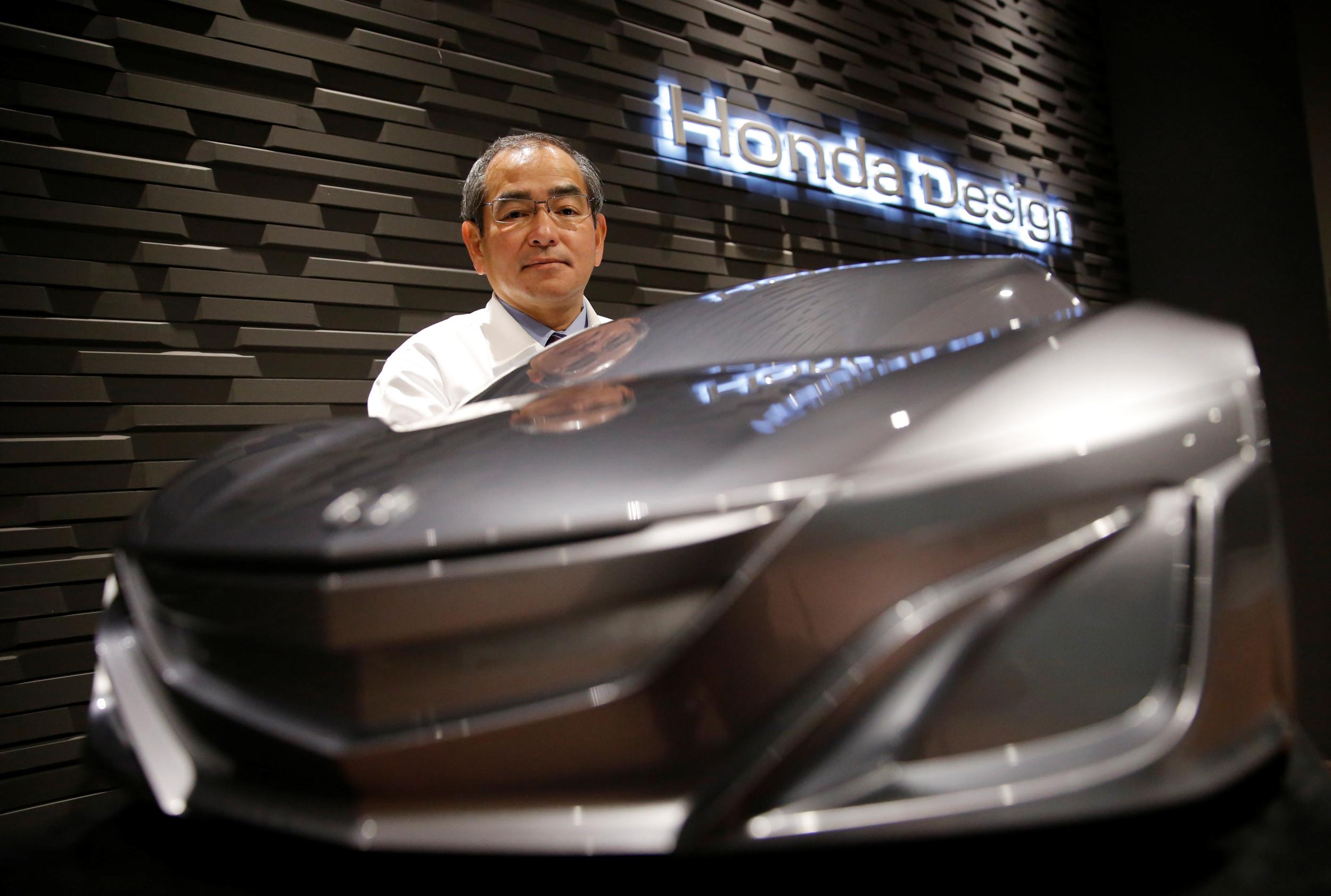

“The upshot was, as we obsessed about Toyota and beating it in the marketplace, we started to look like Toyota. We started to forget why we existed as a company to begin with,” Honda R&D President and chief executive Yoshiyuki Matsumoto says.

Honda’s revenues have grown strongly since 2000 and its operating margin stood at 6.0 per cent in the financial year ending 31 March 2017, compared with 7.2 per cent at Toyota. But Honda’s cars have slipped down quality rankings, from seventh in market research firm JD Power’s initial quality study in 2000 to 20th in 2017.

Honda Civic loses its shine

Striving to satisfy shareholders meant controlling costs. Honda’s chief executive from 2003 to 2009, Takeo Fukui, broke with the firm’s tradition of giving tech managers discretion over how to spend the roughly 5 per cent of revenue allocated to the tech arm, according to the current and former Honda executives and engineers.

When Takanobu Ito replaced Fukui as chief executive in 2009, he further tightened control over the design phase. He did this, the sources say, by moving several senior posts in the tech division to corporate headquarters in Tokyo from the research and development unit, whose main car centre is near Utsunomiya, an hour north of the capital city by bullet train. Ito and Fukui did not respond to written questions.

Honda’s popular Civic car was one of the casualties of these changes, according to the engineer in charge of the model’s redesign beginning in 2007. With a reputation for outstanding engineering, reliability and affordability, the Civic was one of Honda’s top selling cars.

“Right from the get-go, the programme was about making cost savings in real terms,” the chief engineer for the redesign, Mitsuru Horikoshi, says.

To that end the global car business unit, headed at the time by future chief executive Ito, and the tech division decided that the redesigned Civic would use many of the same components and systems as the previous model, including the front and rear suspension systems and the front section of the car.

Civic engineer Horikoshi had finished a first design setting down the basic engineering points by February 2008 and a more detailed design by April. When rising gasoline, steel and other prices pushed up manufacturing costs by between $1,200 and $1,400 per vehicle, Horikoshi’s team refined their design to improve the car’s fuel economy. In early July 2008 they sought management approval for their plan at a meeting in Torrance, California, Honda’s US sales headquarters.

Global car head Ito said he would review the design overnight, Horikoshi recalls. The next morning, Ito came back and told the team to make the car smaller and cheaper to produce, and complete the redesign by the end of that month.

“With one blow of a cost chopping knife, Ito basically told us to take our design back” to the first plan. “It’s just unheard of. It was unprecedented,” Horikoshi says.

To meet Ito’s specifications, Mr Horikoshi used cheaper materials and made the car smaller, cutting its length by 45mm and its width by 25mm. He also reduced the wheelbase, the distance between the front and rear axle, by 30mm.

A former leader of Honda’s R&D unit says the firm “lapsed deeper into a bunker mentality, and that translated into our products. It was cut, cut, cut, and it cheapened our cars”.

By the end of 2008, Horikoshi’s team was wrapping up the Civic design. Half a year behind schedule, they were still $200 short of the cost target per car.

“I already had my pants down to my ankles – nothing more to shed,” Horikoshi says.

When the 2012 model year Civic went on sale in 2011, it was met with a barrage of criticism. Influential US magazine Consumer Reports dropped the car from its recommended list for the first time since it began rating vehicles in 1993. It criticised the new Civic for a poor quality interior and uneven ride.

R&D chief Matsumoto says the episode is a lesson that creativity should not be sacrificed on the altar of shareholder value. During previous assignments for Honda in Thailand and India, Matsumoto says, he had looked at headquarters from afar and recognised a lack of creativity there.

“We have to be allowed to go wild at times. If you operated a technology centre only from an efficiency perspective, you’d kill the place. This is exactly what happened at Honda. We don’t want headquarters people telling engineers what to do,” he says.

Honda went back to the drawing board. The redesigned model that replaced the 2012 Civic was named the 2016 North American Car of the Year by car journalists.

Ito and Fukui did not respond to questions from Reuters about the Civic. A former senior executive says the decision to reduce costs was taken in the context of a global economic slowdown. Honda’s chief spokesperson, Natsuno Asanuma, says the focus on shareholder value under previous management was “for the sake of the company’s future”.

James Chao, Asia-Pacific chief of consultancy at IHS Markit Automotive, says Honda failed to keep up with developments in suspension and transmission during Fukui and Ito’s tenure, but the firm was doing well enough financially, which masked the problem.

“One could argue that Honda nonetheless performed nearly as well with the lower investment, but it was hard not to see that they were no longer leading in some technology areas,” says Chao, who is based in Shanghai. Honda’s rivals, such as Ford, were not reining in costs to the same degree, Chao says.

At the same time as Honda bosses were tightening the budget for the 2012 Civic, they were also looking for savings in research and development.

Other car firms were investing heavily in green technology, an area where Honda had already established itself as a leader with the unveiling of its EV Plus battery car in 1997, one of the first electric vehicles from a major carmaker. But just as its competitors were investing more, Honda began holding back.

Fukui, who became chief executive in 2003, felt Honda was engaged in too many areas of research, four current and former executives and engineers say. As a result, Honda scaled back work on plug-in battery electric vehicles and put its faith in the hydrogen-fuelled car. By the time Honda turned back to plug-in cars in the late 2000s it had already lost several years to its competitors. Honda finally came up with a competitive plug-in car in 2013, 16 years after its original electric vehicle. It is still playing catch up with the likes of Tesla.

Mr Fukui did not respond to questions. Two former engineers say Mr Fukui was calculating that advanced battery technology would become commoditised and so Honda would be able to buy it in if necessary. This assumption was correct, the former engineers say.

Frustrated talent

For too long Honda has overlooked the potential of its workforce outside Japan, and that has harmed the firm, says Erik Berkman, a former head of Honda’s technology unit in the US, the carmaker’s biggest market.

Honda’s management team, board of directors and operating officers were until recently all male and Japanese. The company named its first foreign (Japanese-Brazilian) and first female board members only three years ago.

In the fall of 2013, Berkman gave a speech in Motegi, Japan, at a meeting of Honda engineers and researchers. His message was clear: It was time for Honda to tap the brainpower of all its engineers. Research staff in the United States, some of whom had worked at Honda for more than two decades, were being treated like students, Berkman told an audience of roughly 500, including the company’s top leaders.

“We don’t want to be ‘indentured servants’,” Berkman says. “My attitude is: ‘This is my company too.’ Increasing diversity within Honda, and specifically Honda R&D, is our path forward.”

Berkman says many capable engineers and researchers in the United States had left Honda over the years out of frustration at being disregarded. “Many associates (in the US) felt Japan bosses were too controlling and unwilling to take on what we thought were reasonable risks,” he says.

Many of those in the audience at Motegi, including senior managers, congratulated him on his speech, according to Berkman and two other participants at the meeting. But shortly afterwards he was demoted from his role as Honda’s North American technology chief and reassigned to a more junior planning position in another unit.

“Maybe it had nothing to do with the speech. In my mind, it did. I kind of bit the hand that feeds me,” he says.

Honda declined to comment on the episode.

Berkman says he decided to retire from the company where he had worked for 33 years. “I had been planning for retirement for many years and felt this was the right time to go,” he says.

Speaking to Reuters, R&D head Matsumoto acknowledges that Honda’s technology and research staff lack diversity.

“You only see Japanese faces in the place,” he says. “But we are repositioning tech centres in places like the United States, Thailand and China to function more like satellite centres to our central labs in Japan, so as to encourage exchanges of people. Pureblood-ism doesn’t cut it. That’s our growing consensus.”

Skunkworks

Japan’s manufacturing sector, especially the car industry, prospered in the post-war era by harnessing monozukuri principles of steady design improvement and lean manufacturing that encapsulate the Japanese reverence for craftsmanship in manufacturing. The aim was to produce vehicles with one-third of the defects of mass-produced cars using half the factory space, half the capital, and half the engineering time. Those efforts, honed over years, elevated the quality and reliability of Japanese cars to the point that by the 1980s consumers in the United States began choosing Japanese cars over US made vehicles.

Today the industry is facing new challenges, however. Artificial intelligence and self-drive cars are forcing carmakers to rethink the way they design and produce vehicles.

“Japan’s car industry emerged in the post-Second World War era by chipping away day in day out to improve products. That’s not going to cut it in the face of the rise of disruptive self-drive, connected car technology and electrification,” Matsumoto says. “The new era calls for a totally new approach.”

Some changes are under way at Honda to address these disruptive forces. These include moving tech management jobs out of Tokyo to give the technology division more autonomy.

Honda has struck deals with third parties to accelerate progress on its smart-connected electric car. These include an agreement with Hitachi to develop and produce motors for plug-in electric cars and a deal with General Motors to produce hydrogen fuel cell power systems in the United States. Honda is also in talks with Google to supply vehicles to jointly test self-driving technology.

A key force for change inside the company is the small group of engineers, managers and planners who are working quietly behind the scenes to revamp the company, according to Hachigo and Matsumoto.

The group’s existence is little known inside the company. The team works out of Kyobashi, a neighbourhood near Tokyo Station. Honda bosses declined to share the identities of its members.

They did share some of the ideas it is advocating. These include streamlining Honda’s product development process, which became bloated as the company got bigger, and developing underlying technologies for a range of vehicles to develop cars more efficiently and respond more quickly to changes in customer tastes. The group also wants to increase the use of virtual engineering tools, such as computer aided design, to speed up development, and it is working on an improved design for plug-in battery cars.

Matsumoto is hoping the group will be transformative. But he doesn’t expect change to be instant.

“Almost always change – any change – starts on the fringes,” he says. “This group is evidence that we still somewhere inside this company have the mojo we lost. There is that DNA left in us.”

Reuters

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments