Google becomes Alphabet, but what does it spell for investors?

Google's corporate restructuring is intended to make the tech giant more transparent and accountable. But not everyone in the market is convinced

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When Larry Page, Google’s co-founder, unveiled its new corporate structure this week, he harked back to a letter he wrote 11 years ago, explaining that the tech giant “is not a conventional company”.

That is undeniable. After all, how many companies have so many fingers in so many different pies? Yet from an investment perspective this week’s restructuring represents something of a concession to conventionality.

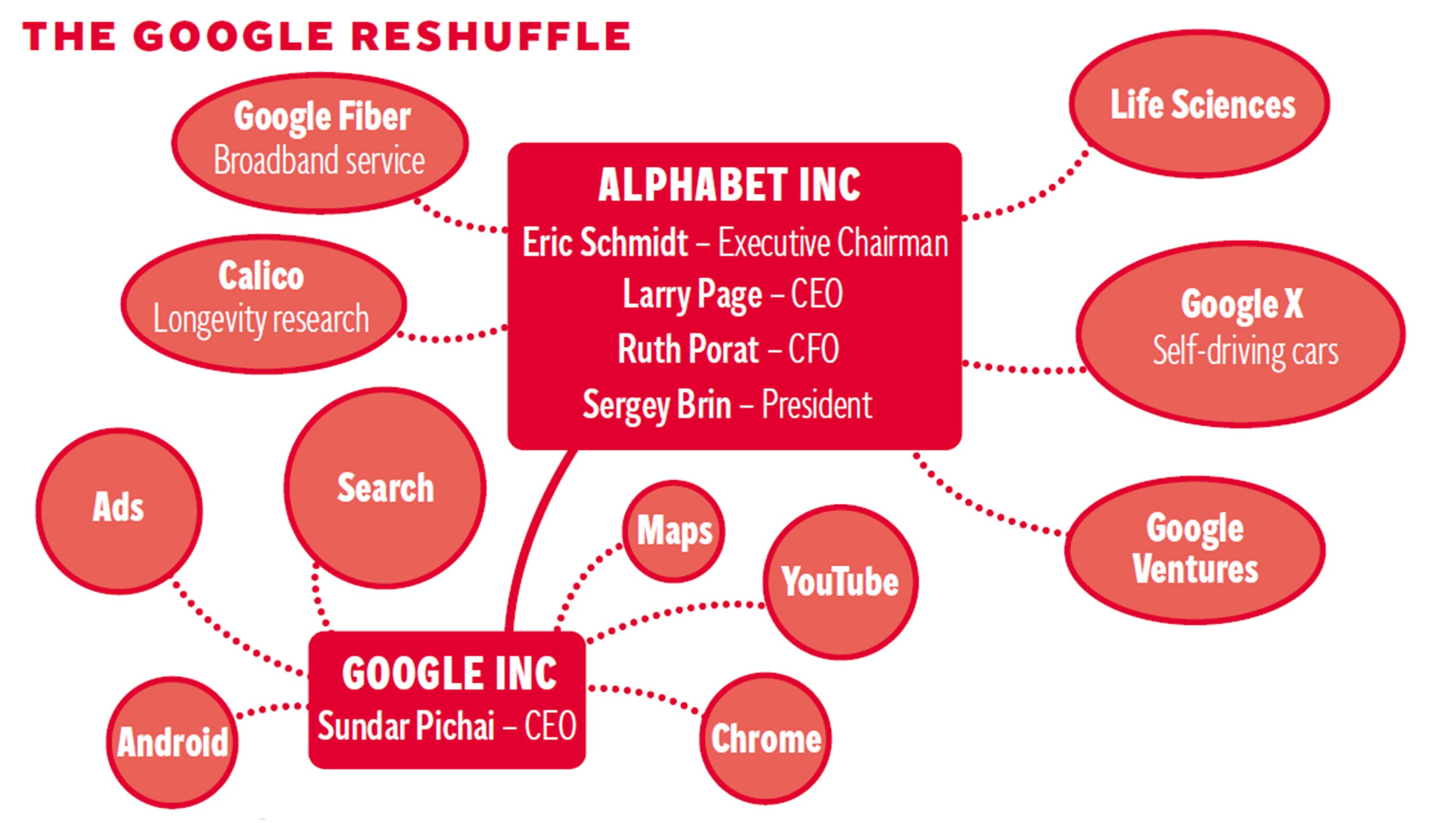

Mr Page revealed that Google is creating a holding company called Alphabet to separate the “blue sky” start-up businesses – the driverless cars, the drones and so on – from the stalwarts of Google’s web work – the search engine, the advertising arm, maps, YouTube and Android.

Its shares will continue to trade on Nasdaq under the GOOGL and GOOG tickers and Alphabet will still generate almost all of its profits from Google.

Nothing fundamental has changed regarding the company’s operations. But investors will be dealing with a simpler structure which Mr Page says will make Google “cleaner and more accountable”.

Many big companies have created holding companies; examples include Centrica, owner of British Gas, and IAG, which owns British Airways. The structure gives a company more flexibility should it decide to change the focus of its main business.

In Google’s case, it is a way of splitting apart the internet business and the so-called “moonshot” divisions, which include the life sciences division Calico, Google X, Nest Labs, Google Ventures and Google Fiber.

Investors think that by next year they will be able to see a breakdown of the separate businesses and gauge how much a business such as YouTube makes – the video site’s money-making credentials have never been unveiled. Creating the holding company could also make it easier to spin off the more speculative units should they fail to bear fruit.

The move will appeal to traditional investors that would rather see solid profits than blue sky potential.

Richard Windsor, an analyst at Edison Investment Research, says the restructuring should bring “some improved visibility and flexibility” to Google.

“This will provide investors with better visibility in terms of the performance of the core business and how those profits are being invested for the long term,” he adds.

Nicolas Ziegelasch, head of equity research at Killik & Co, said a greater focus on the main Google business will benefit the shares, “without the distraction of the number of highly speculative ventures being pursued”.

The early reaction from investors suggests he is correct. Google’s shares rose by about 5 per cent after the announcement to trade close to their all-time highs, valuing the tech behemoth at $466bn (£300bn).

Perhaps the biggest change in the whole shake-up is that Sundar Pichai will become Google’s new chief executive, with Mr Page becoming CEO of the new umbrella group and co-founder Sergey Brin taking on the role of Alphabet president. Mr Pichai, who was born in India, is currently product chief at Google, where he has worked on Chrome, Google Drive, Gmail and Google Maps since 2004.

With Mr Page’s sights set on new ventures – “Sergey and I are seriously in the business of starting new things,” he says – the call to appease investors may have come from the recently appointed chief financial officer, Ruth Porat.

The former Morgan Stanley executive swapped Wall Street for Silicon Valley this year and will manage the finances of Alphabet, keeping tabs on the outlandish projects of founders Mr Page and Mr Brin.

The vast sums needed to get such early-stage projects off the ground have in the past put off some Wall Street investors.

Bolko Hohaus, who manages the Lombard Odier Technology Fund, says that despite some uncertainty about the appointment of Mr Pichai, he is reassured by the continued presence of Ms Porat.

Mr Hohaus is also buoyed by the fact that the non-core businesses will no longer weigh on the Google “investment case”.

He adds: “We do not yet know the exact financials of the non-core businesses but if you attach zero value to them instead of the negative value currently priced in, we get to significant upside.”

Janice Wall, a partner at the law firm Wedlake Bell, notes that if Google were a UK company it would need shareholder approval to enact such a restructuring.

“Investors generally cannot be forced to exchange their stock or shares in another company without their consent,” she explains. Google already has a dual share structure, with the founders controlling 52 per cent of the voting power. And Richard Windsor of Edison adds: “I think this shortcoming will mean that when things go wrong, the problems will last much longer than they would if shareholders had the power to intervene,” he says.

“I have been a big advocate for Google for the last two years but I think the time has come to think about putting at least some of the money elsewhere.”

Not everyone is convinced that Alphabet spells improvement.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments