From Swindon to the Solar System: UK Space Agency aims to capture 10 per cent of the industry

It’s easy to laugh, but Britain is making steady progress in the space race. And with £40bn up for grabs, we should take it seriously

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The John F Kennedy Space Centre in Cape Canaveral, Florida, is to many people the symbolic home of space, the spot where a generation watched Nasa launch Apollo 11 to put the first man on the moon.

But the home of the UK’s space economy is less memorable: an office block in Swindon. The Polaris building near the train station is home to the UK Space Agency, a three-year-old government quango tasked with capturing 10 per cent of the global space industry by 2030, equivalent to £40bn.

David Willetts, the minister for Universities and Science, is also hoping that investment in the space sector, which includes everything from satellite televisions to rockets, will pay dividends for the UK economy.

Yesterday, in Glasgow, Mr Willetts reaffirmed the Government’s commitment to the sector at the UK’s second Space Conference, announcing £60m funding for the next-generation rocket engine Sabre, claiming that the technology could “revolutionise access to space”.

The industry contributes £9bn a year to the UK economy, employs almost 29,000 and has grown at an average rate of 7.5 per cent since 2008.

Mr Willetts established the UK Space Agency in April 2010 with the aim of propelling Britain to the forefront of the growing space industry, consolidating all of the UK’s civil space funding into one body.

So, three years in, how has it fared?

“It’s had a fairly big impact,” says Jeegar Kakkad, chief economist and director of policy at ADS, the industry body for aerospace, defence and security. “It’s got a £250m budget, which is substantial to focus on one sector.”

“We’re investing in basic science and new technology,” says the chief executive of UK Space Agency, David Parker. “In Europe we’re the second largest space science organisation – for exploring the universe we’re second only to Germany. We’re number one in telecommunications investment.”

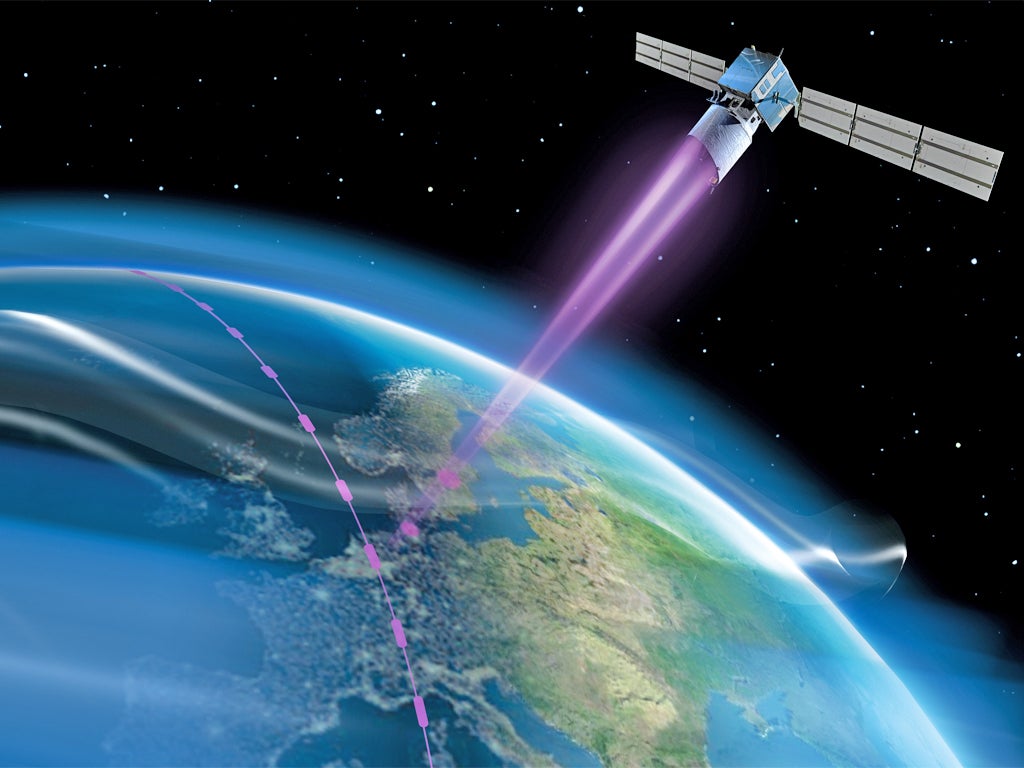

While futuristic rockets like Sabre and PayPal co-founder Elon Musk’s Space X business capture the public’s imagination, it’s the less glamorous areas like satellites and infrastructure in which the UK excels. Firms such as Inmarsat, Surrey Satellite Technologies and Avanti are market leaders, providing the backbone for everything from satellite broadband to tracking ships.

“It’s the modern day roads and rails network – it’s infrastructure, you use it for everything,” says Mr Parker. “Supermarkets decide whether to put hot chocolate or ice cream on the shelves depending on the weather forecast and that depends on the satellites. It’s all part of everyday life.”

But investment in projects like Sabre rocket engines is vital to help the industry maintain its position, as the UK currently relies on other countries to carry out launches. “The UK is playing catch-up. Given the gap we’ve got, we have to be more innovative in the way we’re closing that gap,” says Mr Kakkad. “We’re behind the US especially in terms of the range of services they can offer in getting things into space.”

But the investment push could be a gamble. A survey of the sector last year by the UK Space Agency found a third of firms said the biggest challenge they face is a lack of demand.

“The single biggest barrier is people realising how much you can use space in everyday life,” says Mr Parker. “You can use space data to improve crop yield in farms, to decide where to put your wind farms in the North Sea and monitor them successfully, and to monitor ships, tracking them, making them safe from piracy.”

The Government is doing its best to tackle this lack of awareness. The UK Space Agency has opened a centre in Hull showcasing to industries how they could utilise satellites and space infrastructure.

Meanwhile, ministers have been banging the drum for British space firms on overseas trade missions. Earlier this year David Cameron helped Surrey Satellite Technologies to sign a deal to design and develop satellite system in Kazakhstan.

The “upstream” aspect of the sector – satellites that go into space and the research that goes into them – also makes up a relatively small proportion of the sector.

The headline £9bn yearly contribution to the economy includes everything from insurers working in the field to satellite TV firms like Sky – and it’s “downstream” firms like this that make up 89 per cent of the sector’s revenue.

“Part of the reason why the downstream market is so big is the rapid expansion of Sky boxes and Freeview and TeVo,” says Mr Kakkad. “Those technologies rely on satellites. That will only expand with the advent of internet-capable TV.”

The UK’s space industry may not be very sexy, but at least it looks like it has a future.

Stars in their eyes: A satellite specialist

It may sound a touch parochial but Surrey Satellite Technologies is, according to David Willetts’s speech yesterday, the UK’s “most successful single university spin-out”. It is, indeed, the world leader in making and operating small satellites, controlling 40 per cent of the market.

Founded in 1985 as a spin-off from the University of Surrey, it pioneered “commercial off-the-shelf” satellite technology, taking existing consumer technology and adapting it for space travel. Prior to this, technology was custom-built for space at huge expense and over long periods, often being obsolete by the time of completion.

The company, based in Guildford, specialises in disaster monitoring, using its satellites to map earthquakes and floods. Aerospace giant EADS Astrium bought a controlling stake in 2008 while space entrepreneur Elon Musk also has a share.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments