Britain’s climate defences need a flood of cash

Current investment for adapting to climate change is woeful, officials tell Anna Isaac

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Prepare. Act. Survive.

That is the advice of the Environment Agency when it comes to climate change. But is the country prepared?

Britain has woefully underfunded climate adaptation efforts, leaving its infrastructure at the mercy of extreme weather events, officials and experts warn.

July has been a month of floods, heat, and floods again. Recent days have offered a sharp reminder that the weather is becoming harder to predict, and its toll is set rise further in the years ahead.

Net-zero pledges to reduce carbon emissions have started to cut through with the public, as they face significant changes to their homes and lifestyles.

But the problem of actually living with climate change is often treated as the Cinderella of the climate story, even if its sudden, sharp effects have never been so stark.

That is the case even if attempts, such as the Paris Agreement, manage to curb the rise in global temperatures to 2C, or even 1.5C.

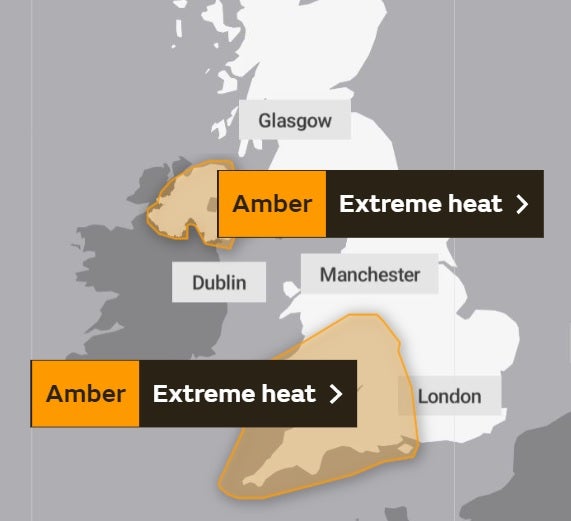

Last week, the Met Office issued its first amber extreme heat warning. Images of flooding tube stations on Sunday followed hot on the heels of death and destruction in Germany and Belgium.

While Britain has not seen the level of damage recently endured by its European neighbours, it is only a matter of time, those tasked with managing the impact of climate change believe. That means the government needs to spend money at unprecedented level, if it is to mitigate the economic devastation of extreme weather.

Floods in the past 20 years have cost insurers billions of pounds, rendered many homes uninsurable, and devastated communities. Meanwhile, extreme heat is a silent killer, with deaths potentially causing an economic blow of £323m a year by 2050 with some estimates as high as £9.9bn, according to one estimate from the Climate Change Committee (CCC). And land prone to flooding is still being used to build homes.

But that’s in part due to a fundamental misinterpretation of the probability of flooding and other extreme weather events, according to Allan Beltran-Hernandez, a fellow in environmental economics at the London School of Economics.

People often think “that a one in 100-year event means that another one won’t happen for another 100 years. But the probabilities are independent of each other.” So if an area experiences the worst flooding its seen for century one year, that makes it no less likely that the following year won’t also face floods that are just as bad or worse.

A spokesperson for the Environment Agency, which covers England, told The Independent that it was investing “record amounts” to help protect communities from the threat of flooding. But it added that “further investment” will be needed in order to be “more resilient to a changing climate”.

But there is a problem, officials agree off record: no one even knows how expensive this problem of adapting to climate change is. The Environment Agency does not know how much to ask for.

There is no number that can readily be found to illustrate the total cost of climate change to the UK, explains Kathryn Brown, head of climate adaptation at the CCC, a statutory independent body set up under the powers of the 2008 Climate Change Act. It is meant to advise the government on emissions reduction targets and readiness for the impacts of the climate change emergency on the UK.

“The reason we don’t have it is largely just because the government hasn’t funded a study with enough resources to find out what that number is,” says Brown.

Brown tries to quantify the risks facing Britain from climate change and measure those against the efforts to mitigate those risks. Every five years the government has to publish a climate change risk assessment. The latest, produced in May this year, had a score card for the impact on infrastructure in the event the world average temperate by 2C or 4C. Using a range from Very High, costing billions a year to Low, costing less that £10m a year, the scorecard makes for troubling reading.

The government should prepare to spend billions each year by 2050 to defend key infrastructure from flooding, the report found. Temperature rises will bring both too much and too little water at times. The report predicted costs of at least hundreds of millions each year to try and manage risks to public water supplies from water shortages.

It has already spent more on flood defenses, £5.2bn for the next six years, than it has on its Levelling Up Fund, of £4.8bn up to 2025. Yet that is not even going to scratch the surface of the adaptation required, experts say. And that is only aimed at tackling flooding and not its combined impact along with issues like extreme heat.

In separate report to parliament published in June 2021, the CCC said of government efforts that “overall progress in planning and delivering adaptation is not keeping up with increasing risk”.

“The UK does not yet have a vision for successful adaptation to climate change, nor measurable targets to assess progress,” the report says, adding that this “stores up costs for the future.” The CCC’s advice to government has repeatedly gone “unheeded”.

But while the government hasn’t put a number on the economic cost of adapting or failing to change as the world warms, others are starting to fill the gap.

Policymakers will have to act fast if they do not want to see the result of failings in politically sensitive areas such as mortgages. A 2020 study of house prices in Florida by Benjamin Keys and Philip Mulde at the US National Bureau of Economic Research found that risk of rising sea levels had a significant impact on house prices in the state.

It is noticeable in the UK, too. Immediately after a property is severely flooded it loses around 20 per cent of its value compared to a similar, unflooded property, according to a study by Beltran-Hernandez and colleagues at the University of Birmingham. Any sharp, sudden drop in prices adds to the risk of homeowners being pushed into negative equity, where their mortgage is worth more than their property.

Beyond assets such as houses, the breadth of the economic hit that severe events such as flooding have might have to be reconsidered according to Simon Wren-Lewis, an emeritus professor of economics and a fellow at Merton College Oxford: “At the moment flooding is just treated as a supply shock, and because it normally only impacts a few regions it’s not a huge shock nationally. If they become more frequent then this may need to change.”

The bottom line is that not online the money invested in response to extreme weather will need to change, but also the government’s ability to tackle more frequent and complex emergencies, says Jill Rutter, senior fellow at the Institute for Government and former director at the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs.

In the wake of the flooding in 2007, then chief constable Tim Brain said: “In terms of scale, complexity and duration, this is simply the largest peacetime emergency we’ve seen.”

That means that the historical model of a severe flood followed by the environment agency lobbying for more cash can’t be sustained Rutter says. “It was often a case of waters flooding in first, then cash flooding in afterwards.”

Climate change adaptation will need the same cross-government emergency capabilities as pandemic response, Rutter says. “It’s yet another example of how important a new National Resilience Strategy is going to be.”

Despite its potential for disaster, adaptation is often just seen as an add on to net-zero efforts, with civil servants often expected to juggle both priorities with minimal resources.

“Adaptation is about avoiding something bad happening, so you can’t always see your success. Politically that can be a hard sell,” Brown says.

Sooner or later, however, the government will need to reconcile itself to more spending and put a number on the problem of climate adaptation. That will require a broader analysis that the calculations presently used for flooding because it will have to consider multiple weather events in quick succession.

According to a government spokesperson: “The government recognises the importance of protecting the nation’s natural environment and we are investing accordingly. Defra and its agencies received a £1bn increase in overall funding at the spending review so we can do more to tackle climate change and protect our environment for future generations.” These efforts include trying to shelter properties from coastal erosion.

With resources at present levels, “woefully short of what’s truly required” according to one senior official in the Environment Agency (and a second confirmed), “the economy and lives are on the line, as these events become more common”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments